Where the Oil's Going---and Why

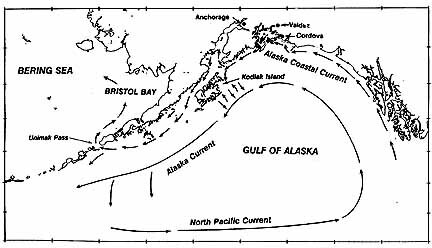

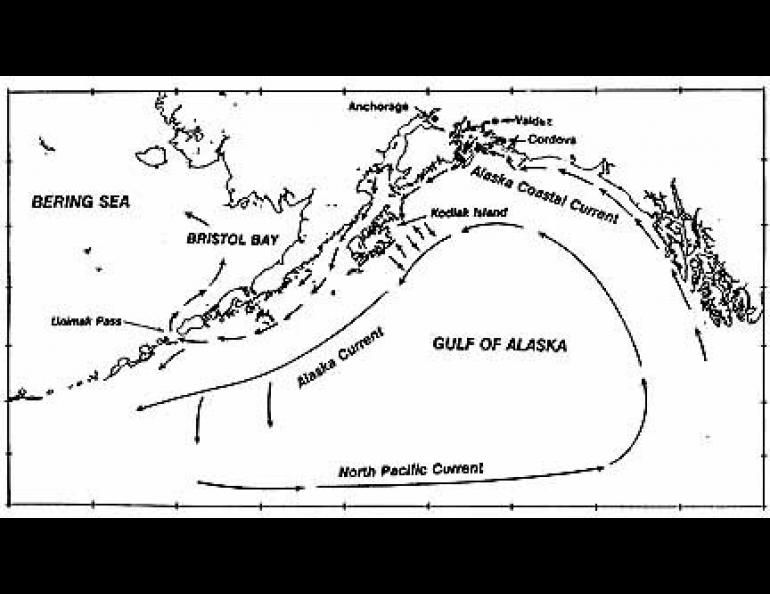

Oil spilled from the Exxon Valdez could be setting out on a very long voyage, propelled in good part by fresh water. The oil is carried along in the Alaska Coastal Current, a stream of low-salinity water flowing like a river within the sea.

The current begins with the heavy precipitation in British Columbia and southeastern Alaska. As the freshwater runoff discharges into the sea, the effect of the earth's rotation turns it to the right. It flows northward along Southeast's coast, gathering more fresh water as it goes. Less dense than seawater, the freshwater flow resists mixing into the ocean.

Though too salty to drink, Coastal Current water stays less saline than the surrounding sea, making a fresher, identifiable stream. Some of the runoff comes from glacial streams laden with fine sediment; the sediments carried along in the current are visible in aerial and satellite images, acting as another tracer for the current's flow.

As the current flows northwestward along the coast into the northern Gulf of Alaska, it picks up still more fresh water. Prevailing winds from the east push the current toward shore; generally it stays in a band of 5 to 15 miles from the coast. Its speed varies from half a knot (nautical mile per hour) at this time of year to more than three knots in fall, the time of greatest runoff. In spring its flow rate is about 50 million gallons each second; over the course of a year, the average freshwater runoff into the current is about 1.2 times the average annual discharge of the Mississippi River.

Most of this current swings into Prince William Sound, entering from the east through Hinchinbrook Entrance and pouring out through Montague Straits to the west. (In fact, the sound may be thought of as a kink in the Alaska Coastal Current rather than a closed waterbody.) That is why the oil spilled at Bligh Reef has progressed westward out of the sound.

The same flow-through action will flush the sound's waters, but this oceanographic cleaning moves unevenly. By mid-April, little oil remained in local offshore waters, but enclosed bays and shorelines fared less well. Because the water moves more swiftly in the upper layers, the deep water (in some places, more than 1000 feet deep) will cleanse itself more slowly. We know the deep waters are usually renewed each fall, and we will be monitoring the process closely this year.

Fall rains will speed the flushing action, as the coastal current accepts the year's heaviest precipitation. Waves from winter storms will pound the exposed coasts, probably finishing the cleanup there but doing less for protected shores.

Once out of the sound, the oil continues west with the current along the Kenai Peninsula. Easterly winds keep it close to shore; a strong low-pressure system could push it onto shorelines and into fiords. Near Kodiak Island, both the easterlies and the freshwater discharge diminish. Now both the coastal current and the possible paths for the oil become more complex.

One arm of the current swings into Cook Inlet, while a nearly equal part flows southward along the eastern shore of Kodiak Island. In Cook Inlet, the current splits again, part going north and part heading along Shelikof Strait, the probable source of oil at Katmai National Park. The north-flowing portion follows the eastern shore of the inlet until, joining the freshwater discharge from the upper end of the inlet, it loops back south and also enters Shelikof Strait.

The current passing east of Kodiak Island enters an area of little net flow, because the winds are variable and the freshwater discharge is small. Oil getting there can stay for one or two months, a real concern for the Kodiak shelf fisheries.

Eventually any oil remaining in the water will be caught up in the deep southwestward- flowing current at the shelf break, which stays about 100 miles offshore. In the deep ocean, dilution and weathering should reduce the oil to tar balls. North Pacific currents will bring this water around to the Washington and British Columbia coasts in a year or less; some of it may rejoin the Alaska Coastal Current there, coming back to Prince William Sound in another year.

Oil entrained in the portion of the current passing through Shelikof Strait will be spread along the Aleutians--probably with little harm, because the winds no longer force it toward the coast--and some will be carried through Unimak Pass into the Bering Sea. The estimated time of transit from Prince William Sound through the pass is two or three months, so the spill should be well weathered and diluted by then.

Ultimately, the Alaska Coastal Current may carry some of the oil to an ironic destination. Net flow north through Bering Strait, the Chukchi Sea, and eastward through the Beaufort Sea means that sometime in the future, tar balls that began their oceanic voyage as oil spilled at Bligh Reef may wash ashore in Prudhoe Bay.