Microplastics low and high in Alaska

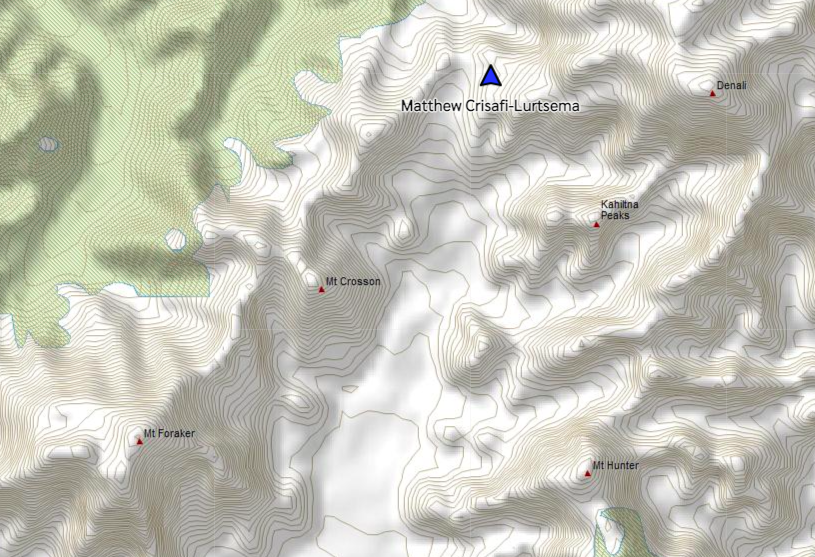

Two University of Alaska Fairbanks students are making their way up Denali while sampling for microplastics within the snow covering the 20,310-foot mountain. One of them, Matthew Crisafi-Lurtsema, has been sending back satellite texts, one each day since they flew from Talkeetna to Denali’s Kahiltna Glacier on May 8, 2024.

As of May 17, 2024, he and Roger Jaramillo are steadily progressing upward while scooping up snow samples along the way. When they return, they will analyze that melted snow for the presence of microplastics, which seem to be present everywhere else on Earth.

That includes lower elevations in Alaska, where a group of scientists from UAF’s Water and Environmental Research Center in 2020 and 2021 sampled snow and freshwater from more than 70 locations on a south-to-north transect, mostly along highways. Their recently published study showed plastic fragments everywhere they sampled, from the Kenai Peninsula to the North Slope.

“The results were concerning but not surprising, since people have found (microplastics) from the French Alps to Australia,” said Srijan Aggarwal, a professor of environmental engineering at UAF and a coauthor on the study. “It would be surprising if we didn’t have them here.”

Microplastics are fragments of the plastics we use many times each day. These particles — most that you need a microscope to see — are in the air we breathe as well as the water surrounding us.

