Alaska shrews getting larger because they're warmer?

Some of Alaska's tiniest creatures may be getting larger, and a warmer climate might be the reason, according to a scientist from Israel.

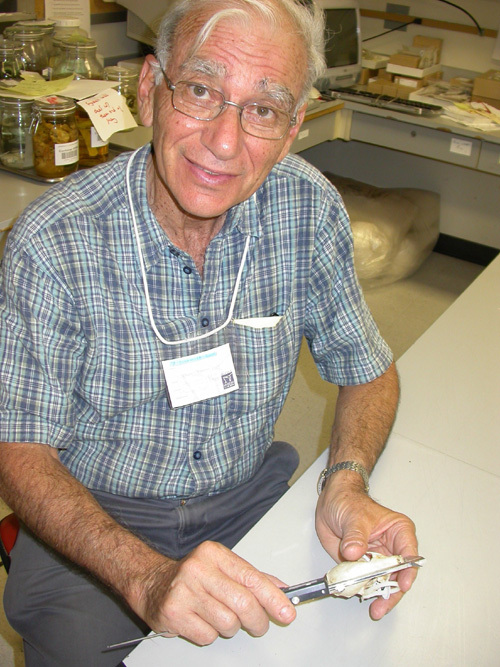

Yoram Yom-Tov of Tel Aviv University was in Fairbanks recently for a meeting on evolution that drew hundreds of his colleagues from all over the world. In his presentation, Yom-Tov said that the size of Alaska's masked shrews has "significantly increased" during the last 50 years.

He makes that claim after comparing body length and weight measurements of more than 2,000 masked shrews in Alaska that are now in the University of Alaska Museum of the North's collection in Fairbanks. The museum has skin, bones, and some frozen flesh of more than 86,000 mammals, including thousands of shrews. From his office in Tel Aviv, Yom-Tov was able to access the information about the masked shrews from the museum's website.

He found that the shrews--so small they fit in the palm of a hand--increased in body size during the last 50 years, when Alaska also got warmer. According to the Alaska Climate Research Center's data from 20 towns from Barrow to Annette, the average temperature in Alaska increased 3.3 degrees F from 1949-2003.

The larger body size of masked shrews seems to link up with higher temperatures, but that correlation goes against one of the laws of science known as "Bergmann's rule" for the man who thought it up. Believers of Bergmann's rule point out that animals from warmer places are smaller than animals from colder places, perhaps because moose stay warmer than whitetail deer for much the same reason that a cup of water takes longer to freeze at 20 below than does a thimbleful.

Yom-Tov has seen Bergmann's rule in action in Israel, where he compared hundreds of songbirds in his university's museum collection and found that they had indeed gotten smaller as Israel got warmer in the last 50 years. Looking for more examples of changes in body sizes possibly due to warming, Yom-Tov searched for museums that had specimens going back 50 to 100 years and found the University of Alaska museum, which attracted him even more because of its subarctic location and the notion that climate changes are realized first and hardest at extreme latitudes.

The masked shrew is not the first creature to break Bergmann's rule. In a 2004 study of wood mice in Japan, Yom-Tov found them to be 10 percent bigger now than they were a century ago.

Why would a creature become bigger instead of smaller in a warmer environment? Animals fighting the cold for shorter periods might be able to put resources they used to keep warm into growth, Yom-Tov said.

"In the wood mouse study, a temperature increase of 1 degree (Celsius) was roughly equivalent to a 10 percent savings in the energy required by the mice," he said. "Warming enables them to conserve energy."

Yom-Tov used his time in Fairbanks with his wife and fellow researcher Shlomith Yom-Tom to sit down with the museum's collection of marten skulls. He measured hundreds of the skulls, collected by trappers and others who donated them to the museum, and will again compare their sizes over the years to see if Alaska's marten, like its masked shrews, are getting bigger.

"Collections like this are a great historical record of the environment," Yom-Tov said.