Arctic Plants Controlling Own Nitrogen Destiny

Arctic plants, long thought to be the slaves of tiny creatures in the soil that dole out nutrients at a sluggish pace, may be in control of their own destinies. That's the thought of one researcher, who thinks northern plants might take a shortcut to absorb precious nitrogen.

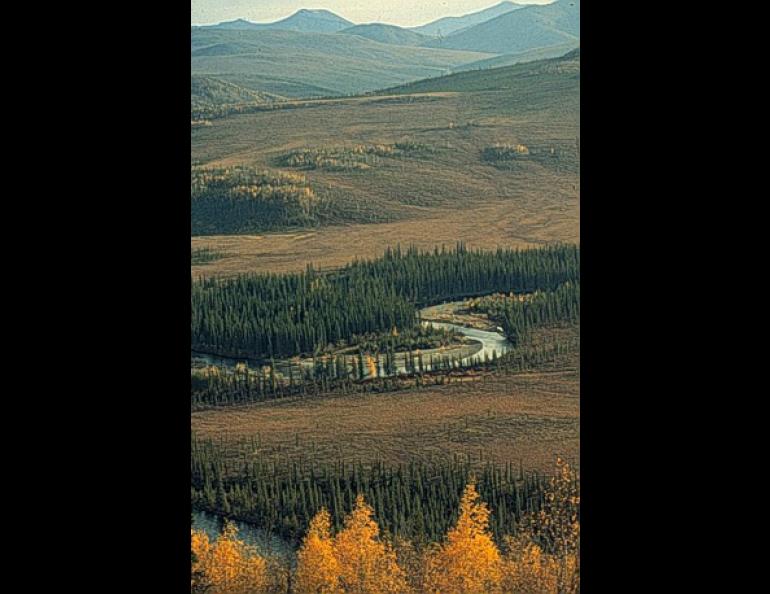

Knut Kielland is an ecologist who has spent countless hours kneeling on tundra in windy, buggy places, such as Toolik Lake on Alaska's north slope. An associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Kielland has so admired the mettle of dwarf willows, cottongrass, and other arctic plants that he set up experiments to determine how the plants were getting enough nitrogen to survive.

Nitrogen molecules make up about 75 percent of the air we breathe. The colorless, odorless gas passes through human lungs without much effect, but nitrogen means almost everything to plants. Most plants take up nitrogen from the soil and convert it to living cells and tissues. Outside the tropics, almost all of the plants on Earth could grow faster if they had more nitrogen.

Plants get their nitrogen fix through the work of soil microbes, the smallest forms of life on Earth. Soil microbes, including bacteria and fungi, process organic matter in the soil, everything from fallen leaves to dead animals. The microbes convert the dead stuff into inorganic nitrogen, such as ammonium and nitrate, which plants suck up through roots. For more than 100 years, scientists have thought plants could only use this form of inorganic nitrogen, which microbes have converted from bulky organic molecules. Kielland thinks northern plants are less passive.

"The notion that plants are merely dumb vegetables sitting there at the mercy of microbial activity needs to be reevaluated," he said. Cold soils in the north slow microbes to a crawl, limiting the nitrogen available to plants and allowing organic matter to build up year after year. Peat layers in some North Slope soil contain the remains of plants that have been dead for thousands of years. The far-north system of nitrogen turnover is so slow that Kielland wanted to check out if the conventional nitrogen cycle was providing northern plants what they needed.

Kielland found that microbes in the soil supplied the plants with only about half the nitrogen they needed. This made him think plants were gathering some of their nitrogen from another source-amino acids in the soil. Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins released from dead organic matter in the soil. Northern plants may be able to absorb amino acids from the soil, short-circuiting the conventional path of the nitrogen cycle. For years, researchers have thought microbes had to absorb amino acids and excrete the nitrogen before plants could use it.

To see how fast northern plants process nitrogen, Kielland and his colleagues injected amino acids labeled with stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen into northern soils. By following the fate of these labeled materials, they found the plants absorbed the amino acids directly.

The plants' fondness for nitrogen in the form of amino acids tells Kielland that the conventional theory of the nitrogen cycle may need a little tuning, as do computer models that rely on the old hypothesis. "Plants are much more proactive and in control of their nitrogen uptake," he said. "It's not just the bugs in the soil calling the shots."