Alaska a hot topic in San Francisco

While trolling the poster sessions at the Moscone Center in San Francisco during the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting (attended by more than 13,000 scientists), a person bumps into a great deal of information on Alaska. Here are some notes from the legal pad:

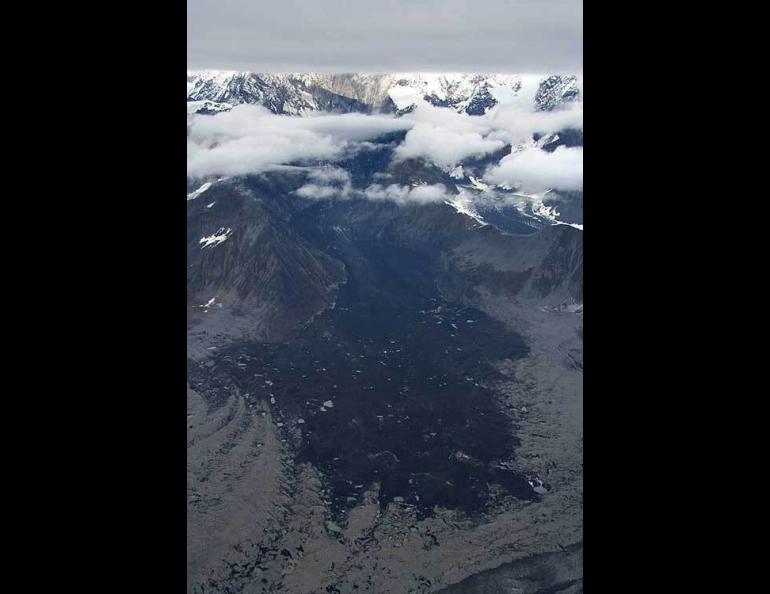

In September 2005, a massive rock avalanche on a remote mountain peak registered on seismometers all over Alaska. Earthquakes sometimes rattle steep mountains and cause avalanches, but no earthquake preceded the collapse on Mount Steller, located about 80 miles east of Cordova. A scientist may have found the trigger for the rock and snowslide that fell about 8,000 feet, sheared off a glacier on the way down, and spewed black rock that extended six miles from the mountain.

A year after the event, Bruce Molnia, a glaciologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in Reston, Virginia, was looking at aerial photos of Mount Steller and saw a hole in the surviving ice face that didn’t fall from the top of the mountain. The ice cave is the mouth of a channel that probably held running water, Molnia said.

“You don’t get 30-meter holes on top of a mountain without water flowing down,” Molnia said.

Looking at the photos of Mount Steller and nearby peaks, Molnia also saw evidence of two more water channels above other avalanche sites. Somehow, he said, large amounts of water are flowing through ice and snow at high altitudes in the area.

“(The avalanches) all seem to have an unusual meltwater trigger,” he said. “How can you get so much meltwater at 3,000 meters?”

. . .

A scientist who has monitored temperatures in and around Barrow since 2001 has found that the “urban” area of Barrow averages 2 degrees Celsius warmer than the surrounding tundra in the winter, and is sometimes 6 degrees warmer.

Ken Hinkel of the University of Cincinnati documented Barrow’s “heat island” with 70 instruments that have recorded temperatures in and around Barrow once an hour since 2001. He wanted to see if manmade warmth in Barrow had anything to do with the fact that the snowmelt date at Barrow is now three weeks earlier than it was in the 1940s.

Researchers have found heat islands in many other cities in America, but Hinkel said that Barrow is different because there are few vehicles there, which means that most of the heat measured must be escaping from buildings in winter. He also said Barrow’s heat island disappears when there are high winds, and that the town’s heat island probably results in an eight percent reduction in fuel bills during winter. As for the warmth generated by Barrow residents affecting the earlier snowmelt date, he said it was unlikely because the heat island is not as strong when the area’s snowpack is melting in the spring.

. . .

University of Alberta researchers looked at ancient permafrost at a placer mine along the Yukon River between Dawson City and Whitehorse and determined that it had survived the peak warmth of the planet’s last great warm period, which was about 125,000 years ago. Some geologists thought that permafrost didn’t survive previous warm periods in Alaska’s Interior.

“Reports of the death of permafrost in interior Alaska and Yukon during the last (warm period between glacial periods) may be greatly exaggerated,” graduate student Alberto Reyes wrote. “By analogy, deep permafrost is likely to persist in the discontinuous permafrost zone, at least locally, despite future global warming.”

. . .

Martha Shulski of the Alaska Climate Research Center at the Geophysical Institute recently tallied up the mean annual temperature for Alaska locations in 2006, and Anchorage and Fairbanks were both cooler than normal. Fairbanks was 25.8 degrees Fahrenheit, one degree colder than normal, and Anchorage’s mean annual temperature was 35.6 degrees; its yearly normal is 36.2 degrees Fahrenheit.