Dale Guthrie opened door to lost world

Sometimes — but not very often — a door creaks open to a lost world. Sometimes the right person steps in.

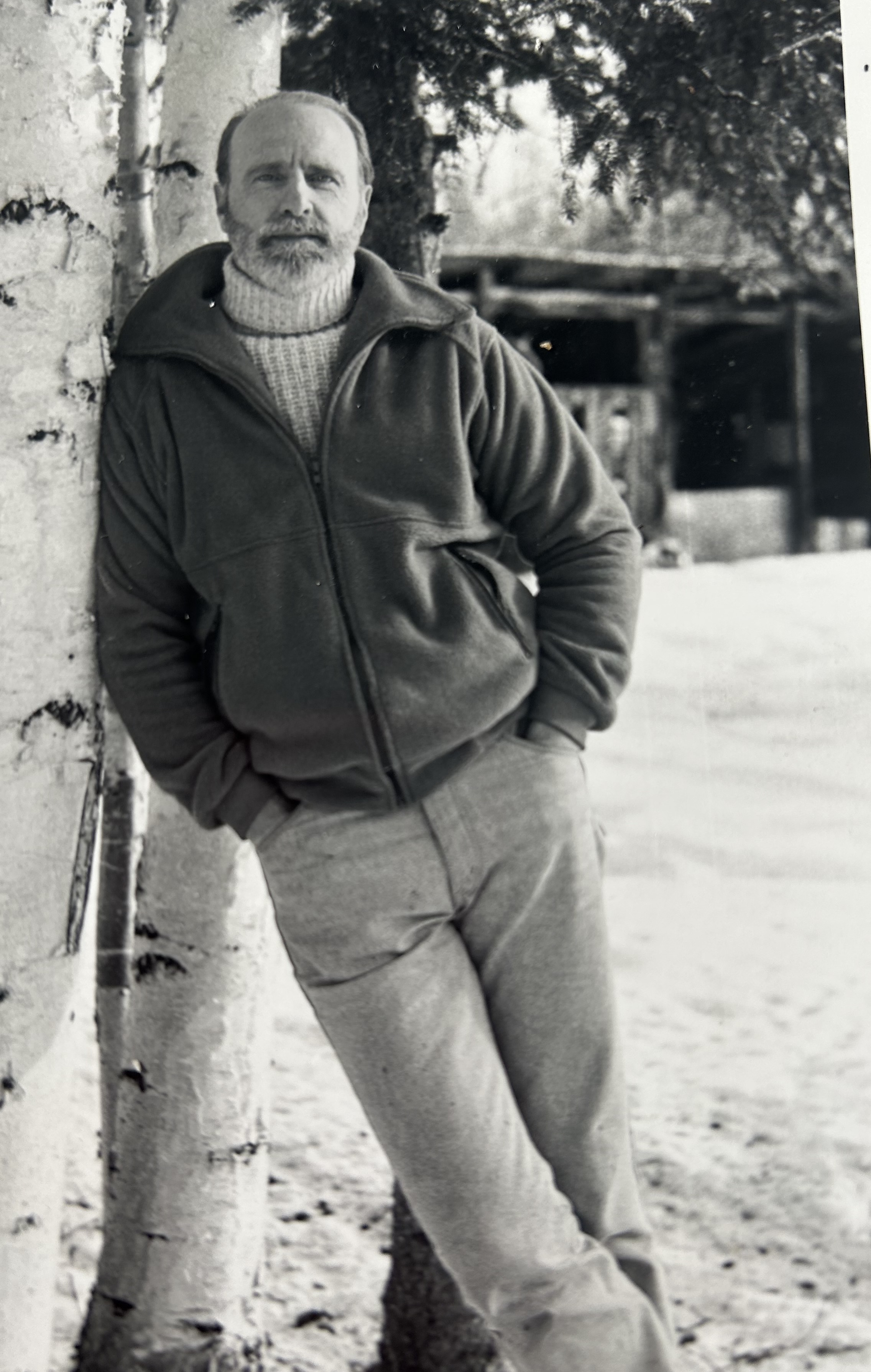

Dale Guthrie, an Alaska biologist and paleontologist who died in 2024 at the age of 88, was that guy.

