Solar Heating

It is easy to see how solar heating can be economical at low latitude. But will it work in Alaska and Yukon?

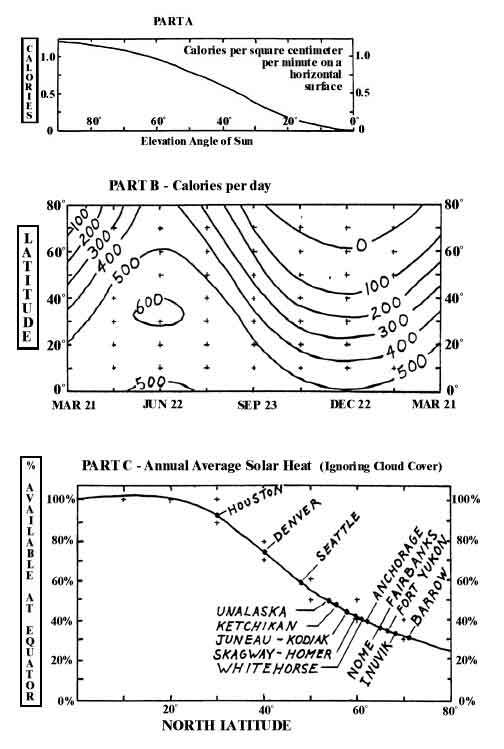

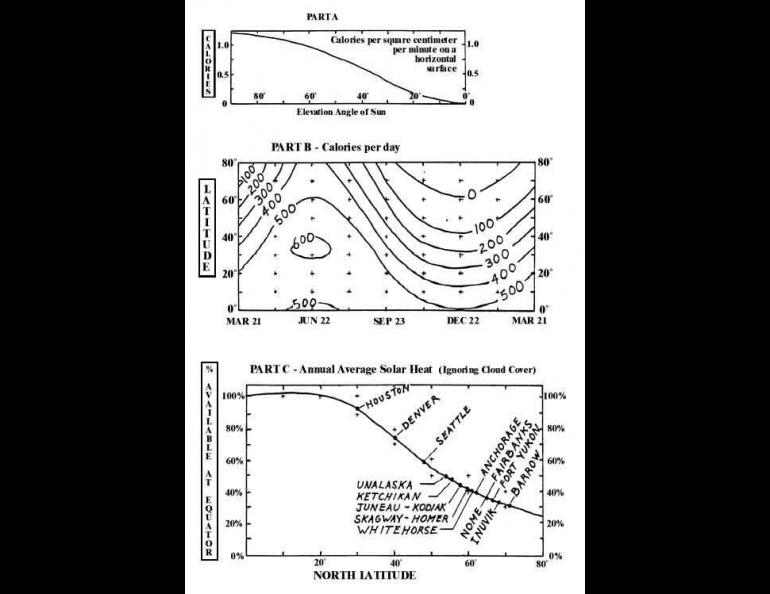

The solar energy available to a collector depends mainly upon the time of day, the time of year, and the latitude of the collector since each of these three geometrical factors determines the angle to the sun. The most possible heat is presented to a horizontal surface when the sun is directly overhead.

As the sun falls lower in the sky, there is less heat energy available for two reasons. First, there is the loss to the shielding atmosphere, and second, the energy that does penetrate through the longer path of air is spread over a larger area, just as is the shadow of any object.

Part A of the diagram shows how the number of calories per square centimeter of surface per minute drops from 1.22 when the sun is overhead (90° elevation) to zero when the sun is on the horizon. This graph does not account for any cloud cover or excessively water-laden air, both of which will reduce the amount of solar radiation reaching the earth's surface.

Part B of the graph gives contours depicting the number of calories available to a square centimeter of horizontal surface each day at locations between the Equator and 80°N. As one expects, the graph shows that at latitudes north of the Arctic Circle (66 1/2°N) solar heating is a complete bust in midwinter--the sun does not even come up. However, in summer, the high-latitude regions to receive solar energy in an amount comparable to that received at the Equator.

A comparison of the sunlight available for house heating at the different latitudes is shown in Part C of the graph. Although the annual solar energy available to the latitude region covered by Alaska and Yukon is only about one-third that available to the Equator, the amount is still substantial.

Even considering cloud cover in the interior portions of Alaska and Yukon, it is evident that more sunshine falls on the roof of a house each year than is needed to heat the house for the year.

The problems then come down to how to collect the solar energy and how to store it. Especially the storage problem is more difficult at high latitude, ant neither problem has an easy solution. Nevertheless, solar heating definitely is a practical possibility for heating northerners' homes. It seems most likely that solar heating will serve mostly as a source auxiliary to other methods. But, who knows? Perhaps as our technology improves, solar heating might take over completely.