On the trail of the snow-eater

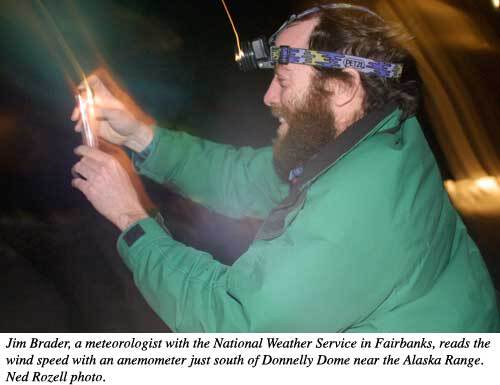

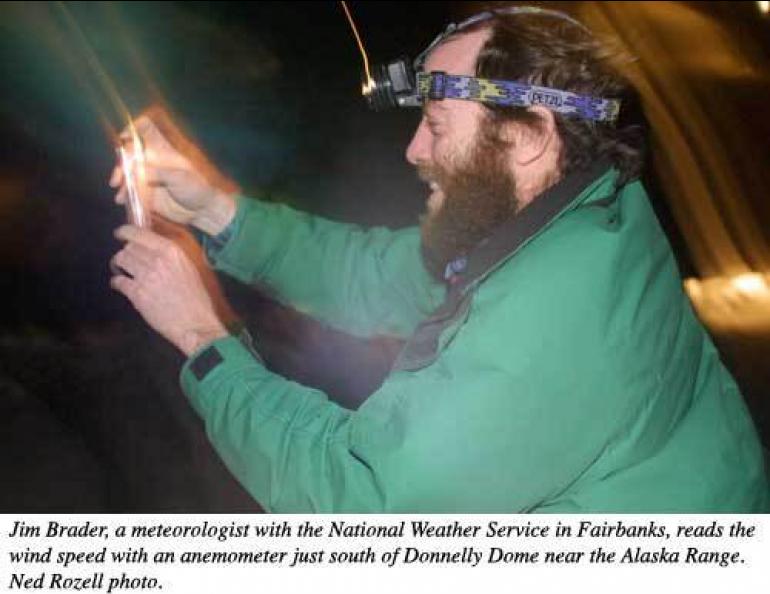

South of Donnelly Dome at midnight, Jim Brader pushed open the pickup door. He turned on his headlamp and pointed a wind gauge into a gale that sounded like a freight train. Brader, a National Weather Service meteorologist, yelled out:

“Gusts to 42 miles per hour at eye-level, probably 50 or 60 just above our heads.”

Brader had found the heart of a chinook—a warm, dry wind that floods Interior Alaska several times each winter, often driving temperatures 40 degrees warmer than average.

Chinook is a Pacific Northwest Indian word meaning “snow-eater.” The strongest chinook recorded in Fairbanks ate most of the town’s snow in early December 1934, when temperatures rose above 50 degrees Fahrenheit for five straight days.

Chinooks happen anywhere winds force moist air over a mountain range. As the air meets a mountain range, the air rises, cools, and often dumps its moisture as rain or snow on the windward side of the mountains. As the air tops the mountains and flows to the other side, it compresses the air mass below, heating up air molecules at a faster rate than they cooled going up the other side. The result is a dry chinook wind.

On a January day a few years ago, Brader showed me a satellite image on a computer: a curve of clouds pointed from Hawaii to Alaska. The clouds showed a shift in the jet stream, a high-speed current of air over the Pacific Ocean. The jet stream was steamrolling north to Alaska, carrying warm, moist air from the surface of the 70-degree ocean surrounding Hawaii. When the air hit Alaska’s mountains, the chinook would begin.

Brader suggested the best way to observe the chinook would be a drive south from Fairbanks through the Alaska Range, taking temperatures and wind speeds along the way.

We began our chinook hunt at 8:18 p.m. in Fairbanks on a dark January night. We strapped a thermometer to the passenger-side mirror of my Nissan truck, and Brader carried a pocket wind gauge.

As we pulled away from Fairbanks, the temperature at the University of Alaska’s International Arctic Research Center was 29 degrees Fahrenheit. Less than one mile later, the temperature was 16 degrees. Warm puffs of wind, the breath of the chinook, caused the temperature discrepancies, Brader said.