In summer 1979, Guthrie responded to the report of a frozen creature emerging from the thawing exposure of a Fairbanks placer gold mine. That discovery, and his ability to weave scattered details into a coherent whole, expanded what we know about ice-age Alaska, the Bering Land Bridge, and cave art throughout the world.

At the time of the discovery of “Blue Babe,” a 50,000-year-old extinct steppe bison, Guthrie had been a researcher and lecturer at the University of Alaska Fairbanks since 1963. He had 15 years of familiarity with late Pleistocene fossils that gold miners often uncovered.

Steppe bison, ancestors of today’s plains bison, once roamed the former grasslands from Spain over the Bering Land Bridge all the way to Texas.

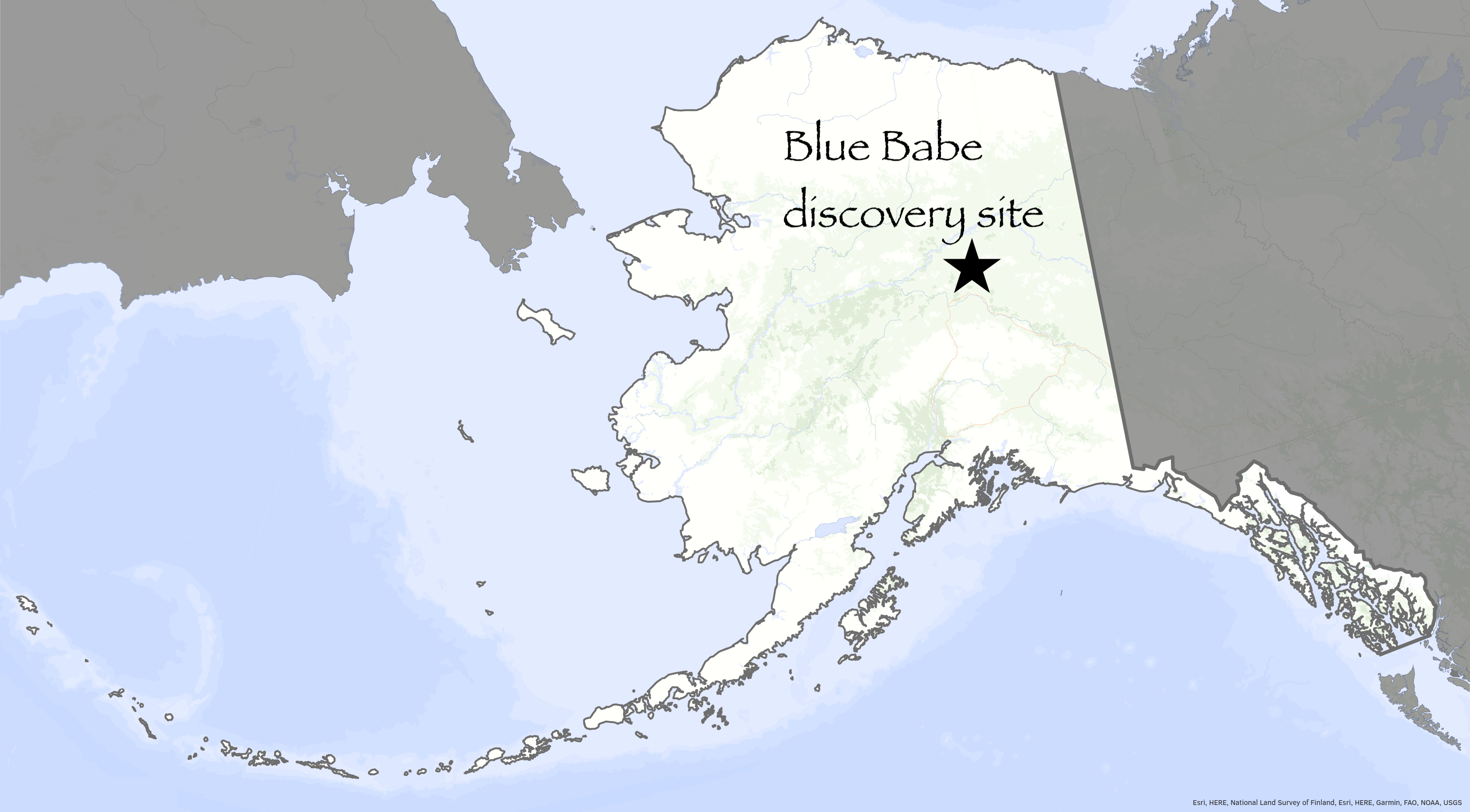

After hearing of a pair of cloven feet protruding from a mass of frozen soil, Guthrie drove an hour on gravel roads north of Fairbanks. He arrived at the mine of Walter Roman.

