Northern Thunderstorms

Even during fair weather, small puffy clouds are common in northern skies. A warm area on the ground surface creates an updraft carrying moisture up which condenses to form clouds. Each cloud might last only a few minutes, especially if the nearby air is dry.

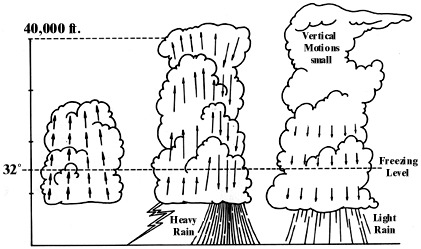

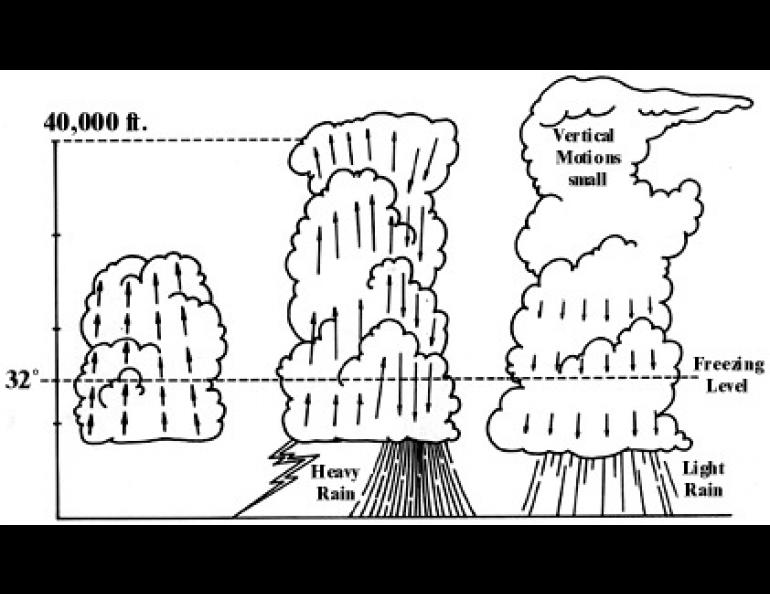

But when the moisture content of the middle atmosphere is high, and if the temperature decreases rapidly with altitude, minor updrafts can develop into major upward convective flows. Tall thunderclouds appear, reaching to altitudes above 20,000 feet (6,000 meters) as air rushes upward carrying moisture high above the freezing level.

In the upper part of the cloud the moisture particles condense into water droplets and ice particles. For a time these may be carried upward on the rising air. As the droplets and particles grow in size they become so heavy that the pull of gravity becomes stronger than the force of the upward-rushing air. Then as the particles fall, they drag against the surrounding air and pull it down too. The descending air is also cooled by the cold ice and water particles and thereby becomes much heavier than the air outside the cloud, accelerating the downdraft. This, the mature stage in a thunderstorm's life cycle, is characterized by maximum rain, electrical effects, and wind gusts at the earth's surface.

As downdrafts begin to dominate the cloud--typically an hour or so after the cloud forms--the energy provided by the updraft is diminished. When the entire cloud consists of descending air, the thunderstorm exhausts itself and dissipates.

Huge thunderstorms, like the ones of middle and southwestern North America that can produce hailstones as large as baseballs, do not occur here in the north because of the lack of strong surface heating which helps to build the taller cells of overturning air within thunderclouds. Even so, thunderstorms are common enough in summer to be the cause of most fires in northern forests and tundra regions.