Cufflinks in the Sky

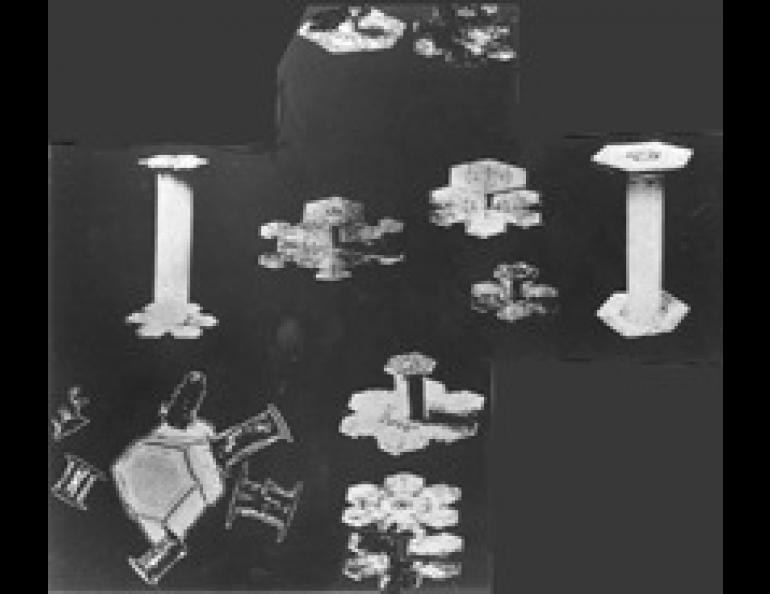

One of the most intriguing of the many forms snowflakes can assume is the "cufflink" crystal. The first photo I ever saw of these, in a very old children's book, described them as rare cufflink crystals, from a great storm that struck New England. Like wolves, they may be rare in New England, but not in Alaska. They are, however, very small. A sixteenth of an inch across is a large one, and that would hardly make a sizable cufflink for a Lilliputian.

How could such a shape, technically a capped column, form? Ice crystals are basically hexagonal prisms, like a section of pencil cut square on both ends. Their mode of growth is controlled by moisture and temperature. At low humidities, the faces of a crystal grow fairly evenly. As the humidity rises, first the edges and then the corners begin to grow faster than the rest of the crystal. Temperature controls whether the crystal grows lengthwise, making a shape like a long pencil, or sideways, making a flat, hexagonal plate. At temperatures from 15 degrees F to -10 degrees F , the plate form dominates. At higher temperatures needles and columns predominate; at lower temperatures columns are most common.

Now imagine an ice crystal growing at low temperature and low humidity in the upper part of a cloud. The crystal will grow as a tiny column, probably somewhat longer than it is wide. Because the conditions favoring this shape may prevail over a deep layer of air in Alaska (especially north of the Alaska Range), the crystal may grow to an appreciable size before it falls all the way through the layer -- perhaps a thirty-second of an inch in diameter. Then the crystal falls into a warmer, slightly wetter region of cloud. Edge growth and the flat plate shape now predominate, and the crystal will begin to grow plate-like extensions from the edges of its end faces. A capped column has been produced.

These fascinating crystals are not often recognized, because of their small size. It takes good eyes to notice that a speck of powder snow has such an interesting shape. A small hand lens, however, will allow you to see the intricate detail of their structure. They are commonest in fine, dry, powdery snow, accompanied by small plates and minute assemblages of plates and columns. Take a magnifying glass outside the next time it snows, catch a collection of snowflakes on your sleeve, and enjoy the complexity of snow!