The Days of the Mammoth Steppe in Alaska

Eighteen-thousand years ago, while New York and Chicago were silent under tons of glacial ice, the grasslands of Alaska echoed with the roar of the American lion. In those days, a vast, dry belt wrapped the northern part of the globe, providing a home for lions, bison, and woolly mammoths. Stretching from France to Whitehorse, the only apparent interruption in that belt was near Alaska.

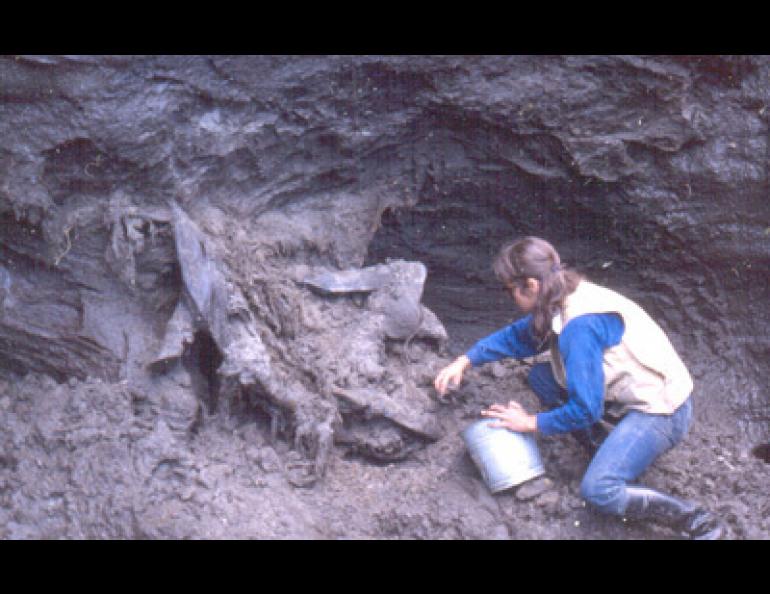

Dale Guthrie has spent much of his professional life studying the animals that lived in that ice-free zone, also known as the Mammoth Steppe. Guthrie is a retired biology professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. In the late 1970s, Guthrie excavated and preserved a 36,000-year-old bison from Walter Roman's Fairbanks mining claim. That bison, known as Blue Babe, is now one of the star attractions of the University of Alaska Museum.

The Mammoth Steppe that stretched over the northern part of the globe was dry, cold, and rich with grasses, sedges, forbs and sages. According to fossils found in Europe, Siberia, and Alaska, this landscape supported a curious mix of large animals, including rhinos, bison, lions, reindeer, and muskoxen. Guthrie compares the Mammoth Steppe of the ancient northland to shortgrass prairies that exist today near Minot, North Dakota, and northern Montana.

The Mammoth Steppe was so dry that few lakes existed and rivers were more like streams. Perhaps the only variation in the climate of the Mammoth Steppe was on the Bering Land Bridgethe area where scientists say western Alaska and eastern Russia were connected when sea level was lower thousands of years ago. That swath of land that connected the Old and New worlds was perhaps 500 miles wide, Guthrie said, much more narrow than the continents to the east and west where the bulk of the Mammoth Steppe existed. Bordered by ocean on two sides, the Bering Land Bridge may have been cloudier and wetter than most of the Mammoth Steppe, factors that may have interrupted a few species of animals and plants from migrating east or west, Guthrie said.

Guthrie calls this area the "buckle" on the belt of the Mammoth Steppe that may have prevented some Old World species from crossing to the New World, and vice versa. Other researchers found that regions near what is now Bering Strait were moister and included more tundra vegetation than areas farther east.

Few animals can survive eating tundra plants, and Guthrie said the Bering Land Bridge probably had a mix of tundra and grasses, enough to allow many species, such as the saiga antelope and woolly mammoth, to thrive. But the mix of tundra may have been too much for other species that depended on dry-loving plants. Those animals included the woolly rhino, the remains of which have been found at the headwaters of Russia's Anadyr River but not farther east. Animals whose fossils are found in Alaska but not in Russia include American camels, giant short-faced bears, giant muskoxen, and badgers. Other scientists have found that weevils and ground beetles adapted to the Mammoth Steppe in Asia have eastern ranges that stop at the land bridge.

Lions, bison, mammoths and other creatures of the Mammoth Steppe roamed Alaska until the landscape began to change about 13,000 years ago, and the dry plants gave way to birch, poplar, and other trees. Soon to follow the exotic animals were even stranger creatures from the east, the first humans to cross the Bering Land Bridge.