Sleuthing the site of a century-old earthquake

The second-largest earthquake on the planet in 1904 happened somewhere in Alaska. It could have been St. Michael, Rampart, Fairbanks, Coldfoot or a place called Sunrise on the Kenai Peninsula. People felt the magnitude 7.3 at each place.

If an earthquake happens today, within a few minutes Alaska Earthquake Center researchers post a map with its latitude/longitude (the epicenter) and the depth of the rupture (the hypocenter). Historic earthquakes take a bit more detective work.

These earthquakes are worth knowing about because pinpointed locations tell scientists how busy a certain fault has been and hint at the possibility of future earthquakes.

That's why Carl Tape was so intrigued about an earthquake that happened when Teddy Roosevelt was on the campaign trail, Cy Young had just pitched the first perfect game and miners were sinking picks and shovels into creeks all over the American possession that was to become the territory of Alaska.

In 1904, scientists observing from afar figured the 7.3 earthquake could have been epicentered anywhere from northern Alaska to Canada's Queen Charlotte Islands. In the years following, scientists fine-tuned the earthquake's location, placing it closer to Fairbanks. But the focus was still fuzzy.

Tape chased down a more precise answer because a magnitude 7.3 is significant. In 2010, a 7.0 in Haiti killed more than 100,000 people and destroyed 250,000 buildings.

There are no surviving reports of anyone dying or of wrecked structures from the 1904 Alaska earthquake. In fact, there's not much information at all. The internet did not have much for Tape. With some good old library digging by archivists and help from others, he got to know more of the earthquake's character.

One good find was a diary entry from James Wickersham, who lived in what was then Alaska's largest city of Fairbanks as federal judge of a frontier legal district. Wickersham, the most reliable of recorders, wrote in pencil on Aug. 27, 1904: "Earthquake at . . . noon. From SW to NE and quite strong for several minutes — no damage but everybody ran outdoors."

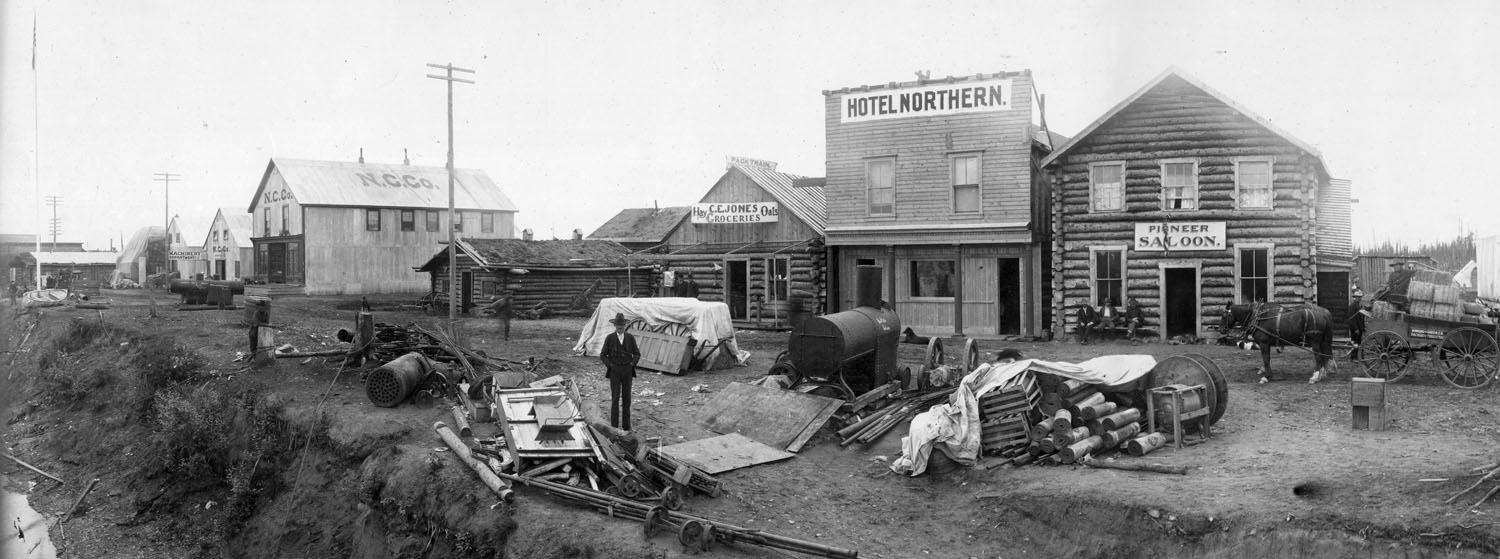

Tape, who grew up in Fairbanks, imagined the saloons he'd seen in black and white photos emptying on a hot summer day during one of the most widely felt seismic events in Alaska's history.

In time, more clues emerged. Like this line a scientist wrote on Aug. 27, 1904 at the Sitka seismic station, home of the only earthquake-measuring device in the state: "Both pointers went off the paper."

And this, from the Nome Semi-Weekly News of Aug. 30, 1904: "(St. Michael) was visited by a severe earthquake . . . lasting for more than five minutes. Everything was violently disturbed while the shocks lasted and a number of people were made seasick from the movements of the ground. Beyond the fear engendered in the hearts of everyone there was no damage done."

Using those reports, along with data from seismic stations outside Alaska and some computer modeling, Tape thinks the 1904 earthquake was centered just west of Lake Minchumina. Another large earthquake happened in 1935 along this weak spot in Earth's crust known as the Iditarod-Nixon fault.

Named in 1924 for the dying town of Iditarod on one end and the Nixon Fork of the Kuskokwim River on the other, the fault is a scar along the face of Alaska that runs southwest/northeast a few hundred miles.

The fault stretches from the village of Aniak up through and past McGrath. In early March, thousands of bootied dog feet in the Iditarod sled dog race will run across the straight line of the fault just after leaving Takotna on their way to the Iditarod checkpoint.

Outside of Aniak, McGrath and Takotna, few people now live along the Iditarod-Nixon Fault. In 1904, a few miners were probably standing in creeks along the fault, rattled by an earthquake almost lost in time.

Tape will present "The almost forgotten earthquake of the Alaska Gold Rush" as the first Science for Alaska lecture on Jan. 31 at 7 p.m. in the Raven Landing Center, 1222 Cowles Street in Fairbanks. His will be the first of six consecutive Tuesday lectures at Raven Landing, with subjects from Pluto to permafrost.