Alaska forests in transition

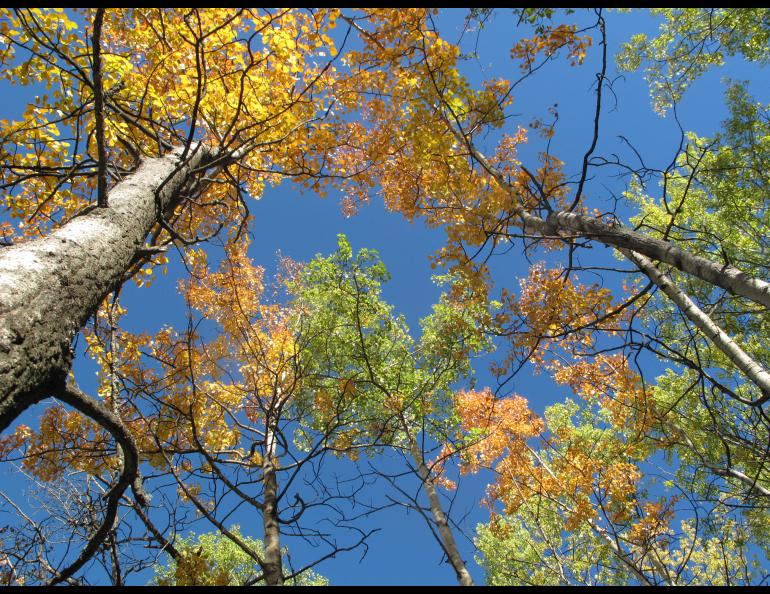

In almost every patch of boreal forest in Interior Alaska that Glenn Juday has studied since the 1980s, at least one quarter (and as many as one-half) of the aspen, white spruce and birch trees are dead.

“These are mature forest stands that were established 120 to 200 years ago,” said Juday, a professor of forest ecology at the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ School of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences. “Big holes have appeared in the stands.”

At his Dec. 7, 2012 presentation during the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union held in San Francisco, Juday spoke of a “biome shift” now underway in Alaska — the boreal forest is suffering in the Interior and flourishing in western Alaska.

Juday presented his observations of boreal forest trees on remote and road-accessible plots along the Tanana River downstream of Fairbanks and in the White Mountains National Recreation Area. He also included results from tree-coring trips he and his colleagues performed down the Tanana, Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers.

In the Interior, Juday sees significant numbers of dead trees, which he attributes to higher air temperatures here since the mid-1970s. Along with less moisture available to trees, some of the warmer temperature events have triggered infestations of insects, like the aspen leaf miner, the larva of which reduces the efficiency of leaves. Warmer temperatures have reduced other trees’ ability to produce sap, which helps prevent insect attack. The result has been trees pushed to their limits.

“The prospects are not good for survival (of white spruce, aspen and birch),” Juday said. “This overall, coherent shift is not just an unlucky break at a stand or two, but is consistent with the first stages of a serious rearrangement of forest in the landscape across northern Alaska.

“The Interior forest is likely to retreat to cooler microsites, such as shaded slopes and somewhat higher elevations,” Juday said. “Various kinds of stunted woodland, shrubland, and grassland are likely to expand where formerly our productive forest grew.”

In western Alaska, where summers are cooler and more snow and rain falls, the trees have responded to temperature increases with greater growth.

“This positive response extends out to the very western limit of tree establishment and survival at the edge of the tundra,” Juday said. “The trees there are generally healthier than they have been at any previous point in their lives.”

Juday said the current changes within Alaska’s boreal forest will probably continue unless warmer air temperatures that started in the mid-1970s return to those levels or cooler.

“The future of the Alaska boreal forest is shifting decisively to western Alaska,” he said.

* * *

Southeast Alaska trees are also reacting to recent changes in climate, said Greg Wiles of The College of Wooster in Ohio. Wiles also spoke about his research at the AGU meeting.

Using weather records from Sitka written down by the Russians as early as 1830 and later continued by Americans and comparing them to tree growth, Wiles and his coworkers have charted reactions to warmer air temperatures of mountain hemlock trees at different places on mountain slopes.

“Lower elevation (trees) are hurting, mid-elevation trees are tracking the change and high elevations are taking off,” Wiles said. “All of a sudden, conditions are right for (the higher trees).”

Alaska rainforest mountain hemlocks seem to be experiencing the same “biome shift” Juday described in Alaska’s boreal forest, Wiles said.

“These trees are adapted to the Little Ice Age,” Wiles said, referring to a cold period on Earth from about 1550 to 1850. “Now we’re out of the Little Ice Age.”

Wiles wondered if the mountain hemlocks have enough mobility to occupy new elevation niches that may be better suited for the trees.

“Is change happening faster than (these trees) can migrate?” he asked.

The Alaska Science Forum has been provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community since the late 1970s. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.