Evolutionary Frills Not Essential To Survival

The recent disclosure of fossil dinosaur finds on the North Slope adds another piece to a geologic and evolutionary jigsaw puzzle that will never be completed. Tantalizing puzzle fragments like these are what make the distant past so agonizingly close to scientists, although they know that they will never be able to solve the riddle entirely.

The fossil record provides ample evidence that at least 99 percent of all the species that have ever lived on earth are now extinct. For example, at the close of the Cretaceous period 65 million years ago, not only the dinosaurs, but a selection of primitive mammals, land plants, and fully one-fourth of the marine animal life that inhabited the shallow waters all vanished.

Yet the Cretaceous extinction was not the only one to have decimated life forms on the earth. Similar annihilations have struck numerous times since the first appearance of single-celled organisms in the ocean 3.5 billion years ago. The very punctuation of the geologic calendar is based on the disappearance of old orders of life and the emergence of new dominant life forms.

The idea of unimaginable catastrophes has long been popular as an explanation of the great global losses. In recent years, a team led by famed physicist Luis Alvarez and his geologist son, Walter, claimed that a worldwide layer of 65-million year old sediments, rich in the heavy element iridium, was the signature of a collision between the earth and an asteroid. The impact would have raised a vast dust cloud, blocking out the sun. They proposed that the resulting death of plants would have been fatal for many animal populations, and that this event marked the end of the Cretaceous.

The concept, like most new ideas, has its opponents. Its detractors claim that the switch from a reptilian to a mammalian world was not as sudden as is often imagined. Paleobotanist Leo Hickey of the Smithsonian points out that the plant extinctions stretched over a period of about 30 to 40 thousand years. Although this is almost instantaneous on the geologic time scale, it is difficult to relate to a phenomenon like a dust cloud which should last for a period of a few months to a few years at most. Such is the stuff on which scientific debate thrives.

Throughout the earth's history, there is one common thread that seems to bind together the survivors. The rule seems to be: keep it simple. If you've got a model that works, don't mess with it.

One of the most successful designs of all times was the trilobite (which looked something like a horseshoe crab). The trilobites' evolutionary history spanned over 300 million years. It appears that they devoted much of this time to tinkering with their basic design. There were many end products with truly bizarre and seemingly unnecessary appendages. Trilobites vanished in the great extinction at the end of the Permian, 225 million years ago. The cockroach was around to see it happen.

If you like sea shells similar to the chambered nautilus, you would have loved the ammonite. The basic ammonite during the Jurassic 160 million years ago was a straightforward, functional (and exceptionally large) sea snail. The design was a success. As time went on, though, the ammonite added spikes, spires, adornments, and an astonishingly convoluted and complex arrangement of partitions between its interior chambers. It managed in the process to evolve itself out of existence. The dragonfly was alive to see this and, sticking to its basic design, is still with us.

For over 140 million years the dinosaurs ruled the earth. We'll probably never know what really happened to them, but it seems almost certain that all those frills that some of them began to develop toward the end were ornate beyond the need for simple defense. The cockroach and dragonfly could tell us, though, if they could talk. They were here when it happened.

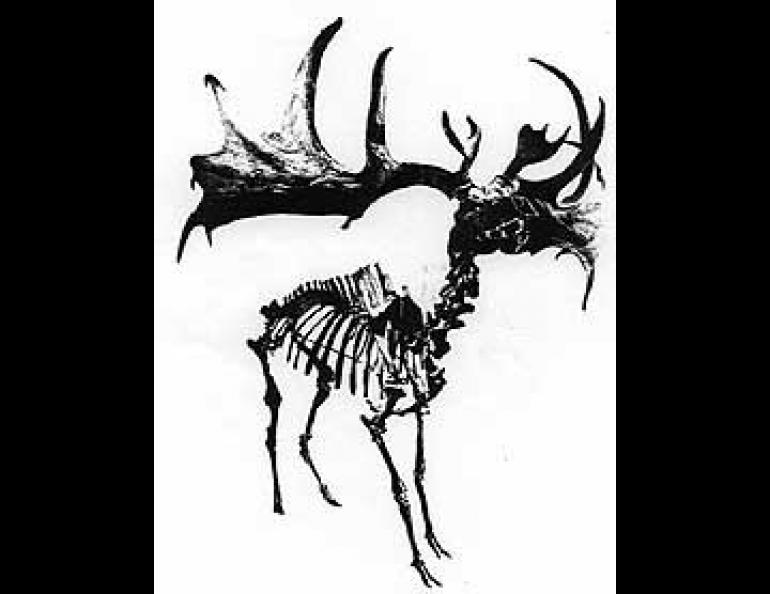

How about the really "modern" fossils--were they sometimes victims of experimental evolution? When the woolly mammoths' tusks crossed over one another, didn't they get in the animals' way? What about the saber-toothed tigers' awful overbite? The Irish elk had an antler spread of over 11 feet, the most of any member of the deer family. They became extinct less than 3000 years ago. Were those antlers really necessary?

Maybe 10 million years from now, some other creature will be looking at an ageless and unchanging cockroach or dragonfly -- wishing it could talk so that it could tell what happened to the most overspecialized species of them all, the human race.