Sampling the air from Alaska to Arizona

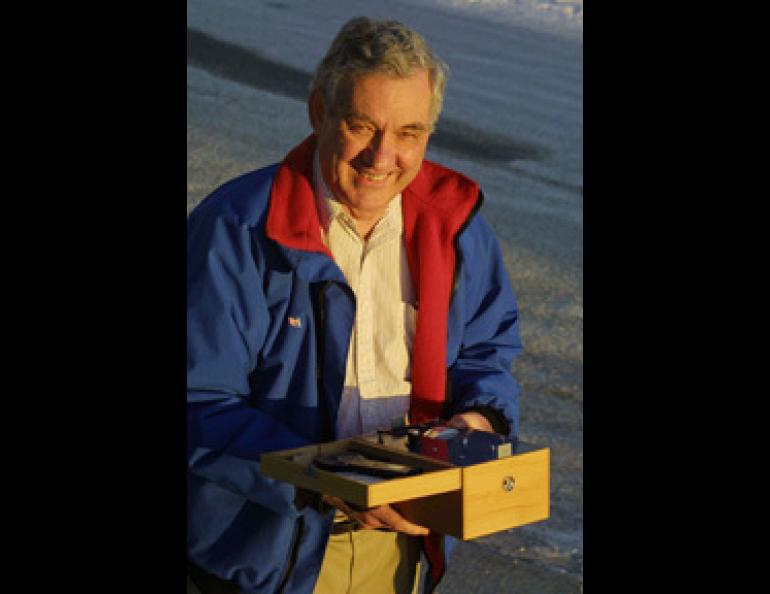

When Glenn Shaw drove from Fairbanks to Phoenix this fall, he carried along a wooden box that he pulled from his trunk every 100 miles. The box, an instrument he invented 33 years ago, tells him the quality of the air. During his late August and early September road trip, he used it to sample the air in a paved line across western North America.

Shaw is an atmospheric chemist and physics professor at the University of Alaska’s Geophysical Institute. His recent trip from Alaska to Arizona was not one of his funded studies. His research vehicle was a Toyota Corolla that Shaw and his wife Gladys drove south on a trip to visit family. He took along his wooden box out of habit and curiosity.

The box, also known as a sun photometer, is the size of a child’s lunchbox. On top is a circular peephole. When Shaw points the box at the sun, the photometer tells him how much stuff is floating in the air between the box and the sun. That stuff includes smog, water vapor, wildfire smoke, soot, and other material that blocks sunlight.

Shaw made the box when he was a graduate student at the University of Arizona in 1968. Since then, he has carried it all over the world. He has sampled air in Delhi, India, where the exhaust was so thick he could taste it. At the South Pole, he found traces of sulfur that mystified scientists until they determined it came from natural sources, such as plankton and volcanoes. When he came to Alaska in 1971, he carried his sun photometer to Barrow. There, hundreds of miles from smokestacks and paved roads, he expected to find the purest air of all. Instead, he discovered a blob of polluted air over Barrow named arctic haze, which migrates over the pole in springtime from factories in Russia and Europe.

Pulling off the road at random spots on his recent 3,000-mile trek from Fairbanks to Phoenix, Shaw pointed the photometer at the sun and recorded his findings in a logbook.

Leaving Fairbanks in August, Shaw found particulates in the air blocked five percent of possible sunlight, which means Fairbanks air was very clean.

As Shaw traveled down the Alaska Highway, he noticed a spike of dirty air outside Edmonton, Alberta. His little box measured similar particles as he traveled down the Canadian Rockies and all the way to the Idaho/Montana border. The culprit was smoke from wildfires in Washington and Oregon that was still lingering in the Rocky Mountain air.

Entering Salt Lake City, Shaw pulled over and sampled particulates from car exhaust and other urban sources that prevented 20 to 30 percent of the sun’s light from reaching his photometer.

Once he left Salt Lake, Shaw drove south through what he calls “John Wayne country,” the parks and canyonlands of southern Utah. Cresting a remote pass on Route 20, near the town of Hatch, Utah, Shaw pulled out his photometer and measured the cleanest air of the trip. The air there, at about 7,000 feet elevation, blocked less than three percent of the incoming sunlight.

“It was hyper clean,” Shaw said.

Crossing the border into Arizona, Shaw continued to measure clean air until he reached the outskirts of Phoenix. There, his little box measured the dirtiest air of the trip, which was more the five times worse than Fairbanks air.

Though the air around two of the American west’s largest cities held much more particulates than Alaska air, it was still safe to breathe, Shaw said, and it was much cleaner than the dirtiest air he had ever measured on his box. That honor belongs to Fairbanks, during a summer day a few years ago when fire smoke clogged the Tanana Valley.