Reindeer tasting: Nice work, if you can get it

Using my tongue, I pressed the meat to the roof of my mouth. The folded slice oozed with a slight taste of blood. I chewed the sample, which was so tender it disintegrated. Then came the hardest part—I had to spit the meat into a cup without eating it.

Six of us, the “sensory panel” for the University of Alaska’s Reindeer Research Program, gathered together to sample reindeer meat from animals on the Seward Peninsula. We didn’t know we were sampling reindeer backstrap in two forms—one from a reindeer carcass that had been electrically stimulated, one from a carcass that had not.

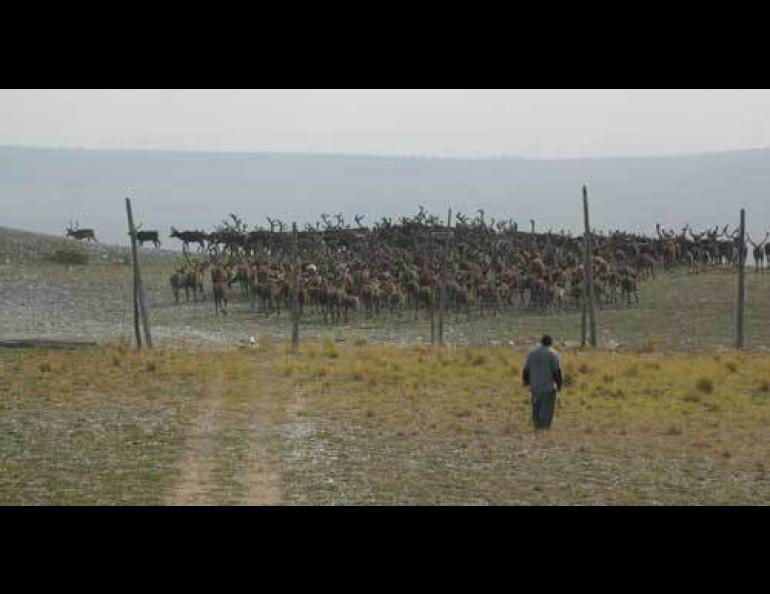

Eva Wiklund, a meat scientist and research associate professor with UAF’s Reindeer Research Program, had set up the experiment. Wiklund is from Sweden, where there are 2,500 reindeer herders and 250,000 reindeer grazing over almost half of the country. The scale of the reindeer industry is a bit smaller in Alaska, where herders on the Seward Peninsula are still trying to recover from the infiltration of the Western Arctic caribou herd in the 1990s. When caribou and reindeer mix, reindeer often follow caribou to places unknown. Once, 17 herders on the Seward Peninsula had reindeer. Now, seven have reindeer and their herds total about 7,000 animals. But things are looking up, according to Greg Finstad, manager of the Reindeer Research Program; caribou have withdrawn to the eastern part of the Seward Peninsula during the last three winters, and the herders sell meat to local people and village grocery stores.

“The industry has long-range plans to build and operate slaughter facilities under USDA inspection,” Finstad said. “There should be one up and running in two or three years.”

By that time, reindeer herders should be able to use results from Wiklund’s meat-tasting experiments. During her first tests, Wiklund gave us samples of reindeer backstrap from a herd of animals that roams the tundra just outside Nome. Some samples were from carcasses that workers stimulated with electricity; other carcasses didn’t undergo the treatment.

Sort of like attaching jumper cables and sending an electrical current through a carcass for a minute or less, electrical stimulation is a common practice beef producers use to speed up rigor mortis so large masses of meat lose heat quickly.

“You want to cool down a big carcass as soon as possible,” Wiklund said. “But if you blow cold air over carcasses without electrical stimulation, muscles may contract because of the cold, which will make the meat very tough. It doesn’t matter if you boil it for five hours—it will still be like a telephone book.”

Electrical stimulation also activates enzymes that break down protein structures in the meat, which often makes it more tender. In the first test, we tasters couldn’t tell the difference between electrically treated and untreated meat, possibly because backstrap is such a tender cut. But when Wiklund gave a larger group of consumers meat from the shoulder area of the same animals, a majority said the meat that had been electrically stimulated was more tender.

In a second experiment, Wiklund had us sample reindeer from Tom Gray’s White Mountain herd that he slaughtered in March, July, and November. We chose the November-slaughtered animals as having the most tender, juicy meat.

“When to slaughter animals is very important to what kind of meat quality you can expect,” Wiklund said.

Wiklund will also look at the protein, fat, vitamin, and fatty acid content of Seward Peninsula reindeer meat and will compare it to the results from the taste panel. Her goal is to help reindeer herders make the most of one of the best meat products available.

“I hope there will be some useful info when we’re done,” she said.