Denali Fault Earthquake a Once-in-a-Lifetime Event

Many Alaskans now have a vivid memory of where they were on Sunday, Nov. 3, when the world's largest earthquake so far in 2002 rocked the state. Many Alaska scientists will remember the weeks after as a blur of activity.

One week after the earthquake, I dropped in on seismologists at the Alaska Earthquake Information Center on the third floor of the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. A half dozen of them sat around a long table, looking weathered after a mission to install portable seismometers just off the roadways slashed by the rupture of the Denali Fault. The seismometers are measuring the hundreds of aftershocks that have followed the earthquake.

The scientists returned with tales from the roadabout fractures in the ground that offset lines on the highways by as much as 22 feet, about a store owner on the Tok Cutoff Road who said his business was down about 50 percent because people were either leaving the area or holing up after the earthquake.

After the seismologists finished briefing State Seismologist Roger Hansen, he thanked them for a job well done. Just down the hall, Geophysical Institute Associate Professor Jeff Freymueller was waiting for a phone call from a Science News reporter who was writing a story on the earthquake. Freymueller uses global positioning system receivers to detect Earth movement; when I visited, he had a crew of people installing receivers off the Parks, Richardson, and Alaska highways.

This earthquake is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, he said. Its bigger than the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, and roads cross the fault in three places.

With the GPS antennas, Freymueller and his colleagues will measure how much the ground surface is moving after the earthquake, which will tell them something about Earths upper mantle, a place about 30 kilometers (18.6 miles) beneath the ground surface where the rock is so hot it behaves like a fluid.

The Denali Fault earthquake may be a once-in-every-1,000-years event, Freymueller said.

Post-doctoral Fellow Hilary Fletcher of the Geophysical Institute had made GPS measurements along the fault before the earthquake. She found the fault was slipping about 7 millimeters per year where it crosses the Richardson Highway and about 11 millimeters per year at its intersection with the Parks Highway. Based on the 8 meters (about 24 feet) of ground offset the earthquake left behind in places, Freymueller calculated that the strain had been building for about 1,000 years.

