Goodbye to a giant of glacier research

High-school dropout Austin Post’s career began in the 1950s, when colleagues made up the title “Senior Meteorologist” to include him in a funding proposal.

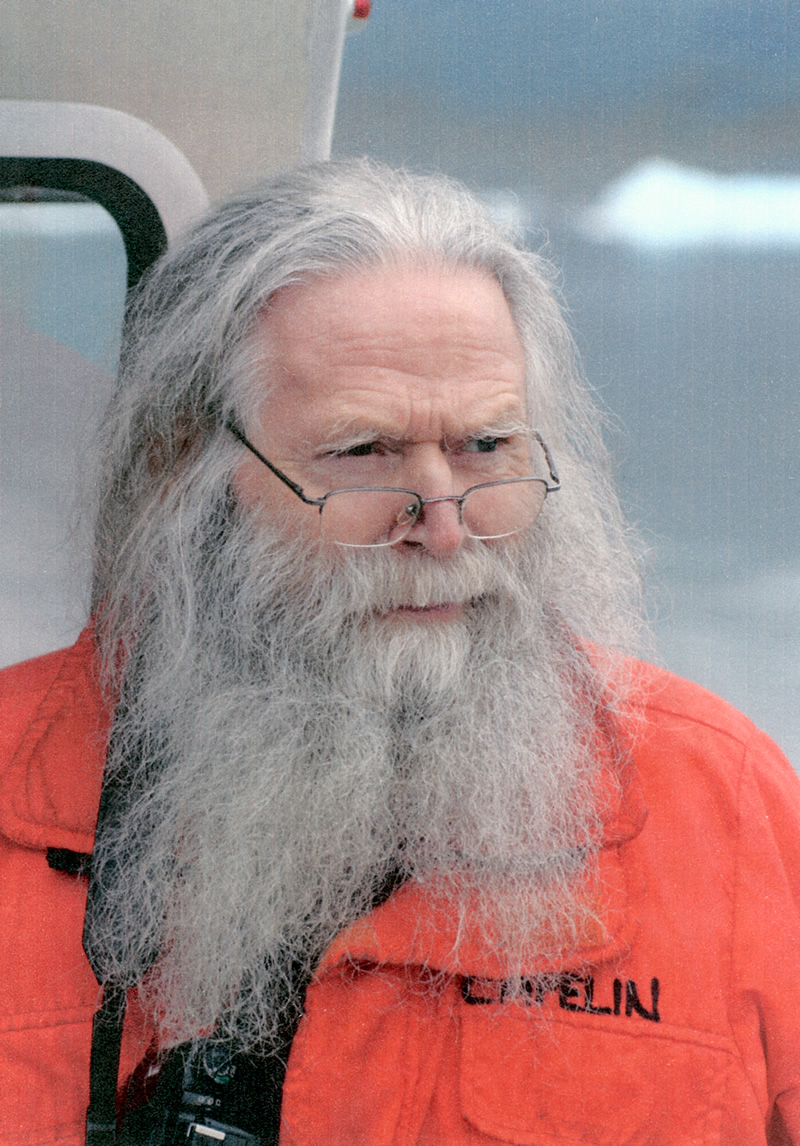

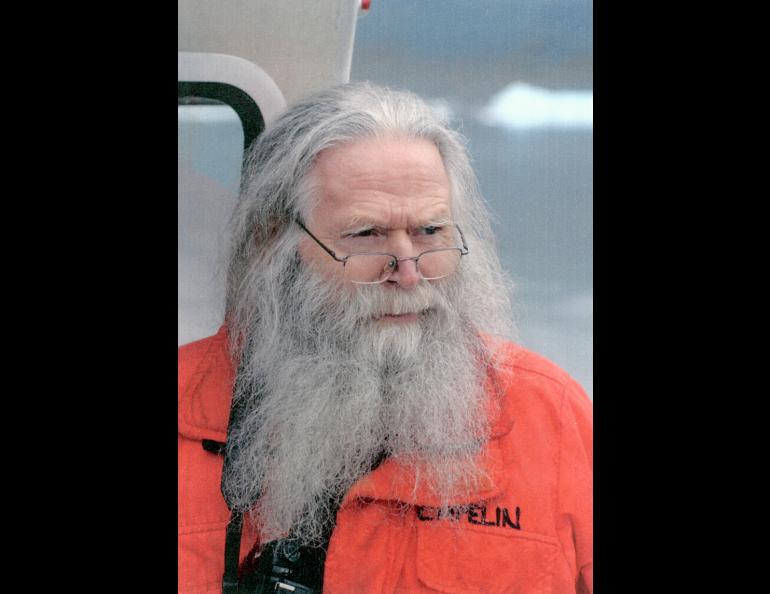

Post later recalled with humor that he misspelled both of those words on his application. Despite objections from the secretary that processed his paperwork, Post then embarked on a decades-long adventure of capturing images of North America’s glaciers from the open doors of small aircraft with 30-pound cameras. The pioneer in the field that so vividly shows climate change died at his home in Dupont, Washington, on Nov. 12, 2012. He was 90.

A mountain climber and carpenter in Washington, Post had a dream to photograph all the mountains of western America with glaciers flowing down their flanks. He made it to Alaska in late 1953, when his climbing buddy Larry Nielsen, a Monsanto chemist who was interested in the flow of glacier ice (which was similar to the deformation of plastics he worked with on his job) accepted a position on the Juneau Icefield Research Project. He invited Post northward to help him.

Post traveled to Alaska enthusiastic to map the Juneau Icefield, but contracted pneumonia on Lemon Creek Glacier. He would have died, he later wrote, if the University of Washington’s Dick Hubley hadn’t hiked to Juneau for penicillin and promptly returned to administer it to Post.

Hubley became a great friend of Post’s and an admirer of his photographs and his unusual power of observation. He hired Post for more Alaska glacier photography work during the International Geophysical Year of 1957.

In 1958, while leading a project on McCall Glacier in the Brooks Range, Hubley committed suicide. Out of respect for his friend, Post travelled north and continued Hubley’s work on the glacier.

As people discovered Post’s talents, they found ways to get him on their team. Mark Meier, then with the U.S. Geological Survey, remembers scrambling for a high school certificate “in lieu of subsequent accomplishment” for Post after the 1964 earthquake created an opportunity for fresh glacier photography. Some glaciologists thought that earthquake-released