The missing polar bears of St. Matthew Island

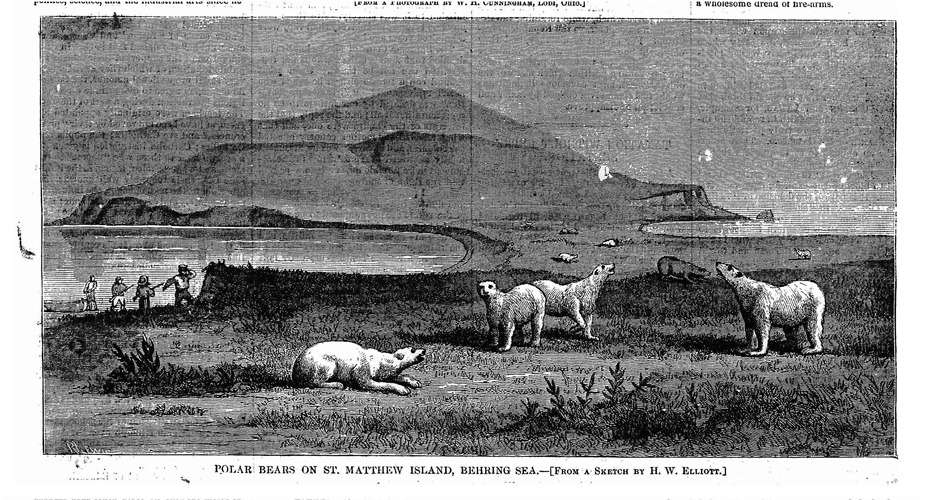

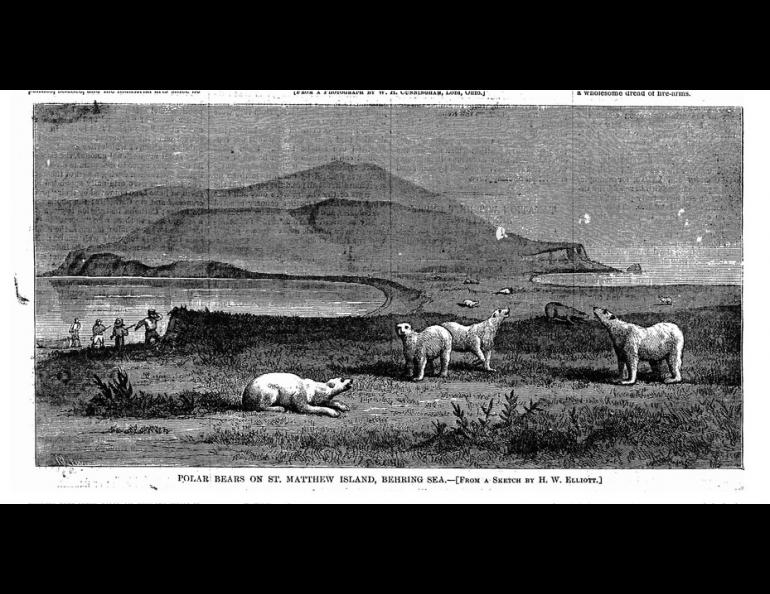

“We landed on St. Matthew Island early on a cold gray August morning, and judge our astonishment at finding hundreds of large polar bears . . . lazily sleeping in grassy hollows, or digging up grass and other roots, browsing like hogs.”

Henry Wood Elliott wrote this account for Harper’s Weekly Journal of Civilization in 1875. Elliott was a U.S. government biologist studying fur seals on the Pribilof Islands and overseeing the harvest of their skins, used to make fur coats. In 1874, he made a trip a few hundred miles north to St. Matthew Island to confirm the rumor of hundreds of polar bears that spent their summers on one of the most remote islands in the Bering Sea.

Elliott and his party explored the island for nine days and had polar bears in sight each minute. He estimated there were at least 250 bears on the island, and the bears seemed in excellent condition, though they were molting their winter fur. This summer, there are no polar bears on St. Matthew Island. None have spent their summers on the 32-mile long, 4-mile wide island in more than a century. In the summer of 1899, members of the Harriman Expedition visited St. Matthew and found — to their great disappointment — no polar bears.

What happened to the polar bears that summered on St. Matthew? A few scientists have pondered this question in a paper they will soon submit to a journal. The lead author is Dave Klein, who visited St. Matthew Island, part of the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, in the 1950s, 1960s, 1980s, and the 2000s.

Klein, a professor emeritus at the University of Alaska’s Institute of Arctic Biology is almost as active in research at 83 as he was when he was 63 and 43. In the paper he writes that people wiped out St. Matthew’s polar bears.

First came the Russians. Just before the United States purchased Alaska in 1867, a group of them overwintered on the island in hopes of harvesting a bounty of skins from polar bears and arctic foxes.

“The attempt was apparently a failure due to the severity of the winter weather and loss of lives of some of the Russians to scurvy,” Klein writes. Also, because seals are the main winter food source of polar bears, most of the bears probably were spending winters on the sea ice rather than on the island with the Russians.

Sailors on U.S. government Revenue Cutters put a dent in the St. Matthew summer polar bear population in the late 1890s. Patrolling the Bering Sea to prevent poaching of fur seals, seamen sometimes went ashore on St. Matthew and killed bears for the thrill of the hunt. Crewmembers of the cutter Corwin killed 16 polar bears on St. Matthew sometime in the 1890s. This is the last report of polar bears on the island, Klein writes.

In his decades of curiosity about the fate of the bears, Klein chatted with several people who suggested that Yankee whalers probably killed the last of St. Matthew’s polar bears. Recently, Klein had the chance to visit the New Bedford Whaling Museum and the New Bedford Public Library in Massachusetts. There, he read the logbooks from whaling ships that had been near St. Matthew in the late 1800s.

“Whalers, largely for financial reasons, were preoccupied with whaling at the edge of the receding ice,” Klein writes. “They could not take the risk of losing time for hunting and processing whales by putting crew members ashore for recreational hunting of polar bears.”

Klein thinks that the responsibility for the disappearance of polar bears from the island — which still features paths that polar bears pressed into the vegetation — probably goes to both the sailors on the Revenue Cutters and seal-hunting crewmembers from small Canadian and American schooners.

“Hunting crews were provided with ammunition in excess of their need for shooting fur seals, and when in proximity to land they were provided with opportunities to go ashore to hone their marksmanship on any wildlife they might see,” Klein writes.

He concludes that, in a different era, the U.S. government probably helped remove one of the most unique populations of animals in the country — polar bears living on a green island.

“It is ironic . . . that the Revenue Cutter Service, precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard, whose ships had been assigned to the Bering Sea to protect the northern fur seal from illegal exploitation also contributed in a major way . . . to the extirpation of the St. Matthew polar bear population. In fact, the 16 polar bears shot by the crew of a Revenue Cutter in the 1890s . . . may well have been the coup de grace.”