Do melting glaciers make for bad oysters?

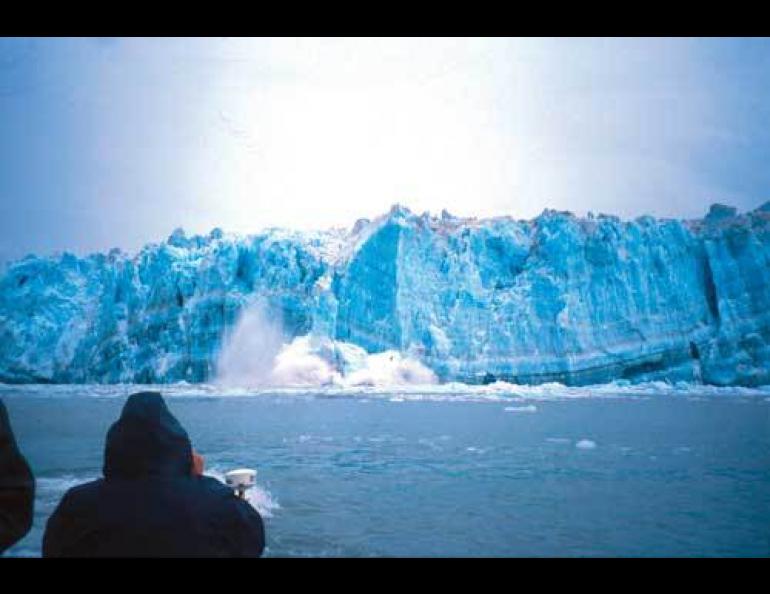

The rate of melting of Alaska's glaciers into the Gulf of Alaska has nearly doubled since 1995. In July 2004, passengers on a small cruise ship in Prince William Sound came down with stomach flu after eating local oysters. Some scientists think there's a connection between the two.

Tom Royer is an oceanographer with Old Dominion University in Virginia. Before he moved there, he was at the University of Alaska from 1969 to 1998. One of his duties for all those years has been to take readings of the temperature and the saltiness of the Gulf of Alaska. That long-term record shows that the ocean there has changed since measurements started in 1970.

“It's getting fresher, water temperatures are increasing, and it keeps warm water in the upper layers,” Royer said. “The bottom line is that everything's getting fresher and warmer.”

Those higher temperatures might have something to do with the oysters that caused people to get sick on the Prince William Sound cruise ship. A group of physicians found a type of bacteria that thrives only in water warmer than 59 degrees F (15 degrees C) in the oyster beds that supplied the cruise ship on Prince William Sound. The presence of the bacteria in Prince William Sound was a new northernmost record; the closest people had found the bacteria before 2004 was in the Pacific about 600 miles south.

“Rising temperatures of ocean water seem to have contributed to one of the largest known outbreaks of V. parahaemolyticus in the United States,” ten researchers wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2005.

Royer thinks the physicians are right on with their hypothesis. Recent sea-surface temperatures near Seward, which is downstream of Prince William Sound as far as ocean currents are concerned, were the highest since measurements began in 1970. Water temperatures several times jumped above the 59 degrees favored by the harmful bacteria.

Including glacial melt, snowmelt, and rainfall runoff, the Gulf of Alaska is the largest freshwater discharge system in North America, Royer said, about 62 percent greater than the output of the Mississippi River. All that fresh water acts like a cap on top of the saltier ocean beneath. This causes more heating of the upper layer by the sun and less mixing with denser, saltier water below. In general, the more fresh water dumped into the northern ocean, the warmer the ocean becomes, Royer said.

He spoke of a positive feedback loop that goes something like this: Glaciers pump lots of fresh water into the Gulf of Alaska, and, due to differences in density between fresh and salty water, the glacial melt increases currents that travel northward and carry heat from the southern part of the North Pacific. That heat makes the north warmer, causing more precipitation and higher temperatures for Yakutat, Cordova, and other Gulf of Alaska towns. Those higher temperatures cause more glacial melt, which keeps the process going.

A warmer northern ocean could push some cold-loving fish out of the Gulf of Alaska and into the Bering Sea, Royer said. Changes in saltiness of the North Pacific might also alter the currents in the Bering Sea, Arctic Ocean, and possibly the global “salinity conveyor belt” that controls weather worldwide, Royer wrote in a paper that will appear in Geophysical Research Letters.