The Exploding Guest Star of 1987

By order of the Caliph, Al Mamon, a magnificent astronomical observatory was erected at Baghdad in the year 829. It was immediately pressed into operation in a serious program dedicated to acquiring systematic and regular observations on the positions and brightness of the heavenly bodies. These important data indicated quite clearly that the stars were fixed rigidly in position relative to one another, as expected and totally in accord with the ideas developed by ancient Sumerians and Greeks, who believed that the stars of the sky are indelibly inscribed on a stellar "firmament".

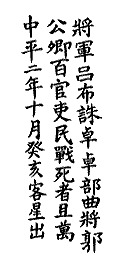

Imagine the horror, then, when medieval astronomers awakened one day in 1006 to find a new "guest star" in the heavens. It flared up suddenly, creating a commotion in Baghdad and being well recorded in Chinese and Japanese historical records. According to the Sung-Shih biographer, it was a baleful yellow star, no doubt portending warfare and ill fortune.

New stars, "guest stars", supernovae -- all the same thing -- are rare, only a few bright ones occurring in a thousand years. Nearly everything we know about ancient supernovae stems from Chinese historical records, which began to record all events in the sky about the time of the Chou Dynasty (circa 1100 BC). These records become extraordinarily complete from the beginning of the Han Dynasty (100 BC) and the Chinese chronicles tell of guest stars appearing in AD 185, 1006, 1054 (Crab Nebula), 1181, 1543, 1572 (Tycho's star) and 1604 (Kepler's star). The latter stars were noted not only in numerous Chinese records, but also in Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese literary works.

Unfortunately, no nearby supernovae have flared up since telescopic astronomy began 378 years ago, when Galileo trained his primitive instrument on the heavens. Astronomers have been waiting with impatience for one ever since.

The big event finally occurred on 23 February 1987. The new supernova was detected by Ian Shelton at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile when he developed a photographic plate taken during a routine patrol of the Magellanic clouds to search for variable stars; he found an image of a bright star that had not been there the night before! The star was bright enough to see with the unaided eye. Within a matter of days, telescopes on earth and on satellites spinning overhead were deployed on the new star, observing its every wiggle in great detail. The amount of scientific information from this full array of modern equipment has increased our understanding of exploding stars many fold in just the past two months.

The supernova of 1987 reached approximately the brightness of the dimmest star in the Big Dipper constellation; it certainly can't rival the great stellar event of 1006, which was as bright as Venus and could be seen at mid-day. The new "star" is deep in the circumpolar southern sky and therefore visible to only a small fraction of humanity. To see it really well, you have to go to Australia, South Africa or southern South America. In April, I tried to see the supernova from the Island of Hawaii, but found it difficult as it was low in the southern sky.

Observations indicate that the debris from the titanic explosion is expanding outward into space at 40 million miles an hour (6% of the speed of light).

The explosive energy released by this star is so gargantuan that it can't really be comprehended. It is, for example, about a hundred million million million times larger than the cataclysmic asteroid impact that is thought to have destroyed a large fraction of life on earth (including all dinosaurs) 60 million years ago. It is greater than a million million million million full blown exchanges employing all the world's nuclear weapons stockpile.

Fortunately, this titanic event occurred in a galaxy far, far away -- at least as we think of "far". The supernova is in the large cloud of Magellan, which astronomers think of as in our immediate neighborhood. The distance to it is so vast, however, that it has taken hundreds of thousands of years for the signal to reach the earth.