snow and rock that fell on glaciers caused them to surge (move downhill rapidly). Helped by the fact that Post had in 1963 photographed glaciers in areas that would be shaken by the earthquake, Meier secured a professional position with the U.S.G.S. to keep Post in the air. Post later debunked the theory that earthquake debris caused glaciers to surge.

Meier, director emeritus of the University of Colorado’s Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, said Post was born with a sharpened sense of observation.

“He was good at spotting the unusual,” Meier said. “He developed into a respected scientist, but initially he was just asking ‘why is this glacier advancing and others around it aren’t,’ and ‘why are some glacier moraines so beautifully contorted?’”

“He had incredible vision and imagination,” said retired glaciologist Larry Mayo of Fairbanks, who met Post in the 1950s. “He would be flying and say ‘That rock is 40 feet from where I saw it 30 years ago.’”

Post was fascinated at why some glaciers rushed downhill for a summer or two while others around them languished. Geophysical Institute professor emeritus Will Harrison first worked with Post at Variegated Glacier near Yakutat, which surged in the early 1980s.

“He was a pioneer who indentified interesting problems that defined fieldwork done in Alaska for the rest of the century,” Harrison said. “He defined surging glacier problems from aerial photographs and came up with the solution. He knew it was a plumbing problem even before our expensive work on it.”

Post also presented ideas on why glaciers that calve ice into ocean are prone to fast retreats even in times of climate cooling. Alaska's Columnia Glacier intrigued him, especially the changing depth reading where the glacier met the ocean. His curiosity led to the start of an enduring U.S.G.S program on the glacier.

For all his talents, Post didn’t get the accolades of some others with advanced degrees.

"Because he didn't publish much at first and he didn't go to meetings, he didn't get recognized beyond the Pacific Northwest or Alaska," Meier said, adding that Post "was bashful. He wouldn't stand up in front of a group and talk. One-on-one or with small groups he was fantastic."

