Ailing Ears Aloft

Northerners are an airborne lot. With few roads, lots of territory, and a long way to go from home to anywhere else on the globe, we have good reason to climb aboard airplanes at the drop of a ticket. That tendency to travel by air means that most of us are familiar with some annoying aspects of even the smoothest flight.

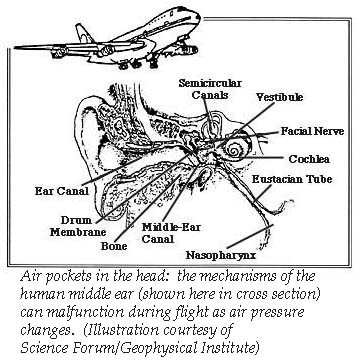

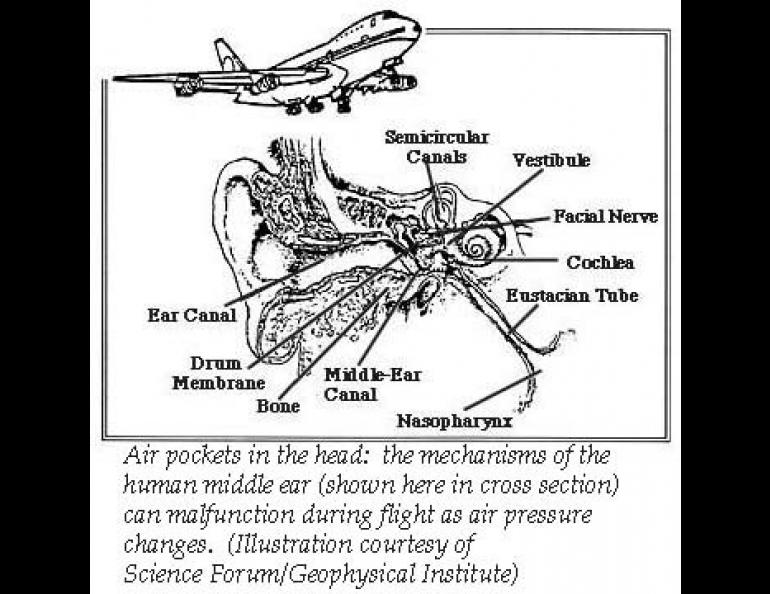

The most common problem is that our ears don't seem to want to leave home. Actually, the problem is in that portion called the middle ear--the eardrum, tiny bones, and spaces between the sound-catching equipment making up our outer ear and the nerve system of the inner ear that carries sound impulses to our brains for processing.

Because middle ear spaces contain air, the whole apparatus is sensitive to changes in air pressure. Even in a well-pressurized commercial jet, passengers can expect to adjust to an air pressure change equivalent to a fairly quick change in altitude of a few thousand feet. Human ears aren't really designed for that kind of abrupt adjustment.

To reach the middle ear, air comes in through the eustachian tube, a narrow passageway leading down to the back of the nose. By this rout, a little bubble of air makes its way into the middle ear every time you swallow.

Once within the middle ear spaces, the air diffuses out through the surrounding membranous lining. The air in-air out processes usually keep the pressure on both sides of the eardrum pretty well balanced. But problems can arise because the membranes keep absorbing the old air even if no new air is coming in through the eustachian tube. It may sound like a bad joke, but it really is possible to develop a partial vacuum in your head when your eustachian tubes are blocked.

The probability of having obstructed eustachian tubes is why experienced air travelers try to avoid flying when they have head colds. Anything impairing the air flow can lead at least to that woolly-headed feeling accompanying malfunctioning ears, at worst to an excruciating earache as the stressed eardrum is pulled toward the emptying middle ear.

Conversely, anything promoting air flow into the middle ear spaces can help prevent discomfort. Chewing gum or eating hard candy is useful because it encourages swallowing, and swallowing generates those helpful air bubbles in the eustachian tubes. A good broad jaw-popping yawn is even more effective, for yawning puts a stronger pull on the muscles opening the eustachian tubes than swallowing does. Sometimes nose-blowing helps, especially if you pinch your nostrils a bit to develop some back-pressure when you blow. When that works, it's because some air is forced through the closed-down tubes.

Should any of these techniques work for you in a plane going up, you may still have to apply another combination of them when the plane descends. As the plane rises, you encounter lower air pressure. There's less of a pressure difference across the eardrum, and the air within the middle ear expands in keeping with the lower pressure in the plane cabin. But a descending plane is carrying you back to higher air pressures, and a vacuum forms faster within the middle ear.

In my more cynical moments, I've though this pressure-susceptible arrangement of tubes and membranes is a cosmic conspiracy to keep Alaskans from traveling. At least, it can explain our seemingly earthbound ears.