Recovery after world's largest tundra fire raises questions

Four summers ago, Syndonia Bret-Harte stood outside at Toolik Lake, watching a wall of smoke creep toward the research station on Alaska’s North Slope. Soon after, smoke oozed over the cluster of buildings.

“It was a dense, choking fog,” Bret-Harte said.

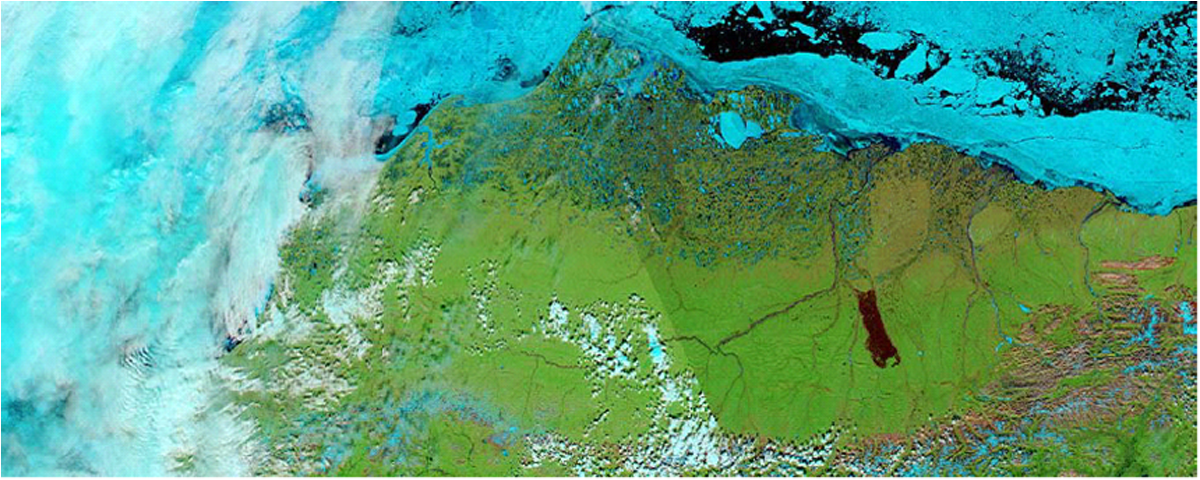

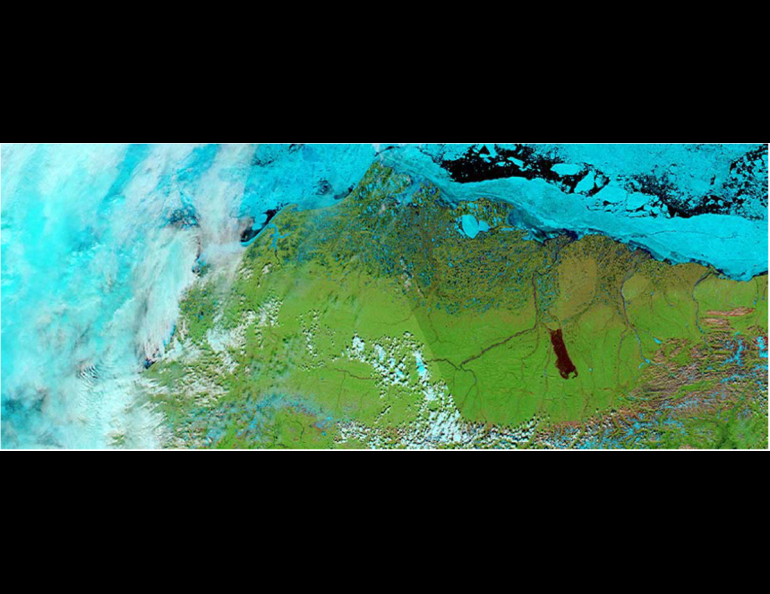

The smoke looked, smelled and tasted like what Bret-Harte has experienced at her home in Fairbanks, but the far-north version was composed of vaporized tundra plants instead of black spruce and birch. The 2007 Anaktuvuk River fire, which burned an area the size of Cape Cod, is the largest fire ever recorded in tundra. It was the first wildfire in the area since slaves were shoving blocks in place to create the pyramids in Egypt (about 5,000 years ago).

Bret-Harte and others working at the research station knew they were witnessing something unusual — or maybe seeing the future. They found funding to study the burn, and time in their schedules to get their feet on the black ground. The group of scientists, led by Michelle Mack of the University of Florida, collaborated on a study published recently in the journal Nature.

Bret-Harte, a plant specialist, just returned from a helicopter trip to the site of the big fire. Her close-up images show a green, lush landscape as the tundra recovers nicely after four summers.

“It’s not back to what it was before — the shrubs are small,” Bret-Harte said. “But in 10 years it will look pretty similar over much of the area.”

The new vegetation is photosynthesizing with such vigor that it is taking up as much carbon dioxide from the air as nearby tundra that did not burn in 2007, Bret-Harte said. This is quite a change compared to the staggering amount of carbon the fire added to the atmosphere four summers ago. The researchers calculated that the smoke from the 2007 fire spewed about half as much carbon dioxide as all arctic vegetation in the world sucked in during an average year.

If the tundra burned like that every year, in a flash the Arctic could turn from a place where carbon dioxide is pulled from the atmosphere and locked away, to a carbon dioxide generator that would further warm the world.

“The carbon that was lost in this fire represented about 30 to 50 years of accumulation in the soil,” Bret-Harte said. “But if you burned it again now, you’re getting into the deeper, older carbon. You’d be burning away this bank of carbon stored in the soil over thousands of years. That would be huge.”

Was the 2007 Anaktuvuk River fire a freakish, one-time event, or a sign of things to come? Bret-Harte said she doesn’t know, but she does know the conditions that led to the 2007 event. A lightning strike ignited the tundra in mid-July. Wet soils and vegetation snuff most tundra fires, but this one endured because of an exceptionally dry summer. The fire smoldered for a few months until dry Chinook winds curled over the Brooks Range in September, fanning the fire to life.

“It burned most of the area in five or six days,” Bret-Harte said.

Though the giant tundra fire of 2007 happened due to a combination of rare conditions, at least one of those factors is becoming more common. According to sensors maintained by workers for the Bureau of Land Management, lightning has struck Alaska’s North Slope much more frequently lately. From a steady hit rate of a few thousand lightning strikes from the mid-1980s until the late 1990s, lightning strikes have jumped to about 20,000 each year in the last decade. More lightning strikes and warmer summers might change what people know as a smoke-free northern Alaska.

Bret-Harte wonders, “Is this like a tipping point, moving us to a new regime on the North Slope?”