Bar-tailed godwit goes the distance

On the evening of Oct. 7, 2007, a female bar-tailed godwit leapt off a mud flat at the mouth of the Kuskokwim River. The bird might not touch the ground again until it reaches New Zealand, more than 7,000 miles away.

Bob Gill, a biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage, saw on his computer that the bird had taken flight on its fall migration from Alaska to New Zealand. A few weeks earlier, Gill and his colleagues had tracked another female godwit on a flight to New Zealand. They found that the bird remained in the air for eight straight days.

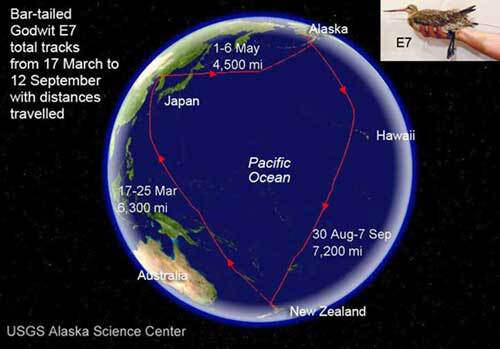

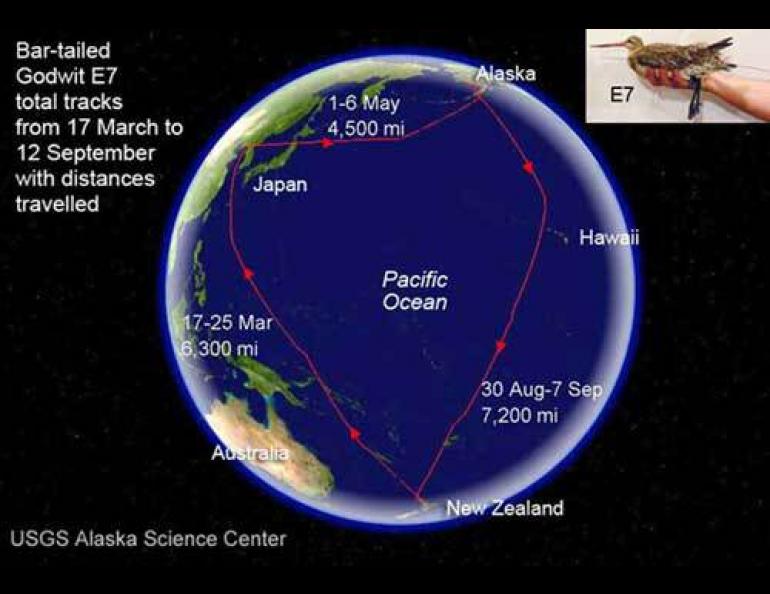

On Aug. 29, that bird, called E7 for a tag on its upper leg, took off from the Yukon River Delta. Biologists tracked it as it flew to North Cape, New Zealand and landed on Sept. 7. Gill knows the bird didn’t land on the journey because of its constant movement as he and others tracked it.

Biologists in New Zealand captured E7 in February and implanted a transmitter in its abdomen. That satellite transmitter showed that the godwit left New Zealand in mid-March and flew nonstop to China, a continuous flight of 6,300 miles that took eight days. The bird remained there for five weeks before taking off for its breeding grounds in Alaska.

On May 2, the godwit left China and headed out over the Sea of Japan and the North Pacific, taking six days to reach the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta. This flight, also nonstop, covered 4,500 miles. The bird summered in Alaska; where it fattened up on marine worms and thumbnail-size clams that it plucked from the mud with its long beak.

After a summer of breeding and feeding on Alaska’s riches, the godwit known as E7 began a 7,200-mile nonstop flight to New Zealand, the equivalent of a flight from San Francisco to New York, and then back to San Francisco again. Only the Concorde-shaped godwit never stopped to refuel. And pausing on the ocean wouldn’t do a godwit much good anyway—adapted to life on the shore, the birds can’t feed on the water, or swim for a long time.

Gill thinks the birds have somehow evolved to be avian meteorologists, with the ability to sense upcoming storm systems that give them tailwinds for much of the journey (E7 cooked out of Alaska at 60 mph, but sometimes slowed to 35 mph in areas with low winds).

Gill and other researchers also have noted that the birds’ bodies start changing in anticipation of the great storms that help them southward.

“They shrink their digestive machinery—their gizzards and intestines get smaller—prior to flight,” Gill said.

During E7’s flight from Alaska, the bird headed for Hawaii, then turned southwest toward Fiji before heading south to New Zealand. Along the way, flying at altitudes as high as 15,000 feet, the bird lost 50 percent of its body weight, and may have shut off half its brain to nap along the way, an ability researchers have noted in mallard ducks.

How E7 and other godwits find their way from Alaska to the tip of New Zealand is a mystery to scientists. Birds will often zigzag down, following weather patterns, but “once they’re into the Tropics, it’s mostly straight to New Zealand,” Gill said.

Not all bar-tailed godwits make the nonstop flight. A few tagged birds have run into headwinds in the second half of their journey and have touched down before reaching their destination, Gill said.

If the battery on its transmitter survives, the godwit that left the Kuskokwim on Oct. 7 may allow scientists to find that it also will keep beating its wings over the sea until it reaches New Zealand around Oct. 15, when it will finish a silent, incredible journey.

“I’ve been studying them 20 years and it’s still jaw-dropping to me,” Gill said.