Cracking Logs and Warped Boards

Logs crack, most often in long spirals. Boards curl. Doors stick in damp weather, and chairs pull apart when it's dry. Wood is a marvelous material in many ways, but it does have its problems under changing humidity conditions.

The original function of wood, of course, was to hold up trees, not houses. Wood that is supporting a living, healthy tree is not subject to large, uncontrolled humidity changes. The inner part of the trunk is shielded from fluctuations by the outer part, which is carrying moisture between the leaves and the roots of the tree. Food travels in the living phloem tissue just under the bark. Water and minerals are carried through the xylem, the living but no longer growing outer part of the woody trunk.

When the tree dies or is cut, it dries until its moisture content is in balance with the humidity of the surrounding air. As water is removed from the xylem tissue, it shrinks. But the shrinkage is not uniform. The cells of the xylem have the dual job of transporting fluids along the tree and resisting bending. Understandably, the structure and consequently the amount of shrinkage differ in the direction up and down along the tree trunk, the radial direction (from the center to the bark), and the tangential direction (around the tree). Furthermore, unless the drying is carefully controlled, the outer part of the wood will dry faster than the inside. All of this puts stresses on the drying wood.

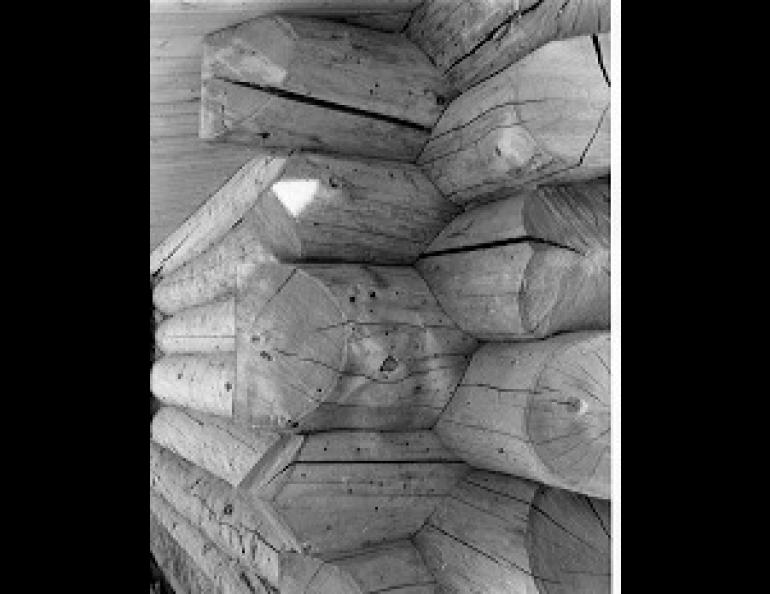

Shrinkage along the grain of the wood is very slight -- generally less than a tenth of a percent. Tangential and radial shrinkages are much larger. Worse, they are often quite different. In a spruce log, for instance, the radial shrinkage on complete drying is about three percent, while the tangential shrinkage is more than twice that much. The circumference of a circle is an exact multiple of its radius, so if the fractional shrinkage of the circumference is more than that of the radius, something gives, and the circumference develops gaps. If we apply this to house logs, where the situation is made worse by the outside of the log drying faster than the inside, the result is cracks.

Cut boards have slightly different problems. A board which is cut so that the growth rings, looked at from the end of the board, show as little curvature as possible is unlikely to warp if the drying process is properly controlled. However, if a board is cut nearly parallel to the bark, so that the growth rings appear to curve on the board end, the differential shrinkage on drying will have the same effect as if the growth rings were shrinking rubber bands. The growth rings will try to straighten out, and the board will tend to curl in the opposite direction from the curve of the growth rings. Knots will also cause problems, as their diameters will shrink more than will the surrounding wood, which is oriented so that shrinkage is in the tangential and lengthwise directions.

Regardless of how well the wood is cut, lumber will expand and contract to some extent as the humidity changes. A wooden door that is properly fitted in low humidity will expand and stick in very wet weather. If it is properly fitted in wet weather, it may develop gaps when the weather is very dry. Furniture to be used in an area where the indoor climate is dry should be assembled under similarly dry conditions, or joints may loosen in use.