"He had a mystique about him," University of Alaska Faibanks glaciologist Matt Nolan said. "HE had this acid tongue, was never sucking up to the man. He was definitely his own guy."

Nolan met Post about 10 year ago, when Nolan was working on McCall Glacier and saw Post's name on a climning report for a nearby mountain in 1958. Post once wrote that while he was "babysitting" Hubley's meteorological stations, he took "strenuous breaks" to bag nearby peaks.

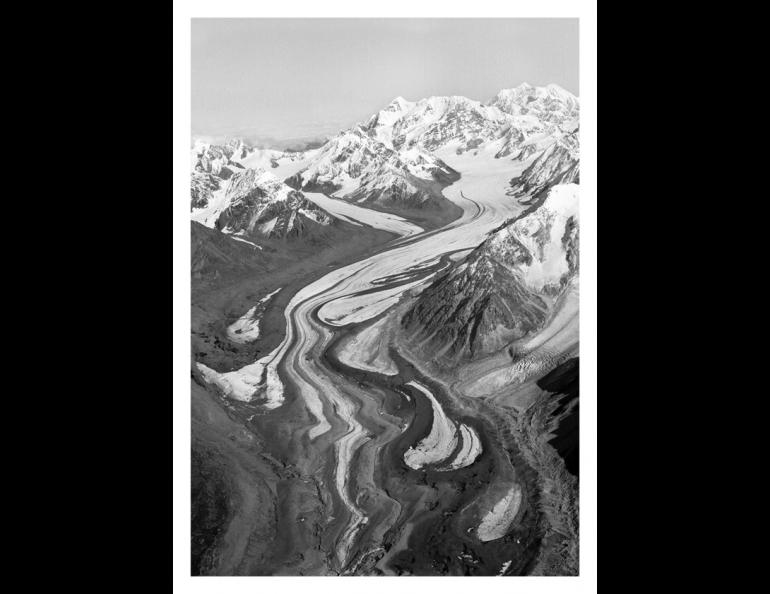

Knowing Post had been on McCall Glacier, Nolan found his phone number and called him. Three days later, Nolan received a shoebox in the mail full of medium-format photos of McCall Glacier. An oblique shot of the glacier excited him so that Nolan hunted down the spot and re-captured the image. His and Post’s photos, spaced 45 years apart, show an empty trough of gravel where uncountable tons of ice once sat. The side-by-side photos in 2004 appeared in newspapers around the world, which was satisfying for Post, then in his 80s.

“One of the best of his characteristics is he wanted to help others,” Meier said. “He loved to talk to students and show them his pictures.”

“Nearly everyone’s gotten a shoebox from him at some point,” Nolan said.

Nolan has now gone far beyond the shoebox. With a soft roar that sounds like a distant jet engine, a tabletop film scanner within Nolan’s home office in Fairbanks scrolls through nine-inch negatives uncoiling from 200-foot rolls of film. Nolan has received funding to gather Post’s films from an archive at the university, digitize them and share them online. The work is tedious but the reward is great, he said.

“The real value scientifically is that half of the photos are vertical, taken through the belly of the plane looking straight down. You can create topographic maps from those photos. That’s like launching a satellite today that gives you 40-year-old data.”

Glaciologists can compare Post’s photos — taken from the 1950s to the 1990s with a resolution equal to a 300-megapixel digital camera — to current images of a glacier to see how it has shrunk, retreated or perhaps advanced.

Post in 2004 received an honorary doctorate degree from UAF. Perhaps wanting to avoid a crowd, he did not come to Fairbanks to accept the award. Instead, UAF chancellor Marshall Lind traveled to Post’s Vashon home and handed him the diploma.

Post’s legacy lives on in the ideas about glacier behavior he deduced through his observations and photographs, a book of those photographs he authored with his friend and colleague Ed LaChapelle and in the thousands of negatives Matt Nolan is now scanning in his home.

“What’s really impressive about his archive is that it’s an archive,” Nolan said. “He took really good notes in flight. A lot of us take photos, but where are they in 10 years?”

Since the late 1970s, the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute has provided this column free in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer for the Geophysical Institute.