We drove south into the Tanana Valley along the Richardson Highway; the closer we got to the Alaska Range, the stronger the wind.

At 11:15 p.m., bursts of wind rocked the truck as we passed trans-Alaska pipeline pump station 9, south of Delta Junction. Brader turned on his headlamp and gave thermometer readings, which changed by the second as warm gusts of air pummeled the truck:

“Thirty-six, 38, 40 . . . 41,” he said.

The average temperature in Delta for January is minus 4. We drove further into the warm embrace of a chinook.

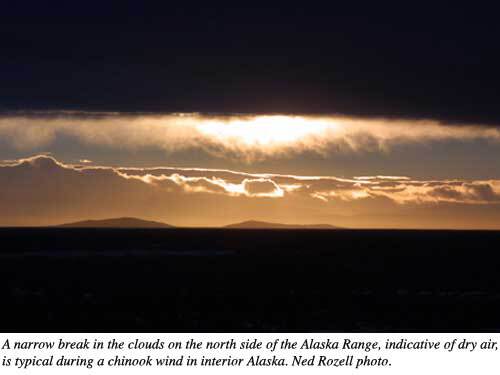

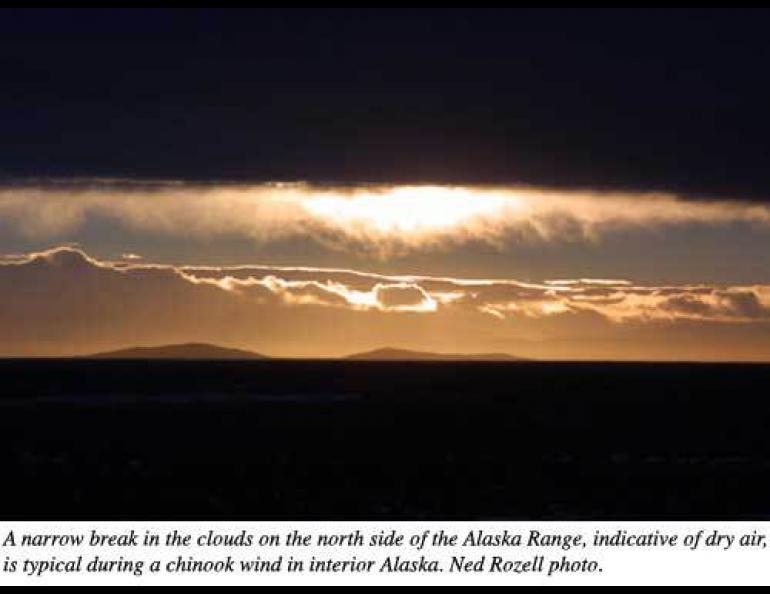

As we neared Donnelly Dome, Brader noticed Orion’s belt. The sky was clear for the first time since we left Fairbanks.

“That’s another feature of a chinook,” Brader said. “Skies are clear just on the lee side of the mountains, because the air is descending and drying as it warms.”

South of Donnelly Dome, we pulled over on an overlook of the Delta River, the high peaks of the Alaska Range hidden in darkness in front of us. Gusts of wind—the strongest measuring 42 miles per hour—smacked into us like unexpected shoves in a dark room.

Back inside the truck, the south wind forced me to mash the accelerator on the steep downhill to Donnelly Creek. Rogue blasts of wind caused the windshield wipers to spasm as if they would soon detach. Small pieces of gravel bounced off the windshield.

The Nissan struggled through the warm wind all the way to Isabel Pass, at 3,000 feet above sea level, the high point in the Alaska Range along the Richardson Highway. We stopped. The air was thick, with a strange stillness. At the peak of the Alaska Range along the highway, the temperature was 27 degrees, and there was almost no wind. Nor was there any fresh snow at the pass. Alaska’s coastal mountains must have intercepted all the wetness from Hawaii, Brader said.

“It looks like most of the moisture’s been rung out on the Chugach Range.”

At Summit Lake, winds were again calm, and the temperature was 29 degrees. We got out of the truck and stretched our legs. We had chased the chinook for five hours and 180 miles. It was 1:30 a.m. when I turned the truck around and let the warm wind blow us back to Fairbanks.