Identifying A New Population Of Aleutian Geese

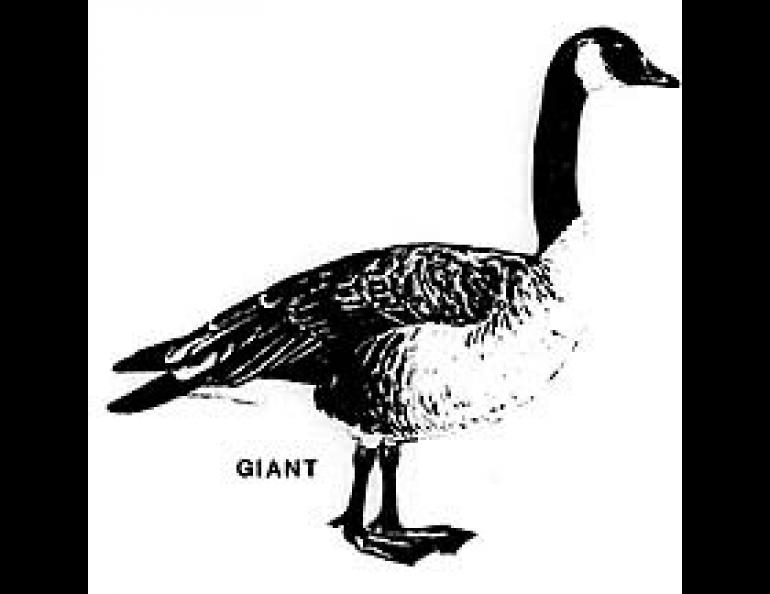

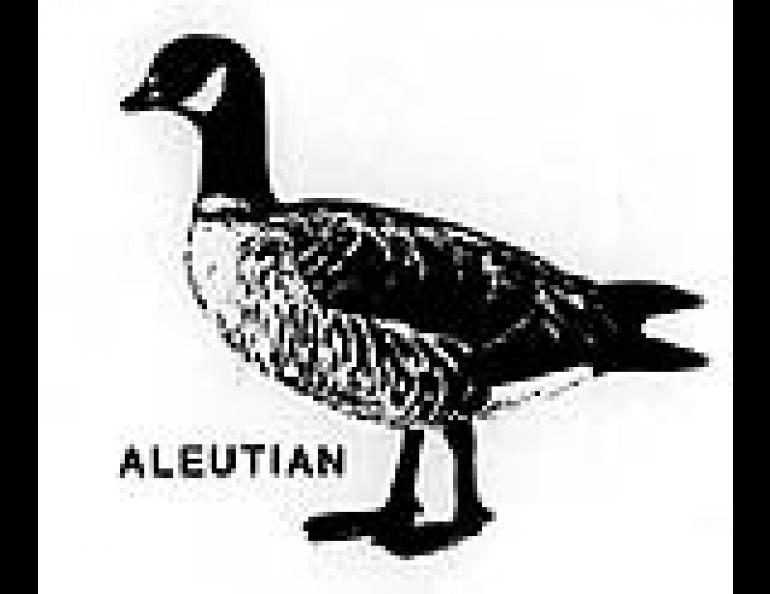

The Aleutian goose is a small and very rare variant of the Canada goose, heretofore believed to breed only on tiny Buldir Island in the extreme western Aleutians. Because of its rarity and presumed limited breeding range, it had been declared an endangered and therefore protected wildlife species.

It would hearten wildlife managers if there indeed was another population of these rare birds, but the problem facing them was to determine whether the geese that Hatch reported were actually Aleutian geese. If they were, the species' breeding range is actually more extensive than had been believed, so they are less threatened by immediate extinction. Then, however, pressure might be brought to withdraw the practice of protecting them.

The geese resembled the Aleutian strain in their size and plumage, but they also bore points of similarity to some mainland Alaska geese. Lacking the means by which to resolve the matter, Hatch and Dr. Calvin Lensink, leader of the Fish and Wildlife Migratory Bird Project, contacted Professor Gerald Shields, a geneticist and molecular biologist at the University of Alaska's Institute of Arctic Biology in Fairbanks.

Shields had already made plans to spend a research sabbatical year in the biochemistry laboratory of Professor Allan Wilson at the University of California in Berkeley. Wilson's lab is world renowned for its studies of the molecular relationships of organisms, and this presented Shields with a unique opportunity to help the wildlife managers resolve their problem with the newly found geese.

Over the next seven months, Shields used a number of "molecular tricks" to approach the problem. The avenue that showed the most promise was to analyze a type of the material of heredity itself, DNA, from the geese. This type of molecule, known as mitochondrial DNA, is relatively simple, occurs many times per cell, and most important, it mutates rapidly. Therefore, if different populations of geese had been isolated from each other for an appreciable length of time, the changes that had developed between them should be recognizable by differences in their DNA.

After analyzing over 5,000 samples, Shields concluded that Hatch had been correct in his original assumption, and that the geese from the Semedi Islands were, in fact, Aleutian geese. The DNA from mainland Alaska geese was clearly different, and that from geese taken from the lower 48 states was even more different.

Now that it has been established that the Aleutian geese actually have a more extensive breeding range than had been previously believed, policy decisions regarding their endangered status will probably be reevaluated. Nevertheless, none of the new findings change the fact that there are very few Aleutian geese. If they are lost, they can never be replaced. Scientists like Shields and wildlife managers alike hope that this never happens.