Whalers may have triggered killer whale diet shift

Killer whales have teeth that are three inches long, pointy, and unlike any other animal alive, but similar in size and sharpness to the teeth of Tyrannosaurus rex.

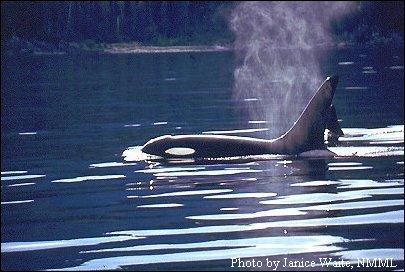

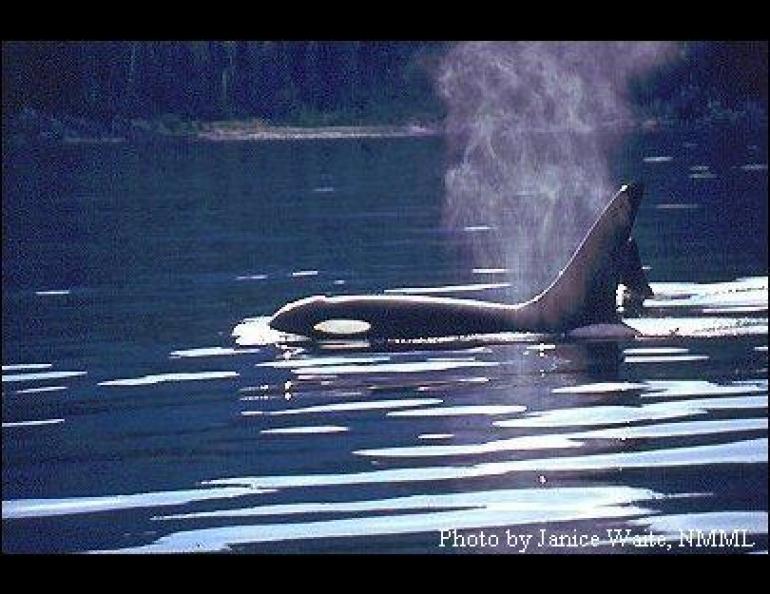

These perfect predator teeth help support the idea that killer whales are eating more sea lions, seals and sea otters, and that humans are behind a drastic change in the northern Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea ecosystems. During a recent lecture in Fairbanks, oceanographer Alan Springer presented an argument that industrial whaling in the mid-20th century caused a chain of events that has led to declines of marine mammal populations in Alaska waters.

Springer’s colleagues, including Jim Estes of the Center for Ocean Health in Santa Cruz, California, made headlines in 1998 when they claimed that killer whales were behind a population crash of sea otters living in the Aleutians and Bering Sea in the 1990s. Now the researchers are going a step further by arguing that after Japanese and Russian whalers removed at least one-half million great whales from the North Pacific Ocean and southern Bering Sea between 1949 and 1969, killer whales were forced to hunt other species, such as Steller’s sea lions, fur and harbor seals, and sea otters.

Springer, a research associate professor at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Institute of Marine Science, showed a slide of a killer whale tooth next to a Tyrannosaurus rex tooth to demonstrate that, like the king of the dinosaurs, the killer whale has evolved to eat huge animals, such as great whales. Great whales include blue, bowhead, gray, fin, sei, and sperm whales.

After World War II, Japan and the former Soviet Union found a use for military gunboats by turning them into industrial whaling ships. The whalers started off the northern coast of Japan, and they later followed the whales into the waters of the North Pacific and southern Bering Sea surrounding Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, and eventually the Gulf of Alaska. By the mid-1970s, great whale populations in the North Pacific and southern Bering Sea dropped, and today are about 14 percent of pre-whaling levels, the researchers wrote in a recent paper.

“(Industrial whaling) was extreme, no doubt about it,” Springer said. “It left a great void out there.”

The lack of large meals in the form of giant whales may have led killer whales to feed on other, perhaps less desirable, food sources. Springer and his colleagues think the killer whale is behind historic declines of Steller’s sea lions and sea otters, and the current falling numbers of northern fur seals and harbor seals. These creatures don’t have much defense against a killer whale, known as an “apex predator” because nothing exists above it in the ocean food chain.

Above the ocean’s surface lurks the ultimate apex predator, the human being. Springer said that with industrial whaling, our species triggered changes in the northern marine ecosystem that trickle down all the way to an overabundance of sea urchins that are consuming kelp forests, leading to the loss of those communities because not enough sea otters exist to keep the urchin population down.

More often than not, scientific studies leave researchers with more questions than answers, but Springer said the recent disappearance of marine mammals in Alaska waters due to industrial whaling and a shift in killer whale predation might be a slam-dunk.

“If you take too much of anything from a system, you mess things up,” he said. “In this case, the best explanation is the one that’s the simplest.”