Arctic haze makes its spring appearance

While looking out the window on a flight to Kotzebue on a recent spring day, I saw two dark bands hanging in the air above the Brooks Range. A day later, while on the ground, I noticed the mountains were pinkish rather than white. The tint looked like something you might see in Denver, where car exhaust fuzzes up the view, but I was in the Arctic, a land of few cars.

I was probably seeing arctic haze, said Glenn Shaw, an atmospheric scientist and professor emeritus at UAF’s Geophysical Institute. Arctic haze shows up in varying levels every spring in northern Alaska and elsewhere at the top of the world.

Shaw was one of several scientists who sampled the haze in the 1970s to find where it came from. They found that sulfur compounds and black carbon particles—the products of iron, nickel and copper smelters and inefficient coal-burning plants—made up a large proportion of arctic haze. Later studies showed much of the pollution was coming from the former Soviet Union and other areas of Eurasia.

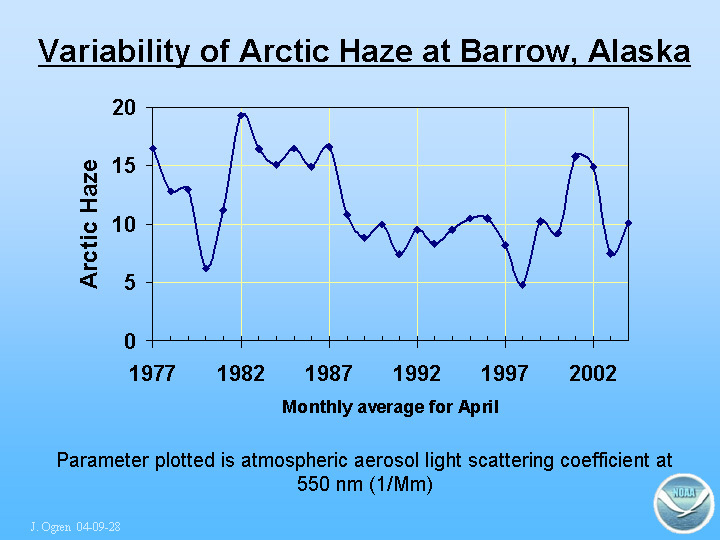

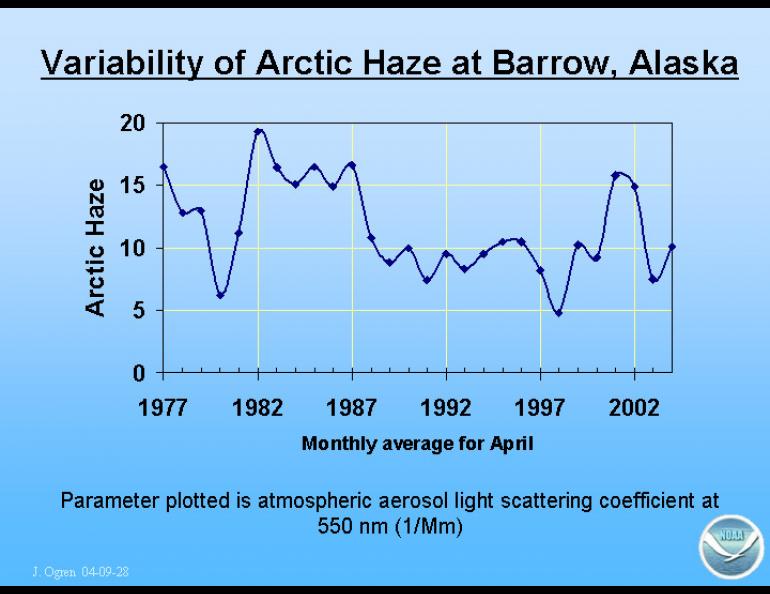

Measurements from Barrow show that arctic haze decreased from the 1980s to the 1990s, but has wavered in recent years. Some scientists thought the decrease might have been due to the breakup of the Soviet Union and less operation of factories there. Other scientists point out that the presence of arctic haze also depends on shifting weather patterns that might bring the polluted air to Alaska in greater quantities in some years.

“I think (the fluctuation of arctic haze at Barrow) is a mix of both,” said Betsy Andrews, a research scientist at the University of Colorado at Boulder. Andrews studies airborne particles at NOAA monitoring stations including Barrow and a few other remote places, such as the South Pole, Mauna Loa in Hawaii, and the island nation of Samoa in the South Pacific. Andrews and her colleagues also make measurements in central Illinois and Oklahoma.

Arctic haze shows up at the Barrow site each year from December to May, Andrews said, and its presence makes Barrow’s air less clean than the other remote stations, especially the one at the South Pole.

“South Pole’s just amazingly remote,” Andrews said over the phone from Boulder. “It’s a really clean place.”

Even with the spring visit of arctic haze, Barrow has clean air when compared to stations in the Lower 48 that Andrews and others monitor, such as one in Bondville, Illinois, which is located among farm fields in the central part of the state.

“Barrow’s high reading for aerosols is lower than Bondville’s low about 95 percent of the time,” Andrews said.

The air sampled at the Barrow observatory, about five miles east of town, carries little trace of arctic haze in the summer, Andrews said.

“The air in summer is coming more from over the clean Arctic Ocean,” she said. “We see a lot more sea salt in Barrow’s air in summer.”

Dust from Asian deserts is another particulate that researchers have detected in Barrow’s air in recent years. Dust liberated by windstorms in the Gobi Desert and other areas doesn’t make it to Barrow every year, but researchers have found it showing up more now than it did in the past.

“In the 80s, Barrow might get one dust event per year, but recently, there’s been three or four per year, mostly in March and April.”

More Asian dust in the air is possibly the result of more severe storms, more Asian soil being tilled, or a combination of both. And the dust is traveling all over North America. As Andrews spoke to me on the phone, she noticed a story in the Denver Post web edition. One of her colleagues had identified what was causing a whitish haze over the Front Range of the Rockies—Asian dust.