Visit to a Frozen Planet

Late in August, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is throwing a party. It will be a broadcast celebration of a successful mission, with lots of information available. Alaskans are invited, but the guest of honor will be 2784 million miles away---only images of the planet Neptune will attend.

The pictures will be provided by Voyager 2 (and, if all goes well, relayed to Alaska from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California through the Aurora 1 communications satellite). NASA's little spacecraft will come within 4,850 kilometers (about 3000 miles) of the planet on August 25, passing over Neptune's north pole. That's a close pass in planetary exploration--closer than Voyager 2 has come to any other body during the 12 years since it left Earth.

If planets had personalities, little-known Neptune would be classed as very shy. Appropriately, its existence was predicted by a shy person. John C. Adams, a mathematics student at Cambridge University, was convinced that another large body was responsible for oddities in the orbit of the planet Uranus. In 1842 he began the difficult calculation of where that body was to be found. In September 1845 he asked the Astronomer Royal and the director of the Cambridge Observatory if they would have someone look at the area of the sky in which he believed the new planet would lie. They did not take young Adams seriously, and ignored his request. He accepted their decision.

A year later, the famous French astronomer Leverrier completed the same calculations and came up with the same location. He was taken seriously, and on September 23, 1846, the German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle followed his directions and found Neptune. He and Leverrier got the credit for discovering the new planet.

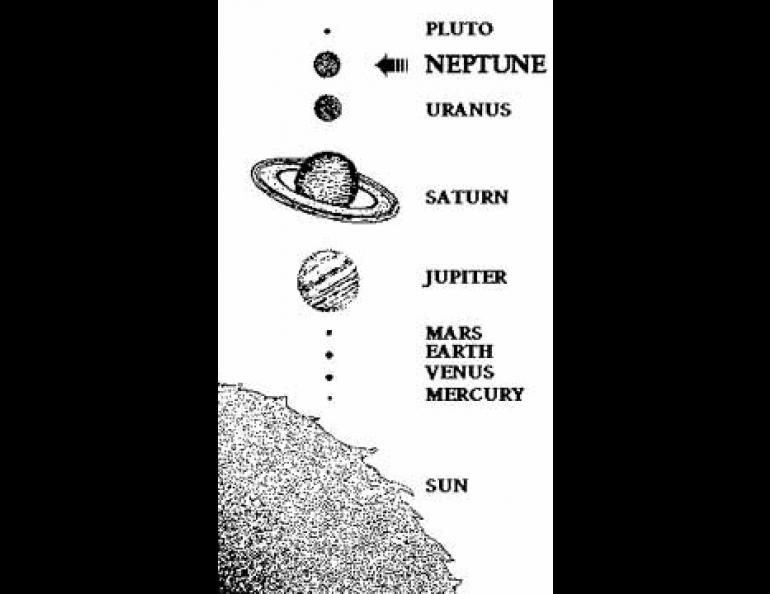

Neptune is a big planet; its diameter is about 28,000 miles (Earth is about 7900 miles in diameter). It was hard to find because it is both distant and dim.

Because it is so far away, it looks from Earth only a bit larger than Ganymede, the largest moon of Jupiter. All planets appear to shine because they reflect light, but Neptune doesn't have much to reflect. At its distance from the sun, it receives only about a thousandth of the sunlight striking Earth.

Probably none of that light penetrates through the planet's thick atmosphere to its surface---if it has what we would consider a surface. The planetologists' working models assume that Neptune has a core of rock and iron, a massive frozen layer of water, ammonia, and methane ices, and a gaseous envelope above that containing hydrogen and methane. They haven't been happy with that model, though, because it doesn't match well with the few physical aspects of the planet they've been able to measure.

They are at least sure Neptune's atmosphere contains methane. That gas gives the pale bluish-green color the planet shows when seen through a telescope, the one feature making this frozen world an appropriate namesake of the Roman sea god. Up to now, no one has been sure even of how long Neptune's day is. From its changing patterns of reflectivity, Neptune's rotation period has been estimated variously at 18 hours, 15 hours, and near 14 hours.

The NASA television broadcasts will be on the air from August 21 through 29. Check with local stations for show times; if you have your own satellite dish, you should be able to find the broadcast between 4 p.m. and midnight (Alaska time) from Aurora 1, transponder 21. Experts from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory will provide explanations and background, but the raw images will have the starring role.

The instrument array aboard the spacecraft will uncover Neptune's mysteries at a phenomenal rate. In fact, as the information comes pouring in, anyone who follows the daily news--much less the special television broadcasts that NASA has arranged--will know more about that giant planet by September than any scientist on Earth knew at this time last year.