Melting Permafrost in Previously Forested Areas

The first things that come to mind when talking about damaged tundra are pictures of water-filled trenches created when bulldozers during WWII, or oil rigs during the ensuing years, marched across it without understanding or regard for its fragility. Once the thin protective insulating layer of vegetation is damaged or removed, the underlying permafrost begins to melt, creating, in time, mushy ditches that used to be roads. These will remain for centuries.

What is less appreciated is that equally damaging effects can occur in regions south of the vast, treeless expanses of tundra, when clearing and construction on ice-rich ground occurs.

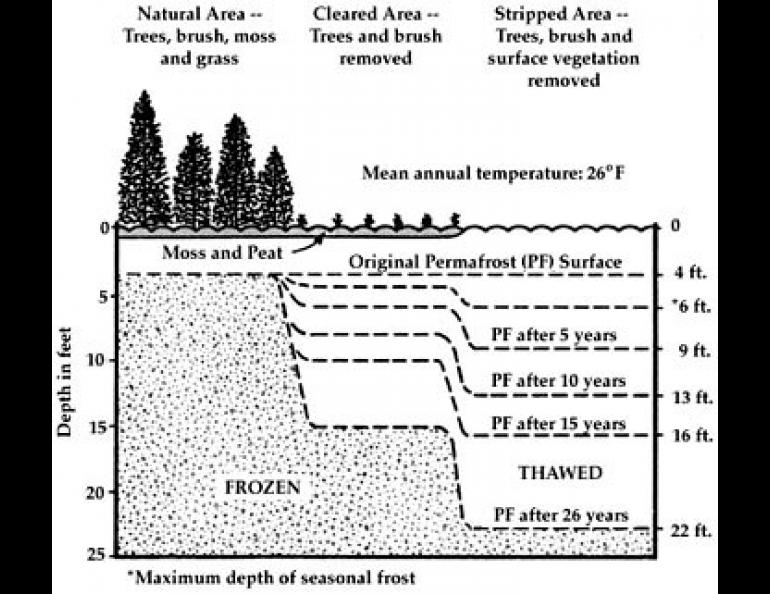

The Army Corps of Engineers took the problem seriously after the war when, in 1946, they established a long-term experimental station near Fairbanks to examine the relationship between vegetative cover and the stability of permafrost foundation material. Continuous monitoring under varying ground cover conditions were made for a period of 26 years. Kenneth Linell of the U.S. Army Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory has published a report on the findings.

First, the Army selected forested test plots about 3 miles northeast of Fairbanks near Farmers Loop Road. Here, the permafrost was estimated to extend to depths of at least 100 feet. The test areas were divided into three distinctive segments.

In the first, the natural vegetation was left intact. This amounted to a subarctic forest with white and black spruce, and a dense ground cover of moss, berries and other low plant growth.

In the second area, all trees and brush were removed to within about a foot above ground level and the major growth was kept trimmed, although a dense growth of shrubs, such as high-bush cranberries, was allowed to develop.

Finally, the third area was stripped bare to a depth of over a foot beneath the original ground level. Whenever new vegetation would begin to emerge, it was restripped. No attempt at snow removal was made on any of the test plots during the winter.

The permafrost levels measured at periodic intervals during the 26 years of the study revealed that any amount of removal of vegetation over ice-rich ground greatly increases the rate at which the underlying permafrost melts. Under the aboriginal forests, it remains stable, but clearing of any kind can have serious consequences on the foundation properties of dwellings, roads, airfields, and the like. Stripping invites total disaster.

To accelerate the problem, all one had to do was to build a heated structure over a cleared area, and it was practically guaranteed to sink out of sight within a few years. A splendid example is provided by the old KFAR broadcasting station on Farmers Loop Road near the University at Fairbanks. A visit to the site will reveal the curious sensation of encountering a colony of Lilliputians, since one must bend over to look into the windows from the outside.

The warming trend of recent Alaskan winters during the past few years may signal an even greater threat posed by thawing permafrost in the north. Paradoxically, the problem is not how to get rid of the permafrost--it's how to keep it frozen.