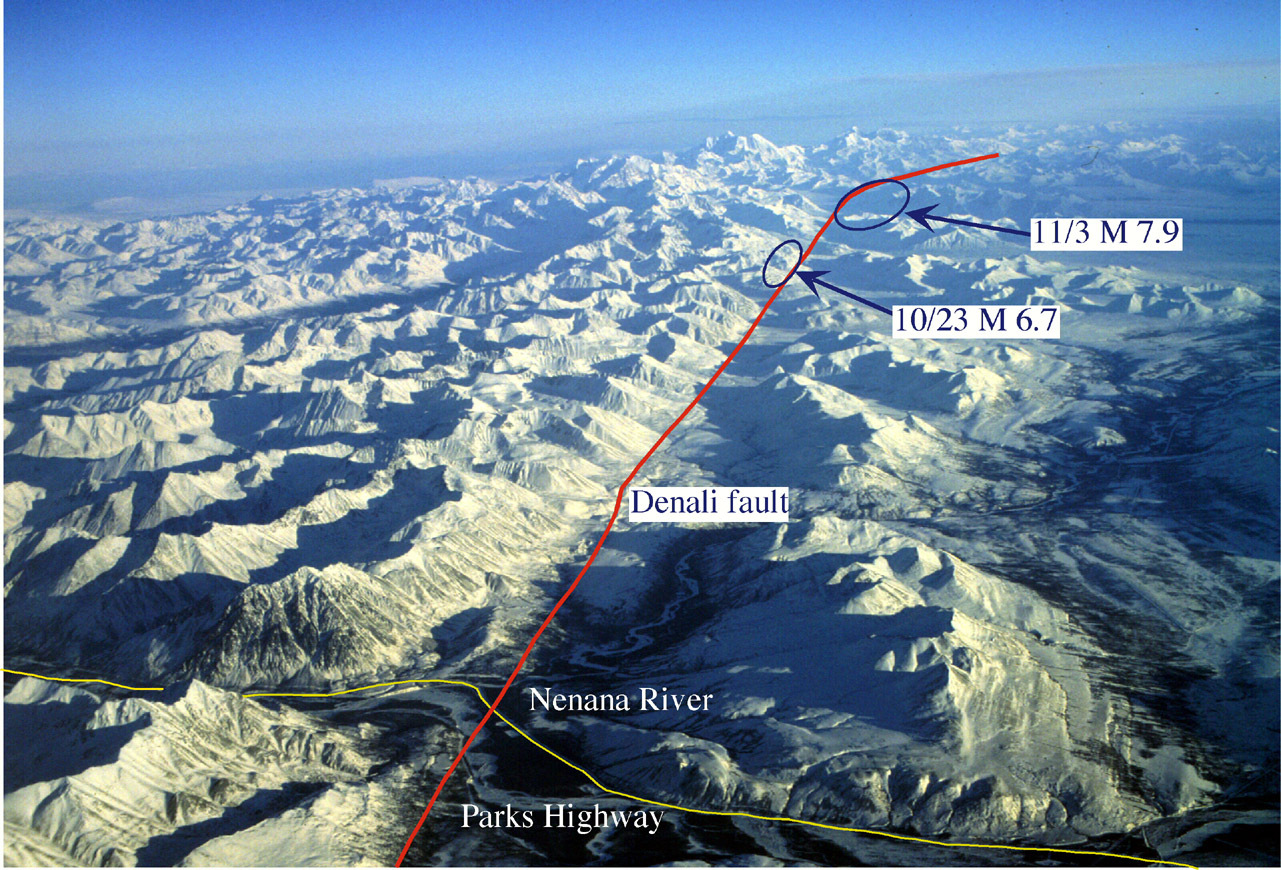

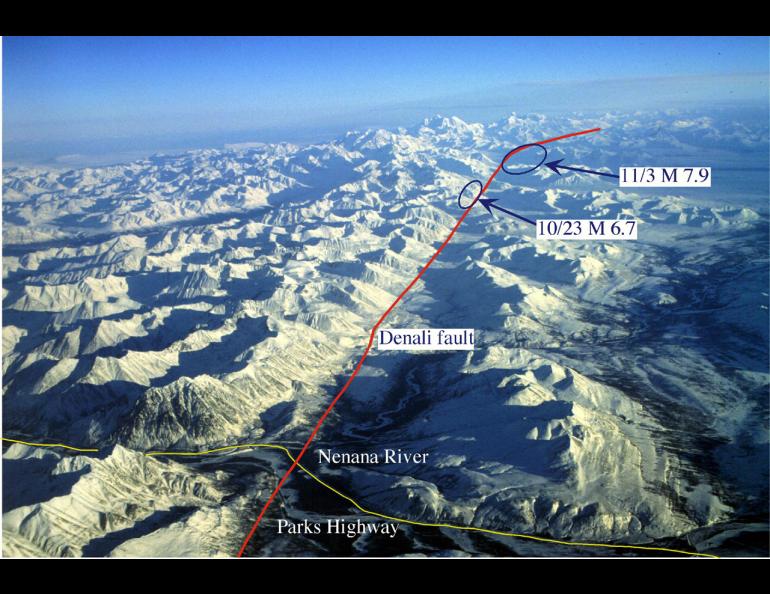

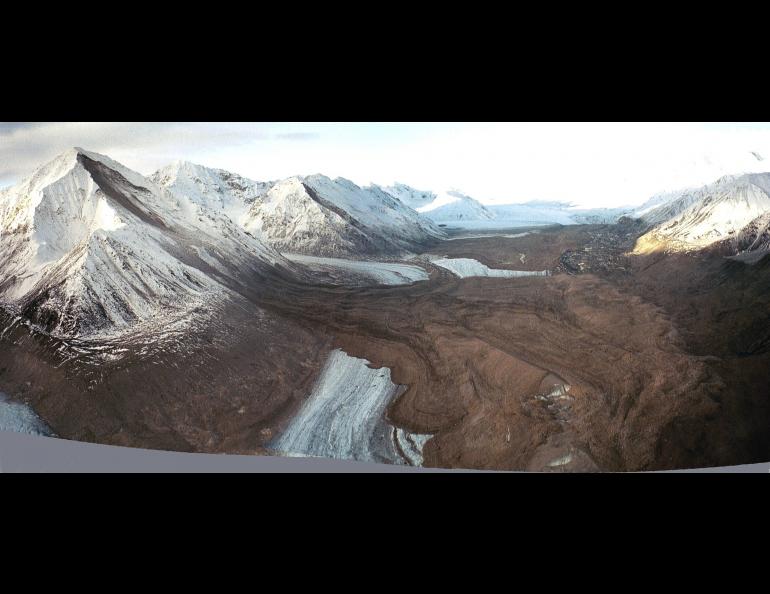

The Denali Fault cuts across Alaska in a line that on satellite photos looks like a canal dug through the Alaska Range. The fault runs through the mountains west to east and then curves south along the path of the Alaska Highway. It crosses the Canada border through the town of Beaver Creek to Haines Junction, and on down to Haines. Glaciers fill much of the faults trench through the Alaska Range; the Canwell Glacier off the Richardson Highway is smack on the fault line, as is the upper Black Rapids Glacier, much of which is now coated with rocks from landslides. On the Parks Highway, the bridge over the Nenana River a few miles north of Cantwell stands in the fault trench.

Hansen said the earthquake unzipped the fault, tearing the ground in a line that stretches about 192 miles. Geologists from all over the world soon flocked to the area to measure and photograph offset highways, deep scars on the snowless ground, and the trans-Alaska pipeline, still intact but teetering on its supports in places.

The earthquake ripped through the Denali Fault in a southeast direction, with much of its energy moving in that direction, toward the small communities of Mentasta Lake and Slana. The earthquake damaged houses and water wells there, but no people died.

While those who live on the fault cleaned up or moved out, scientists scrambled to take advantage of an event they will experience once in their careers.

"I havent gotten any of my normal work done since it happened," Freymueller said. "For everybody around here, in addition to their full-time job, its another full-time job dealing with the earthquake. But its an opportunity we cant pass up."