Roman pointed to the body parts extending from the frozen ground that resembled a dirty glacier. Guthrie noticed red muscle tissue clinging to the bones, along with some black hair.

“Mr. Roman’s find was a first for the both of us,” Guthrie wrote in his book “Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe.” “He had found a true mummy, and it was a rare event.”

The timing of that rare event was not perfect for Guthrie. He was preparing for a year’s sabbatical from his position at UAF.

However, realizing what a unique find the frozen steppe bison was — and that he didn’t have much time before flies would lay eggs on its Pleistocene flesh — Guthrie pivoted.

He enlisted his wife Mary Lee and his son Owen to help him excavate the animal while Roman paused work on that section of the mine. Guthrie remembered the scent of the permafrost-preserved creature as they worked on those long midsummer evenings 46 years ago.

“A rich, pungent rottenness, like nothing else I have smelled, filled the air. It was a rottenness aged for millennia in the frost — not a stench, but a sweet, intense tang.”

The Guthries recovered the steppe bison — nicknamed “Blue Babe” in part because of a mineral that had dusted the animal’s hide blue — and the soil that surrounded it. They secured the bison in a freezer at the university’s Institute of Arctic Biology.

Dale and Mary Lee then flew off on an altered sabbatical.

Newly fascinated with the life history of a specific creature gone for thousands of years, the couple visited zoos, museums and caves in Europe and the Soviet Union.

In the zoos they saw a much smaller species of European bison that could be the closest living relative to the steppe bison. They dropped in on colleagues who worked on mummies of Pleistocene animals. In France, they climbed into caves to see paintings by people 30,000 years ago.

Visits to the caves and a decade of further ruminations resulted in Guthrie’s 502-page book, “The Nature of Paleolithic Art.” In that work, he reimagined who might have been the artists etching images of bison, mammoth and women onto cave walls.

“I would argue that the crowning achievement of (Guthrie’s) entire career is ‘The Nature of Paleolithic Art,’” said Dave Norton, a retired UAF scientist and Guthrie’s friend. “Not only does it scuttle generations of speculation about the spirituality and supposed deism motivating the artists, it reveals the artists to be apprentice-hunters, overwhelmingly adolescent males.”

From thinking about the animals once living here and the plants that sustained them, Guthrie developed a notion that the Bering Land Bridge was cloudier and wetter than the dry grasslands that extended on both sides of it into Asia and North America.

He suggested that warm, swampy conditions on the land bridge prevented large mammals like the woolly rhino from migrating into the New World, and discouraged American species like the giant, short-faced bear from crossing the bridge in the other direction.

Fifty years later, computer climate models and researchers pulling cores from the floor of the Bering Sea agree with his thoughts of what the northern world was like way back then.

His wife Mary Lee gave examples of how Guthrie immersed himself in learning.

“To better understand hunting tools, he made a microblade point — then used it in the backyard,” she said. “At the Dry Creek archaeological dig with Roger Powers, he brought a pig down to the camp and the students used stone flakes to butcher the pig before cooking it on the fire.”

Guthrie was a painter, sculptor, bowhunter, teacher and uncommonly deep thinker, said those who knew and admired him.

“Dale has had an outsized influence on all of us in the paleoecology business,” said UAF’s Nancy Bigelow, an expert on landscape and vegetation changes in Alaska’s past. “All of us paleoecologists have used Dale’s work to frame our own models of what the Interior was like during the last ice age.”

“He saw things as whole, not as the subdisciplines that scientists typically divide the world into,” said Dan Mann, a UAF scientist with a similar depth of interest in ice-age Alaska. “He was one of those rare people who could go from details to wholes, and then back again.

“The passing of such a unique and powerful intellect leaves a gap that I doubt will ever be filled in the Alaska pantheon of scientist-naturalists,” Mann said.