Satellites now Common Objects in Night Sky

Only two decades ago, it was a thrill to see a bright, star-like object move silently and purposefully across the sky to fade out of sight well above the far horizon. This was particularly true if you knew that it was a man- made earth satellite that you were watching.

Now, on a clear, dark night, a serious observer is almost guaranteed to see at least two or three during an hour-long period.

According to the September, 1983 issue of National Geographic, between 1957 and the end of 1982, over 3000 payloads had been boosted into orbit of which about 70% have since fallen back to earth or burned up in the atmosphere. But these figures are only the payloads, and do not reflect the boosters and other miscellaneous pieces of debris in orbit which can be sighted from the ground. A preponderate amount (over 98%) of the orbiting material has been launched by either the U.S. or the U.S.S.R.

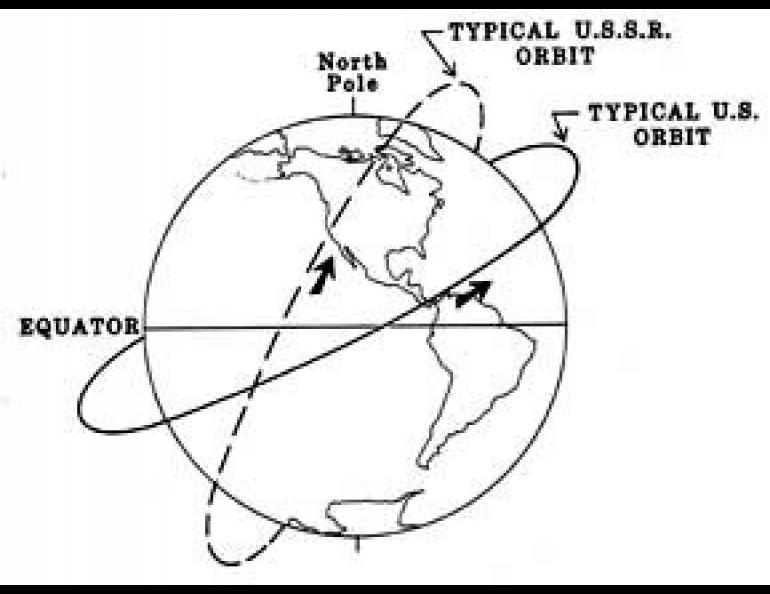

In Alaska, when you see a satellite passing overhead, it's probably a pretty good guess that it belongs to Russia. That is not paranoia speaking--it has to do with the principles of orbital mechanics. Because of factors dealing with the differences in latitude between the launching sites, it is more practical for the U.S. to put their satellites into orbit more directly to the east, while the Soviets are favored with a more northerly launch.

For that reason, most U.S. satellites orbit closer to the equator than do the Russians', which orbit closer around the poles. Therefore, for northerners, the Russian satellites are the most visible, although the opposite is probably true for those living in Florida.

One fairly reliable indicator of the nation of origin of a satellite is that it is probably American if it is traveling from west to east (it is extremely unlikely that you will ever see one traveling from east to west. This is against the earth's rotation, which gives the satellite an initial boost of about 1000 mph when launched to the east.)

On the other hand, if you see one traveling in a more north-south (or south-north) direction, the odds are that it is Russian. But there are exceptions to this. Sometimes, the U.S. puts satellites in nearpolar orbits, too, depending on the mission. For instance, the LANDSAT earth-mapping satellites operated by NASA cross over Alaska from south to north in an orbit passing nearly over the poles.

Satellite-watching can be a fascinating pastime. One night in early Autumn, I pulled off the road near Cantwell on a trip to Anchorage and lay down in the back of the pickup to stretch out for a while. In a half-hour, I spotted four satellites passing over from north to south--almost certainly Soviet. The most interesting aspect was that two of them seemed to be playing follow-the-leader in what must have been almost identical orbits. They were separated by, in the parlance of those without a more accurate measuring device, only about "three fingers" (a "finger" being the angular separation subtended by a finger, when sighting with your arm held out at full length). Was I watching a possible rendezvous? Or maybe it was a test of a hunter-killer satellite.

For those who would like to play the game of satellite-watching, there is one sure way to distinguish them from aircraft. Although you almost never notice them until they're nearly directly overhead, if you watch them long enough (a minute or two), they gradually disappear from sight without ever seeming to get even close to the horizon.