Arctic Mirage (Hillingar)

Just as cold snow differs from hot sand, arctic mirages differ from those of desert regions.

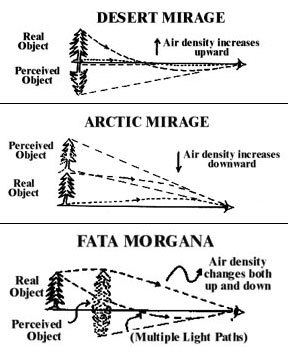

Desert mirages result from the heating of air overlying a warm surface; the hot sand. In a desert mirage objects appear to be lower than they actually are. Also, the image is inverted top for bottom.

Just the opposite happens in an arctic mirage because it results from the existence of relatively cold air next to the ground surface. That cold layer exists because the cold snow, ice or water surface extracts heat from the air just above. In the arctic mirage a distant object appears right way up but higher up than the actual location.

Though arctic and desert mirages seem to be quite different, they share a common fundamental cause. It is that light rays passing from an object through air to an observer always refract (bend) in the direction of increasing air density.

In a "normal" atmosphere, air is less dense the higher up above the earth's surface. Consequently, light rays traveling horizontally over the earth's surface actually bend downward as though trying to follow the curved surface. For this reason one sees distant mountains that actually are below the horizon that one would see if light truly traveled in straight lines in the atmosphere.

If the earth's surface is hot, it heats the air just above, making the air there less dense than air higher up. Consequently light rays traversing such a region bend upward causing false lakes and inverted mountains to appear just above the apparent ground surface. These images tend to dance or otherwise change rapidly since dense air above lighter air is too unstable to remain static.

Contrasting with this instability is the steadiness of an air mass which is coldest at the bottom, the condition creating the arctic mirage. Especially over cold ocean areas, the air density can change with altitude so rapidly that the horizon appears to lift up like the edges of a saucer. Coastlines normally well below the horizon are raised up into view.

Early Norsemen called these mirages hillingars. The hillingar effect may well have contributed to the Norse discoveries of Iceland and Greenland, according to the suggestion of H.L. Sawatzky and W. H. Lehn, writing in the June 25, 1976 issue of Science magazine.

The hillingar even has an Alaskan connection in the form of a lodging house, the Captain Bartlett Inn in Fairbanks. The inn is named after Captain John Bartlett who seems to hold the distance record for seeing objects below the horizon with the aid of the hillingar effect. His ship, the Effie. N. Morrissey, was located more than 500 km (300 miles) away from Iceland one day in 1939 when Captain Bartlett spotted one of the Icelandic mountains.

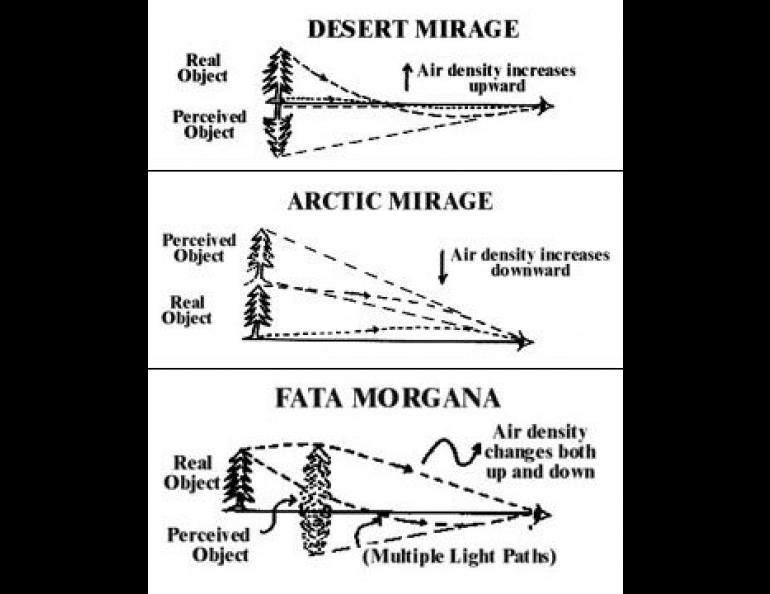

Sometimes, complex mirages called fate morganas are seen in conditions transitional between those favorable for desert mirages and arctic mirages. The fate morgana mirage may consist of a double image of an object, one image inverted, the other right side up. These appear frequently in broad valleys such as Alaska's Tanana Valley where temperature inversions and complex air layering are common.