Nuclear Test Detection

What does it take to enforce a nuclear test ban treaty? First, before any other measures can be taken, the participating nations must be able to detect when other members of the treaty are cheating. During the past couple of years, there have been two instances of "sightings" that have remained unexplained, but which are thought by some to have been related to weapons tests. One of these was a flash sighted off South Africa by a satellite, and the other was an immense cloud seen from airliners over the sea off Japan. Neither of these sightings have been satisfactorily explained.

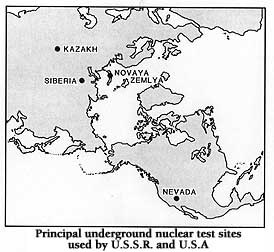

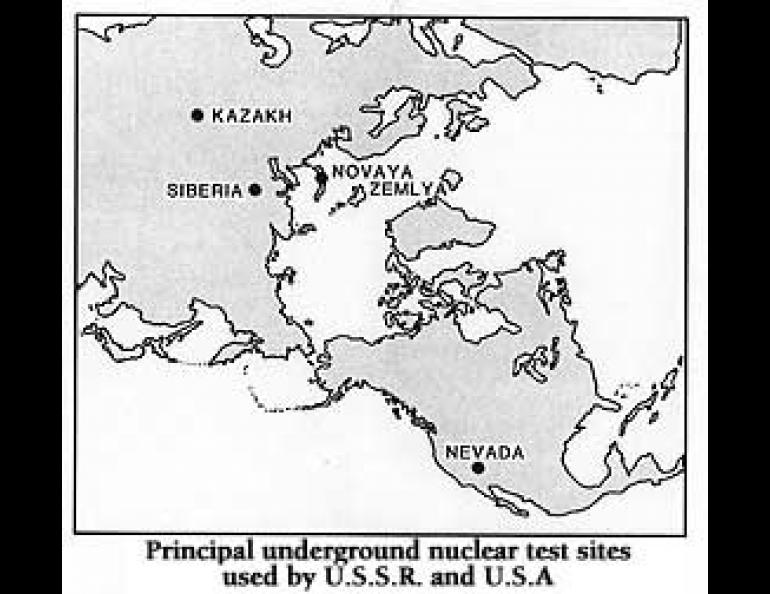

When nuclear tests are conducted underground, they are relatively easy to detect by seismographic means. Arms limitations talks with the Soviets appear likely in the near future, and it may be appropriate to take a look at what those detection capabilities are.

The limited test ban treaty of 1963 banned nuclear explosions in the atmosphere, under water, and in space. While this put an end to radioactive pollution of the atmosphere, both superpowers have carried on an extensive program of underground nuclear testing. In 1974, the United States and the Soviet Union signed a treaty agreeing to limit the yield of the warheads tested to 150 kilotons, and in 1977 the two countries (together with Great Britain) began formal talks on establishing a total ban on all testing.

The talks were suspended in 1980. In 1982, the U.S. declared it would not resume negotiations because of problems with verification, plus the fact that it was felt the Soviets might have violated the 150 kiloton limit.

But had they really? Seismologist Lynn Sykes of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory thinks not. Sykes and his colleague Ines Cifuentes have presented a paper published by the National Academy of Sciences in which they conclude that the seven largest Soviet explosions during the period 1976 through 1982 were all nearly identical in size at close to 150 kilotons. Proponents of Soviet cheating claimed actual yields ranging from 260 to 800 kilotons!

Why such a discrepancy? The amplitude (or "size") of seismic waves emanating from an underground explosion can be accurately measured. Because we can relate the amplitude of these waves to tests of known yield at the U.S. Nevada test site, it would seem that the same ratio of amplitude to yield should hold for the Soviet tests also.

Sykes and Cifuentes maintain that this just isn't so. They contend that the Nevada relationship does not hold for the Soviet Union because of differences in the earth's crust and upper mantle at the different localities. Because the crust of Nevada (and most of the western U.S.) is undergoing tectonic deformation, waves from tests at the Nevada test site are scattered from numerous faults and discontinuities. They therefore arrive at distant recording stations diminished in amplitude. Waves from tests in the Soviet Union, on the other hand, are conducted in tectonically stable areas, the rocks are relatively undisturbed, and seismic waves travel through them comparatively undiminished in amplitude.

Put another way, we have come to equate nuclear yield with seismic amplitude as it is measured from tests in Nevada. Because the crust is highly fractured in the western U.S., large explosions result in comparatively small waves eventually arriving at recording stations. But the crust in the U.S.S.R. is old, stable, and transmits seismic waves well. Therefore, waves from a fairly small test can be transmitted with a relatively large amplitude, leading observers to conclude that the yield itself was larger.

There is little doubt that, in today's world, it would be difficult to get away with cheating on a large scale. Sykes and Jack Evernden, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, believe that the state of technology is now such that it should be possible to detect clandestine tests as small as 0.1 kiloton, if instruments could be placed in the U.S.S.R. Skeptics take the view that, in order to disguise the yield of a test, all the Soviets would have to do would be to detonate it in a large underground cavity. This would effectively de-couple the explosion from the surrounding crust, and make the yield appear to be much smaller than it was. Sykes makes the point that, in order to conceal an explosion as small as 8 kilotons, it would be necessary to create a cavern as large as the largest Egyptian pyramid. Hardly worth the trouble, it would seem. And even then, surface evidence of such an excavation should be easily identifiable by satellite.