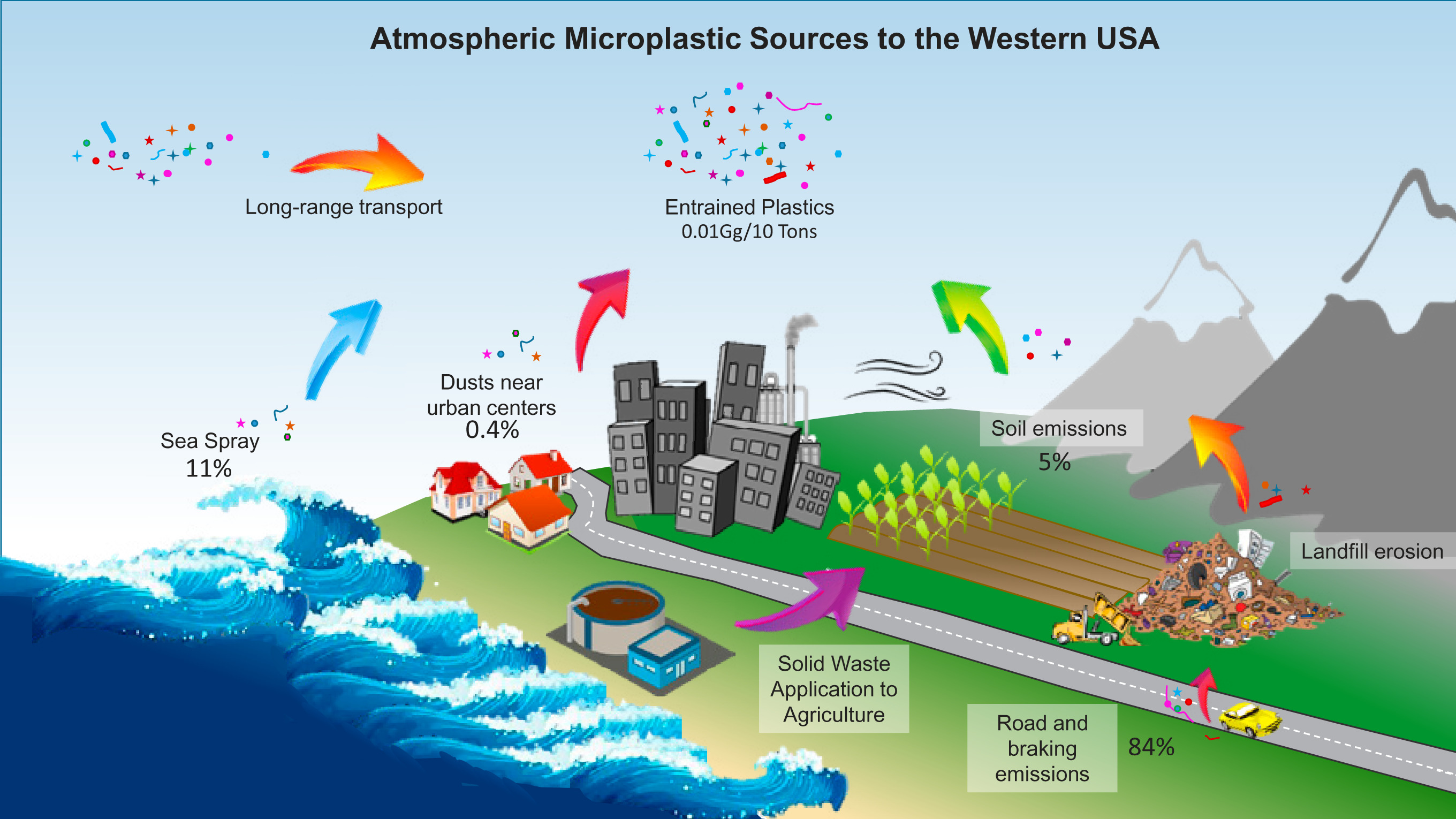

A major source of microplastics is the tires on our trucks and cars, which constantly shed synthetic particles that we can’t see. Brake pads also release plastic. Researchers recently determined that those two sources together account for more than 80 percent of microplastics now floating in the atmosphere of the western United States.

Aggarwal and his colleagues sampled water from Alaska sources such as the Lowe River near Valdez. They also sampled snow from the North Slope, including in Utqiaġvik, America’s farthest north community.

Subhabrata Dev, now an assistant professor of environmental engineering at the University of Alaska Anchorage, was a UAF postdoctoral researcher when he drove the highways of Alaska to collect water samples for the study. Others, including former UAF undergraduate student Davis Schwarz and researchers doing fieldwork in remote locations, gathered some of the 74 samples in the study.

They found the snowpack of Alaska north of the Brooks Range had high concentrations of tiny plastic particles. This was probably due to winds and large-scale weather patterns carrying plastics from far away. Researchers many years ago found pollutants from smelters and other Russian sources migrating to Alaska in what they called Arctic Haze.

Aggarwal and Dev don’t know the sources of the plastic particles they found during their sampling in Alaska. But Dev said pristine waterways that had lower plastic concentrations included the Lowe River, Blueberry Lake, Worthington Glacier, Castner Creek, the East Fork of Chulitna River, Bird Creek, Nenana River, Marion Creek, Carlo Creek, and Paxson Lake.

Snow samples that had some of the largest concentrations of microplastics came from the UAF campus, Utqiaġvik, and Turnagain Pass.

Those tiny plastics embedded in the snow might have traveled far to settle in Alaska. Scientists including Janice Brahney of Utah State University who are now researching “the global plastic cycle” noted that “under the right conditions, plastics can be transported across the major oceans and between continents.”