The Spring Melting Process

The increasing hours of sunlight in March and April inaugurate one of the most pleasant processes in the northland. It is the transformation of a white world of snow and ice into one of water and greenery. The melting process begins with a tentative and nearly unseen activity, proceeds through a state of serious business, and culminates in an onrush of furious and sloppy abandon.

If undisturbed, the bright snow is highly reflective to sunlight. Until something tarnishes the whiteness of the snow's surface, the sun's heat is reflected back through the atmosphere and is lost into outer space without having done much to warm the earth, its atmosphere, or its inhabitants.

This was brought home to me while I was watching the dogsled races along Second Avenue on a windless, sunny day in Fairbanks recently. I had chosen my position in the sun on the north side of the street, although the street itself was in the shadow of buildings on the south side. Even though I was standing in the sunlight, the chill of the air (at 10 degrees) was noticeable.

Moving a half block to the east I was opposite a parking lot on the other side of Second Avenue. Hence there were no building shadows in the foreground and immediately I felt much warmer. There was no change in my exposure to the sun or in the air temperature, but here the snow in front of me was totally sunlit so it could reflect the sun toward me. It made a world of difference. The snow was indirectly warming me without absorbing any heat itself.

As long as snow remains bright, the sunshine bounces off and is not retained to cause any melting. Two factors other than sunshine which directly spell the demise of snow are air temperatures above freezing and contact with dark material that absorbs the heat of the sun. Early in the spring, the air temperatures usually are not significant in the melting process, so sunshine by itself does little to deplete the winter's accumulation of snow. But if you sprinkle some ashes, sand or other dark material on the snow, within a few days the snow will start disappearing.

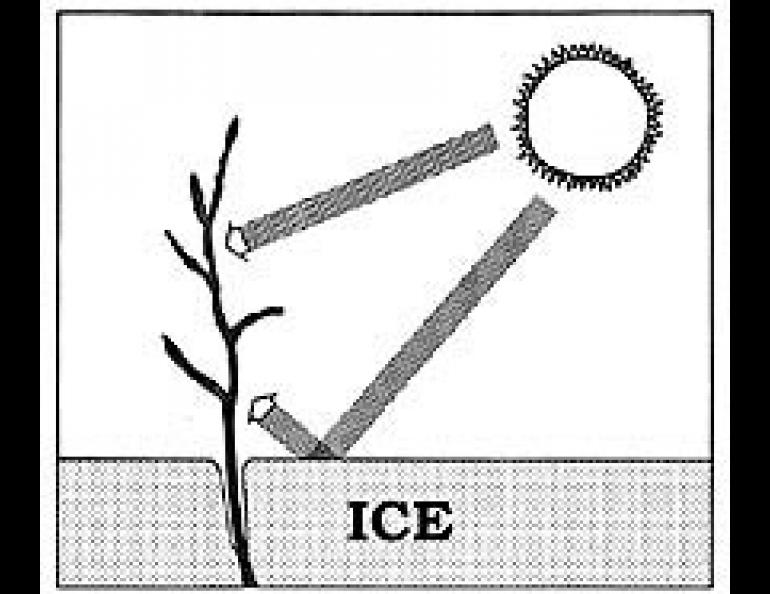

At this time of year, it is easy to see evidence of snow or ice melting indirectly from foreign material. If you look at low shrubs embedded in the ice on a stream, you will notice that each shrub protrudes through the ice via a tapered hollow core. Obviously something has melted the ice a short distance around each wood stalk. Dormant plants (and growing ones as well) produce far too little heat to melt the ice in this fashion.

The process that explains why ice melts first around the stems of plants which extend through the ice lies in the combination of direct and reflected solar radiation falling upon the shrub stems. Shrub bark is quite dark and readily absorbs much of the sun's energy rays rather than reflecting it. Like the extra warmth we feel when standing in a field of snow on a sunny day, the stems are warmed both by the direct sun as well as the radiation reflected off the nearby snow and ice.

The stems are conductors of heat, so the heat is carried downward and outward to the ice, prematurely unlocking its tight grip. After a time, this process pumps enough heat into the ice surrounding each stem to riddle the ice with holes.

Streams with shrubs growing through their cover of ice should experience a less violent breakup process in the spring owing to the general weakening of the ice around each stem.