Arctic Haze Comes of Age

Arctic haze has an innocuous-sounding name, but it isn't innocent stuff. It's air pollution. Affecting some 9 percent of the globe, it's the most extensive system of atmospheric fouling yet found.

In a peculiarly modern way, arctic haze has recently grown up: it's going to be the subject of a TV special. The staff of KUAC-TV, the University of Alaska Fairbanks public television station, has produced a program on the subject. Alaska viewers will see the show during November, and the Public Broadcasting System will offer it nationally in the spring.

The passage of arctic haze from discovery to the public eye might play on Mystery Theatre. It's a kind of detective story, with false leads, subtle clues, and much dogged legwork (or at least lab- and fieldwork). Thanks to fingerprinting--chemical fingerprinting--the trail even leads behind the old Iron Curtain.

Though arctic haze had been named and reported in 1957 by military weather observers, the report had been forgotten for a dozen years. Even its author, Murry Mitchell, Jr., thought he had come across an extraordinary event rather than a continuing problem. There was, after all, no local source of blowing dust or pollution in the high Arctic.

In 1972, another scientist went north for the air. Glenn Shaw, then newly appointed to the Geophysical Institute, wanted to measure the optical transparency of the atmosphere from Pt. Barrow. His aim was to find a baseline against which air at other locations could be compared; his expectation was that the clearest air in North America would be found above the pristine Arctic.

The reality was that the air was laden with particles. Its opacity was greater than that of the air over Arizona, dusty country where Shaw had worked previously.

When Shaw discussed his findings with colleagues, he met disbelief. People were so committed to the idea of the untouched Arctic that he kept receiving sincere advice on ways he might correct his techniques, his instruments, and therefore his results.

But more work, by Shaw and others, confirmed the findings. Something was there, and it was there in quantities substantial enough to reduce the springtime solar radiation reaching the ground at noon by 30 percent. Haze bands could extend for hundreds of kilometers. Their cause was a puzzle. Thin clouds and local sources of pollution or windblown dust were quickly eliminated. The airborne particles had to be coming from somewhere else.

At a conference in the mid-1970s, Shaw caught the ear of atmospheric chemist Kenneth Rahn, a faculty member at the University of Rhode Island. Rahn was fascinated by the problem of deciphering the nature and sources of arctic haze. In April 1976, he joined Shaw in a series of airborne aerosol collection experiments near Barrow.

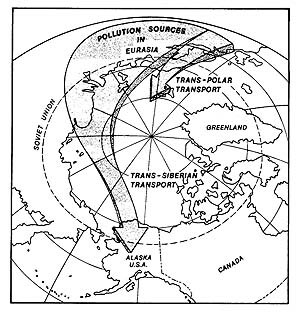

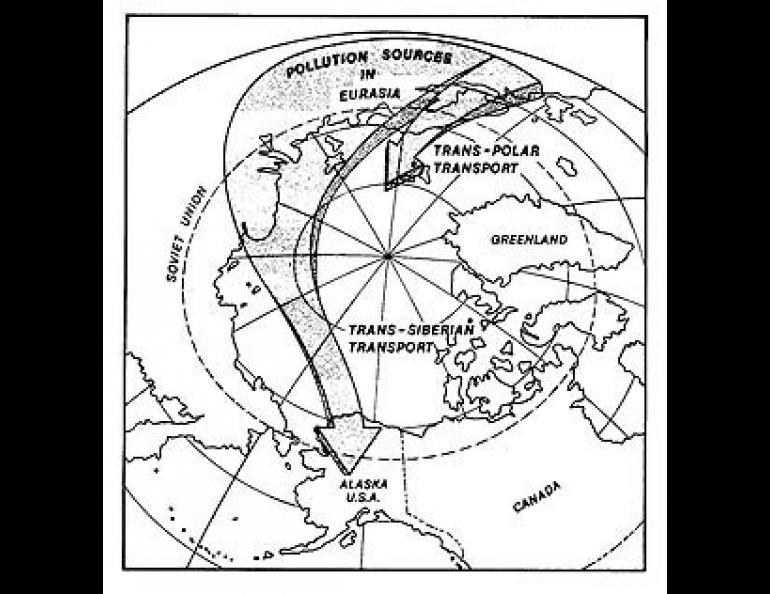

Analysis of the collected particles gave a clear-cut result: arctic haze was dust from the earth's surface, probably from dust storms. Rahn pursued meteorological information, and found that air masses had been moving into Alaska from Asia at the time the collecting aircraft had flown. The moving air had caused sandstorms in the Gobi and Takla Makan deserts; in fact, the atmospheric systems had dumped heavy falls of yellow sand on Nagasaki in Japan.

Apparently the culprit was identified , yet some nagging doubts remained. Sandstorms blew sporadically in Asia, yet arctic haze was regularly present all winter and through the early spring. Pilots for the Scandinavian Airlines System, entertained by the thought of supporting science during the long and generally boring flight over the pole, had been taking photos for Shaw to document where and when arctic haze appeared along the route. They found it at times and in places that could not be correlated with Asian sandstorms.

Monitoring stations on the ground at Barrow kept filtering air, and the particles trapped were not bits of the Gobi desert. Mostly, they were sooty specks. Slowly, evidence built. New and exquisitely sensitive technologies permitted Shaw, Rahn, and their students to analyze the composition of haze particles and even the attendant gases--a process known as chemical fingerprinting, appropriately for the detective metaphor. The Gobi fallout had been a fluke. They found that the haze was mainly industrial pollution, and--because of the nature of the traces of fuels entrained in the haze--it wasn't coming from North America.

That North America wasn't the source for arctic haze was confirmed by measurements and analysis of air samples collected by well-instrumented aircraft flown over the Alaska and Scandinavian sectors of the Arctic during the 1980s. (This set of experiments, the Arctic Gas and Aerosol Sampling Program, is known by its wry acronym--AGASP.) A definitive clue was what wasn't there: the high-tech industries in the U.S. and Canada exhale certain solvents and fire extinguisher compounds not used in Europe.

Much is now known about arctic haze. Its source is the smokestacks of Europe and the Soviet Union. It builds slowly throughout the winter, trapped in a stable arctic airshed like sewage in a stagnant pond. It peaks in April but has vanished by late May, washed from the air by spring precipitation and swept away by changing air movements. While it is there, this swath of scummy air is regrettable proof that we all share one planet: the Arctic too is touched by human activity, even when it takes places thousands of miles away.