Oil Boreholes Hold the Permafrost Record of Alaska's North Slope

Max Brewer was 26 years old when he began measuring temperatures in abandoned oil-well boreholes on Alaska's north slope in 1950. Brewer was 77 when he returned last year to help scientists revive one of the longest-running permafrost-temperature experiments in Alaska.

Brewer, who now lives in Anchorage, spent 21 years in Barrow at the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory. Later, he was chief of operations for the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska for 17 years. While he held the latter position, Brewer arranged for the preservation of 21 oil-well boreholes in the petroleum reserve, which covers a good chunk of Alaska's north slope. Those boreholes, coupled with earlier ones and several around Prudhoe Bay, provide what some scientists consider the world's premier permafrost-temperature monitoring program.

Scientists today realize the value of permafrost measurements as a rock-steady indicator of past climate change, but scientists in the 1950s were more interested in the challenge of construction on frozen ground. Brewer and others used temperature data from oil boreholes to design roads, airstrips, hangars and garage foundations for the western third of the Distant Early Warning project, constructed across the Arctic from 1955 to 1957. The DEW Line was a chain of 63 radar and communications stations stretching 3,000 miles from the northwest coast of Alaska to the eastern coast of Greenland.

A side benefit of the early research was the recognition of permafrost as an indicator of climate change. In 1986, Arthur Lachenbruch used data from the northern boreholes to reveal in the journal Science that permafrost on the North Slope had been warming in the range of 2-to-4 degrees C during the last several decades. That much warming of such a stable medium made scientists realize permafrost, while not as dramatic as melting glaciers or calving ice sheets in Antarctica, had much to tell us about climate warming.

Permafrost-ground frozen for at least two years-lies beneath about 80 percent of Alaska's surface. On the North Slope, permafrost ranges in thickness from about 700 to as much as 2,240 feet thick, and may be as cold as minus 8 to minus 10 degrees C. South of the Yukon River, permafrost is much thinner and is often within one-to-two degrees below thawing temperatures. Some researchers have predicted severe damage to roads, pipelines, public buildings, homes and ecosystems when permafrost thaws.

Vladimir Romanovsky, a permafrost scientist at the University of Alaska's Geophysical Institute, became interested in Brewer's 1950s work after hearing of the boreholes from Jerry Brown of the International Permafrost Association. Romanovsky invited Brewer to Barrow at a Fairbanks meeting.

Brewer, who had lived in Barrow or had visited there almost every year since 1950, traveled there in 2001 with Huijun Jin, a University of Alaska graduate student who was helping Brewer evaluate some of earlier permafrost data. While up north, Brewer led Romanovsky and other researchers to some boreholes he had measured five decades earlier.

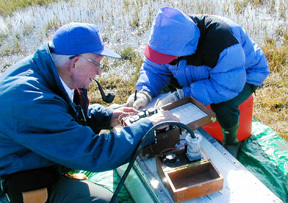

After thawing the accumulated ice in several of Brewer's boreholes using steam points and hoses, Romanovsky, UAF's Kenji Yoshikawa, Jin, Brown, and Austin Kovacs installed new temperature cables in the holes.

With the reestablishment of several of Brewer's boreholes and a look at some of Brewer's old data, Romanovsky got a chance to validate a computer model he had developed for predicting temperatures in North Slope permafrost. For the first time, he could compare his model results with real temperatures from 50 years ago. He liked what he saw.

"The actual temperatures were almost identical to the model predictions," Romanovsky said.

An accurate model will help Romanovsky predict future changes in Alaska permafrost, which underlies much of the state. He attributes much of what he learns to the pioneering efforts of people like Max Brewer, who numbed his fingers making measurements near Barrow half a century ago.