Unhealthy fats arrive with other changes in Native culture

Over the years, medical researcher Sven Ebbesson has made about 7,000 house calls in Eskimo villages touched by the waters of the Bering Sea. Ebbesson spends time in village homes because he is curious as to why diabetes and cardiovascular disease are on the rise among Alaska Natives.

“Until about 40 years ago, there was essentially no diabetes among Eskimos in Siberia, while their kissing-cousins in Alaska seemed to have a lot of it,” said Ebbesson, former director of the Alaska-Siberia Medical Research Program and a professor emeritus with the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Ebbesson launched a study in 1992 and found what he believes to be the downside of the prosperity that came with Alaska’s statehood and oil wealth.

“Until 1970, there was basically no diabetes or heart disease in Eskimos,” Ebbesson said. “It’s probably related to diet more than anything else, and the driver of the changes was income. They started to get some cash so they could buy food, and the consumption of store-bought food went way up.”

Some of those foods, especially butter, Crisco and other vegetable shortenings, and bacon fats, have over time replaced healthy fats from fish and marine mammals, Ebbesson said.

“They were always hooked on fats, because they got most of their energy from healthy fats—seals, whales, and fish,” he said. “Their diet was only 10 percent carbohydrates before. Now, about 50 percent is carbohydrates from store-bought foods.”

A few years ago, Ebbesson and his colleagues worked with 454 Natives in Norton Sound villages on an “intervention study” to raise awareness of the importance of eating good fats rather than the saturated fats found in some store-bought foods barged in from the Lower 48. In one village of 550 people, the researchers discovered that the stores sold 432 pounds of Crisco, 480 pounds of butter, and 180 pounds of margarine in one month.

“We’ve found people who have at times eaten a third of a pound of vegetable shortening each day,” Ebbesson said, noting that some people spread it on crackers and bread. It is also now a major ingredient in “Eskimo Ice Cream,” a mix of fat, sugar and berries, replacing the traditional caribou or reindeer fat.

During the intervention study, Ebbesson measured fats in people’s blood plasma and found that people who were developing diabetes had lower concentrations of omega 3 fatty acids and higher concentrations of palmitic acid associated with unhealthy foods. He designed a study to encourage people to get more exercise, quit smoking, eat traditional foods, and cut down on saturated fats and sugar.

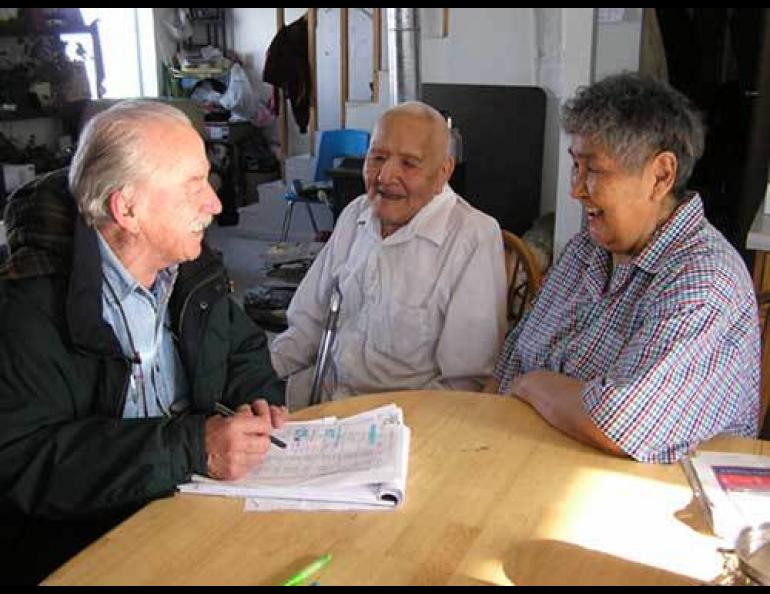

Born in a small village in Sweden, Ebbesson found that advice to substitute olive oil and canola oil for less healthy fats is more effective when he visits a place many times.

“People in villages communicate differently with each other than in New York City,” he said. “Everything is based on personal trust with one another.”

After years of sleeping in medical clinics, and visiting people in their homes, Ebbesson said he has seen results from some of his research. His intervention study seems to confirm that saturated fats contribute to the development of diabetes, and that changes in diet improve risk factors for both diabetes and heart disease. But he said the real joy is hearing from people who say their lives have improved since he first visited them.