Glacier, bay, glacier, bay, glacier, Glacier Bay

During the last 11,000 years, Glacier Bay has been filled with ice and has lost its ice at least three times, according to scientists who sample the remnants of ancient forests first identified by naturalist John Muir in Glacier Bay National Park.

Daniel Lawson and David Finnegan have collected hundreds of samples from trees that grew within the bay between advances of the ice. Both men work at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab in Hanover, New Hampshire.

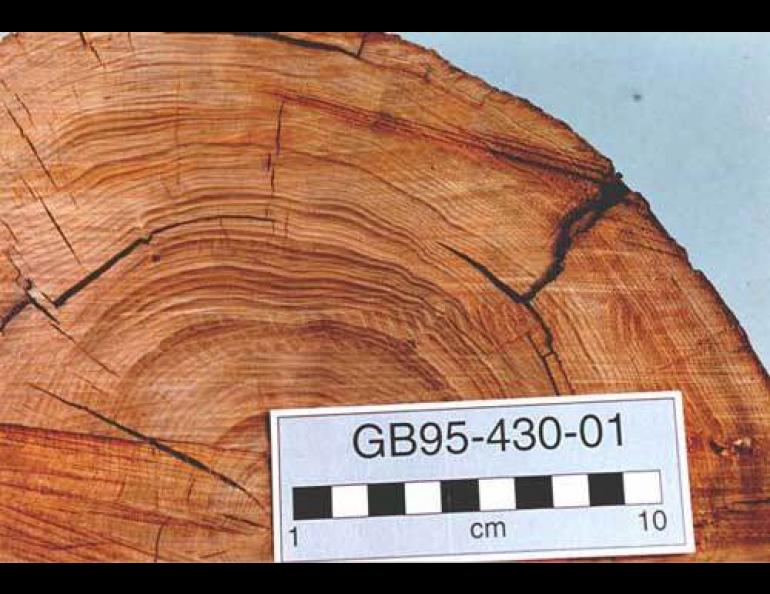

In 1989, Lawson started traveling to Glacier Bay in the summer, averaging about three trips each year. Finnegan joined the research group several years later. To get to their study sites, they drive a boat to the many inlets in the bay, go ashore, and hike up the newly exposed valleys in search of tree stumps. Some gray stumps are standing in positions they’ve held for thousands of years; advancing glaciers buried the bases of the trees with sediments, preserving them. Lawson and Finnegan core some trees and extract slices from others that show tree-ring patterns and then bring the wood back to their lab in New Hampshire. Lawson says the fieldwork is fun, and hard to beat when the weather is nice.

After documenting the location of the stumps with GPS receivers and collecting the samples, they radiocarbon date each sample to find out when the tree lived, which also tells them when an inlet was free of ice. Early results on Reid Inlet, where Reid Glacier has now backed up out of the ocean, show that the glacier had retreated beyond where it is now more than 10,000 years ago, advanced to the sea by 8,000 years ago, again retreated beyond where it is now about 7,000 years ago, and the ice once again advanced to Reid Inlet beginning about 5,000 years ago. Other glaciers in the bay have followed the same here-and-gone pattern over the last 1,000 or more years.

Why would Glacier Bay fill up and empty so many times in a relatively short amount of time? Lawson, Finnegan, and Richard Alley of Penn State University think fluctuations of the sun may be responsible. The sun has more punch during some times than others, and those periods of intensified solar activity might coincide with the beginning of ice retreats within Glacier Bay. Glaciers in the bay may have grown when the sun was weaker, such as it was during the Little Ice Age about A.D.1300. Lawson and Finnegan’s early results seem to support the sun/glacier connection, but they have much more work to do to confirm their idea.

Glacier Bay is one of the world’s great examples of fast ice loss—Captain George Vancouver reported a wall of ice at the entrance to the bay as he sailed by in the late 1700s, and a mass of ice one mile high and more than 50 miles long has disappeared since. Might advancing ice someday block cruise ships from one of Alaska’s most popular tourist attractions?

“If we get significantly reduced solar activity, then potentially, yeah. The bay could fill with ice again,” Lawson said. But solar fluctuations can take a long time from a human perspective; don’t plan on skiing the great Glacier Bay icefield anytime soon. Water skiing is the more likely option.

“Will the ice come back in our lifetimes? Probably not,” Finnegan said.