The Growth Of The Winter Snowpack In Alaska

Each winter, Alaskans are fond of discussing the snowfall and comparing how much fell in previous winters. It can be confusing, however, to relate the daily snowfall totals to how deep the snow is on the ground and to how much water will come out of the snowpack when it melts in the spring. The easiest way to understand this is to look at what goes on as the winter snowpack builds up.

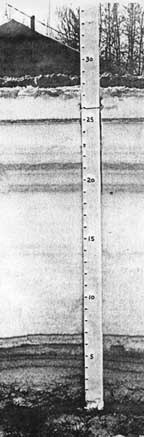

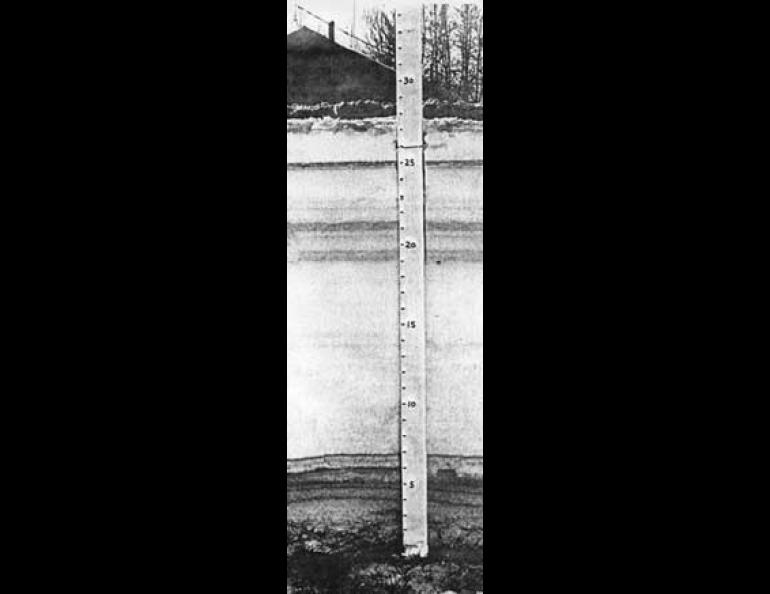

If you look closely at newly fallen snow, you will see the familiar six-sided pattern in most snowflakes. New snow tends to be fluffy and light if it is not windy. If you look at the same snow again a few days later, you will see that the snow particles have lost their original shape, and that they have become irregular crystals of ice. Also, the snow is not as fluffy as it first was. This is because it was compressed as it settled. As this process goes on, the snow layer becomes more compact, and the depth decreases even though there has been no melting. The daily snowfall totals for the winter in Fairbanks, up to March 35 when the accompanying picture was taken, added to 93 inches. The snow settled throughout the winter to a depth of just under 28 inches--or down to only 30% of the total snowfall. This settling and compacting is typical for Interior Alaska. On the northwest and Arctic coasts of Alaska, the picture is much different. Persistent wind packs the snow down much more tightly, and big snow drifts build up. On the other hand, in the southern coastal areas of Alaska, wind storms and periodic rains compact the snow further, sometimes creating ice layers within the snowpack.

Measuring the water content of snow--that is, determining how much liquid water is obtained by melting the snow layer--is a more meaningful way to record the amount of snowfall than by measuring the depth. Although the total depth of the Fairbanks snowpack is almost 28 inches, its water content when melted is close to 6 inches or roughly 20% of the depth of snow--characteristic for spring snow in the Interior.

An enlargement of the photograph of the Fairbanks snowpack revealed 33 separate layers of snow, each of which could be traced to snow storms or dry spells. Each snow storm during the winter adds a layer to the snowpack. In the spring, before melting begins, the snowpack reaches its maximum water content. In parts of Alaska with little wind, such as the Interior, very little of the water is lost by evaporation during the winter--probably less than a quarter of an inch. In windy areas like the Arctic coast, wind-blown snow can lose a considerable amount of water by evaporation as it is moved about. In the Interior, however, most evaporation takes place near the ground, but this is refrozen near the top of the snow, causing the familiar crust on top and the fragile hoer frost near the ground.

The heavy snowfall in Fairbanks during December 1984 is the thick white layer from 7 inches to 19 inches above the ground. The 47.7 inches of snow that fell from December 15 to 26 settled into a layer 12 inches thick. The gray band about 14 inches above the ground represents a break in the snowfall and lower temperatures from December 19 to 20. The six layers in the first 7 inches of this cross section were built up during light snowfalls from mid-October to December 8. The dark black band about 25 inches above the ground was formed during the dry, cold weather from February 16 to 24. This was the coldest time of the winter in Fairbanks; temperatures dropped to 40 below or lower on six days. The dust from auto emissions and fuel oil burning is heavier at cold temperatures, and this explains why this layer is especially dark. Outside the city, there is usually not enough dust to leave markings like this in the snow.

Image Caption cont: The light layers develop during days with heavier snowfall. This is similar to tree rings: when the snowpack is growing rapidly, a light layer is formed, and when the snowpack is growing slowly or not at all, a dark band is formed.