Nature's Twentieth-Century Technology

The sight of satellite dish antennas sprouting around the state drives home the point that, like it or not, Alaska has been yanked into the age of modern technology. But antennas of this shape are not really such a new concept at all.

The parabolic reflectors that form the dish antennas focus satellite signals on an element that is held in front of the dish. The same principle has been used for many years by astronomers who use reflecting telescopes with parabolic mirrors (a parabola is merely a geometric shape that reflects all incoming rays to a point). In the telescope, it is reflected light rays that are focused at a point. In the antenna, the rays are of radio wavelength. More mundane uses of parabolic reflectors can be witnessed on beaches, where sun-worshippers wear them around their necks to focus sunlight on their faces and speed up their tans.

But regardless of the uses to which people put the parabolic reflector, it can only be said that they are getting a late start. Nature has been using them for a long, long time.

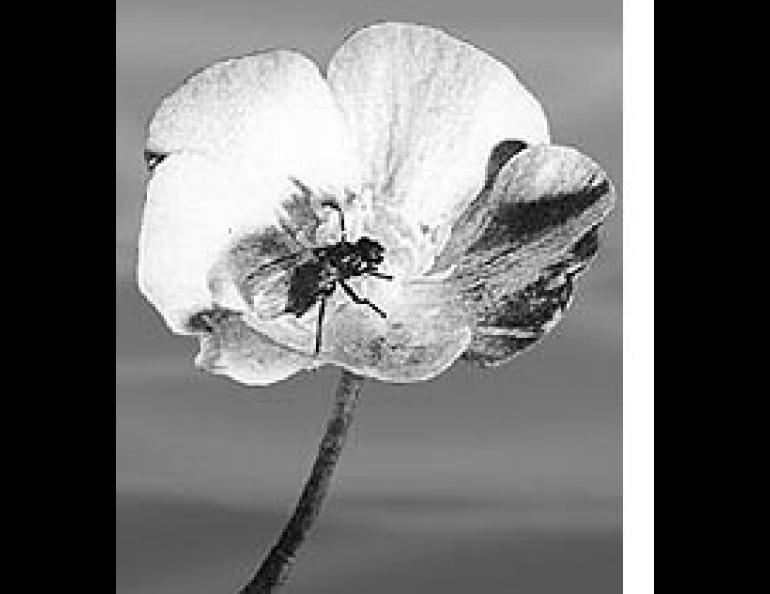

Fragile tundra plants need all the help they can get in utilizing the few months of almost perpetual sunshine in the Arctic. To do this in the most effective manner, flowers such as the Arctic poppy form near-perfect parabolic reflectors with their petals. These reflect the sun's rays out front onto the pollen-growing and seed-forming parts.

Better yet, the flower "tracks" the sun around the sky, in the same manner that a dish antenna tracks an orbiting satellite. This suncatching serves two purposes. First, the seeds and pollen are kept at a temperature a few degrees warmer than the surrounding air, helping them to develop more rapidly. Second, this pocket of additional warmth attracts flies and other insects on cold days, and they unwittingly pollinate the blossoms.

You might notice that parabolic flowers like the poppy, which reflect sunlight out in front where it is needed most, are often of lighter colors which reflect well. Flowers of darker shades, which utilize the sun's warmth by absorbing rather than reflecting it, are usually of different shapes.

Tundra flowers also know about insulation. Many have hollow stems, which function as miniature greenhouses and may be 30 to 40 degrees warmer within than without. Some, such as the woolly lousewort, grow fur coats. Others, like Arctic cotton grass, create microclimates by growing into tussocks which insulate both the ground and the plant. Such a tussock may emerge from the melting snow from 4 to 10 days before its lower-lying neighbors, thus effectively providing itself with a longer growing season.

All in all, humankind has done all right for itself to figure out, in a few hundred thousand years, some of the tricks that it took many millions of years for the rest of nature to develop. But it can still be a humbling lesson to learn that we often don't do it nearly as well.