In Pursuit of Disaster

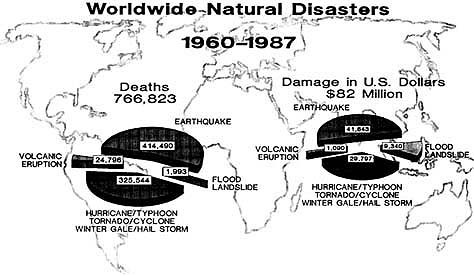

Humankind seems forever threatened by natural disaster. By the tens of thousands of people die in floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and storms. Yet as soon as the flood waters recede or the volcanoes slumber, residents return to the scene. Why don't they learn?

Actually, we often live in harm's way for very good reasons. What drives us to live in dangerous places lies in our species' determination to survive--and in geophysics.

People range over the sea in pursuit of fish, and the sea has been swallowing fishing boats since before the dawn of history. Water bodies offer the most economical form of transport, and most vessels arrive safely at port. But some don't, and storms bred at sea or over large lakes take their toll of shoreside settlements as well.

We farm for our food, and farmers naturally seek the best soils. Many of those have been deposited by flooding rivers as they spread over flat valleys. Sometimes the floods are too mighty, and the farmers' life work is swept away. Sometimes the farmers are too, along with neighboring settlements.

Wind operating over centuries has built up vast and fertile plains splendid for farming or ranching. Sometimes the wind has too much power, and tornadoes and gales take their toll.

Probably the most spectacular and hazardous form of soil enrichment is a volcanic eruption. When they're not coping with lava flows and ash falls, the grape growers on the slopes of Mt. Vesuvius do well. The rich soil of high tropical islands give us sugar cane and pineapples in abundance. It's only once in awhile that the fields vanish under poisonous gases or molten rock.

So the geophysical forces of a rotating, changing planet interacting with its sea and atmosphere complicate our quest for food: the best sources offer the most hazard. To a great extent, that's true for our needed minerals too. Processes that concentrate minerals into ores of value are intimately connected to the processes that build mountains, cause earthquakes, and propel eruptions. When we go for the gold, it's often through a high-risk obstacle course.

And the correct pronoun surely is we. Alaska sites make a showy catalog of hazard-prone habitations. Juneau, an unusual mine-mouth capital city, must zone for avalanche and engineer for earthquake. The 1964 earthquake associated by name with Anchorage was the mightiest North American quake since records have been kept on the continent. That upheaval in the earth's crust showed that Kodiak lay in tsunami country. Its residents already knew about the hazards of storms and seas.

The 1964 earthquake damaged Valdez with water, so severely the whole town moved--to its original site, from which it had been driven by winds. Residents of Unalaska and Dutch Harbor protest justly that their common hurricane-force gales are dismissed as winter storms. Volcanoes add considerably to the local scenery, as they do at windy and well-named Cold Bay.

North along the Bering Sea and into the arctic, volcanoes and earthquakes don't unnerve communities--but Nome, Kotzebue and Barrow endure Ice overrides as well as gales. Bethel has yet to find a way to keep from falling into the eroding Kuskokwim River, building by building.

Interior towns lie along rivers, and now and then vanish into them. The Corps of Engineers built a mighty flood-control project for Fairbanks that should hold the Chena. The Tanana is not so easily tamed, as the people of Nenena can testify. Too, the corps doesn't yet have an earthquake-control project on the drawing boards, and the Fairbanks area is perhaps overdue for its next magnitude 7 shaking.

Yet all these places have good reasons for existing--good enough for us, at least. It may be that in the matter of risking possible disaster in the face of probable gain, our philosopher of choice is Willy Sutton, the famous thief and escape artist of fifty-plus years back. When someone once asked him why he robbed banks, he answered, "Because that's where the money is!"