Icy Bay glaciers get up and go

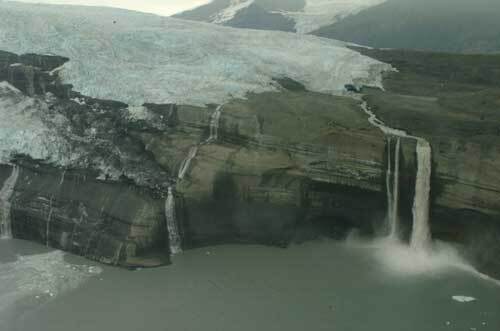

Until this spring, pilot Paul Claus would land a Supercub on a gravel bar in Icy Bay to give people an up-close look at a calving glacier. This year he can’t land there because a glacier has rumbled over the gravel bar. The main glaciers in Icy Bay crept forward up to one-third of a mile sometime between August 2006 and August 2007.

“At least three glaciers in the same bay have advanced in one year,” said Chris Larsen, a scientist at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, studying the ever-changing landscape of the area. “To have them advance right now is kind of weird.”

Icy Bay, located just west of Malaspina Glacier on Alaska’s dynamic southern coast, is like a smaller version of Glacier Bay. Like Glacier Bay, Icy Bay didn’t exist when captain George Vancouver sailed past in the late 1700s. Vancouver’s ship artist painted a portrait of an ice wall where the mouth of the bay is currently.

With salt-water fingers, Icy Bay reaches about 25 miles deep into southern Alaska today. At the end of those fingers are the glaciers that recently advanced and may still be creeping forward—Guyot, Tsaa, and Yahtze. Larsen is puzzled by the glaciers’ advance because all three glaciers moved forward at the same time, possibly because of a high snowfall year in the upper reaches of the glaciers, or rainfall down low that could lubricate the glaciers’ sliding surface, the bedrock beneath them.

Larsen admits he is “grasping at straws” as to why the three glaciers are advancing, but he’s pretty sure it’s not because we entered a new ice age since last August. Tidewater glaciers—glaciers with tongues that dip into salt water—advance and retreat regardless of the warmth, or coolness of the air. Hubbard Glacier, for example, is threatening to bulldoze its way into Gilbert Point, north of Yakutat, as it keeps advancing. At the same time Hubbard and a few other tidewater glaciers are advancing, the vast majority of glaciers that begin and end on land are retreating.

Tidewater glaciers are indifferent to climate warming because of the effects of the ocean, and the shape of the surrounding landscape. These oceanfront glaciers often grow and shrink in a repeating cycle: Snows high in the mountains bulk up a tidewater glacier and force it to advance, the tip of its tongue shoving forward underwater mounds of gravel. The glacier eventually backs off the shoal into deeper water, which makes it calve more and retreat. When a glacier retreats to the head of a fiord and stops calving, another advance can begin.

The tidewater glaciers on Alaska’s southern coast have advanced and retreated for a long time, but weather patterns in the area since the mid-1970s have been warmer, according to Reggie Muskett, who is writing a chapter on Icy Bay as part of his Ph.D. thesis at the International Arctic Research Center at UAF.

Muskett referenced retired USGS glaciologist Wendell Tangborn, who found that temperatures at the nearest Alaska towns, Yakutat and Cordova, have been higher since 1979, and the mean winter temperature at sea level has been above freezing.

“That gives the potential for year-round melting at lower elevations,” Muskett said.

The area also has received much more precipitation in winter and late fall, most of it in rain, Muskett said.

“That gives the potential for having more water, which would promote more sliding,” Muskett said.

The scientists don’t know whether the advance of the Icy Bay glaciers is the beginning of a long-term push, or a blip before the next retreat. For now, they’ve advised their colleagues flying over the glaciers to take lots of photos this summer to see if the glaciers continue to push deeper into Icy Bay.