The first satellite's Alaska connection

On any clear, dark night you can see them, gliding through the sky and reflecting sunlight from the other side of the world. Manmade satellites now orbit our planet by the thousands, and it’s hard to stargaze without seeing one.

The inky black upper atmosphere was less busy 50 years ago, when a few young scientists stepped out of a trailer near Fairbanks to look up into the cold October sky. Gazing upward, they saw the moving dot that started it all, the Russian-launched Sputnik 1.

Those Alaskans, working for the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, were the first North American scientists to see the satellite, which was the size and shape of a basketball, and, at 180 pounds, weighed about as much as a point guard.

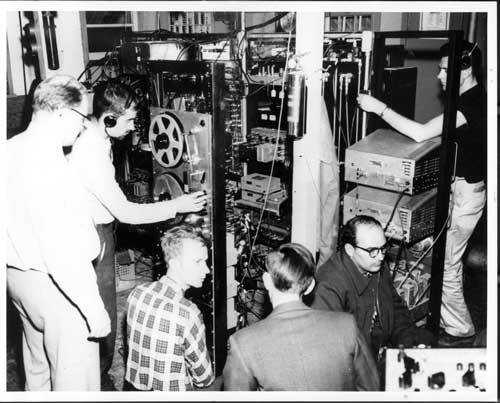

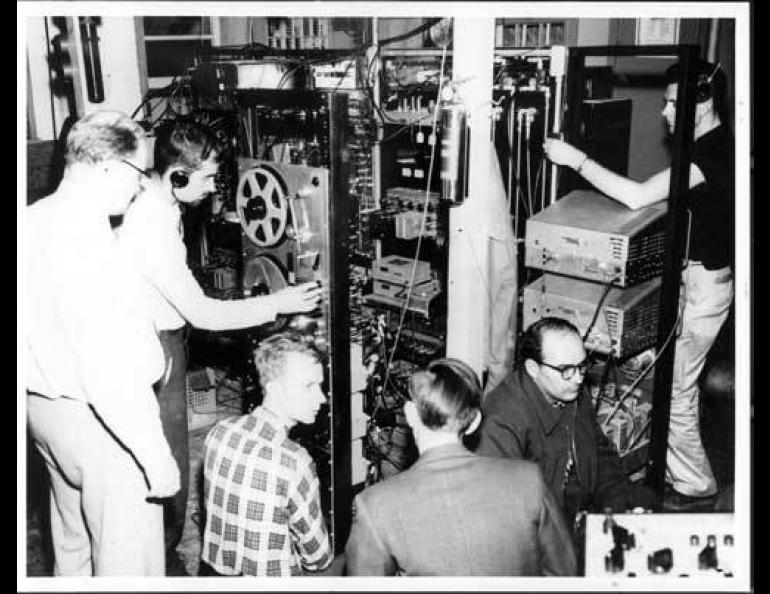

The Alaska researchers studied radio astronomy at the campus in Fairbanks. They had their own tracking station in a clearing in the forest near Ballaine Lake on the northern portion of university land. This station, set up to study the aurora and other features of the upper atmosphere, enabled the scientists to be ready when a reporter called the institute with news of the Russians’ secret launch of the world’s first manmade satellite. Within a half hour of that call, an official with the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington D.C. called Geophysical Institute Deputy Director C. Gordon Little with radio frequencies that Sputnik emitted. It was time to scramble.

“The scientists at the Institute poured out of their offices like stirred-up bees,” wrote a reporter for the “Farthest North Collegian,” the UAF campus newspaper.

Crowded into a trailer full of equipment about a mile north of their offices, the scientists received the radio beep-beep-beep from Sputnik and were able to calculate its orbit (click to listen to a recording of the radio signal from Sputnik). They figured it would be visible in the northwestern sky at about 5 a.m. the next day. On that morning, three of them—Joe Pope, Bob Leonard, and Gian Carlo Rumi—stepped outside the trailer to see what Little described as “a bright star-like object moving in a slow, graceful curve across the sky like a very slow shooting star.”

For the record, scientists may not have been the first Alaskans to see Sputnik. In a 1977 article, the founder of this column T. Neil Davis described how his neighbor, Dexter Stegemeyer, said he had seen “a strange moving star come up out of the west” as he was sitting in his outhouse. Though Stegemeyer didn’t know what he saw until he spoke with Davis, his sighting was a bit earlier than the scientists’.

The New York Times’ Oct. 7, 1957 edition included a front-page headline of “SATELLITE SEEN IN ALASKA,” and Sputnik caused a big fuss all over the country. People wondered about the implications of the Soviet object looping over America every 98 minutes and whether it meant the Russians also had the smarts to produce ballistic missiles that could carry nuclear warheads from Europe to the United States. Within a year, Congress voted to create NASA.

Fears about Sputnik evaporated as three months later the U.S. launched its own satellite, Explorer 1, and eventually took the lead in the race for space. Fifty years later, satellites are a part of everyday life. The Global Positioning System network allows precise navigation by airplane pilots, hikers, and others, and gives scientists the ability to track to movement of Earth’s plates, which grind along at about the speed that our fingernails grow. Satellites also have given us the first look at sea ice from above, and this fall they show an open Northwest Passage.

The next time you see a satellite streaking through the night sky, remember the first scientist on this continent to see one was standing right here in Alaska. And the first non-scientist to see a satellite in North America was sitting right here in Alaska.