Arctic lakes getting a closer look

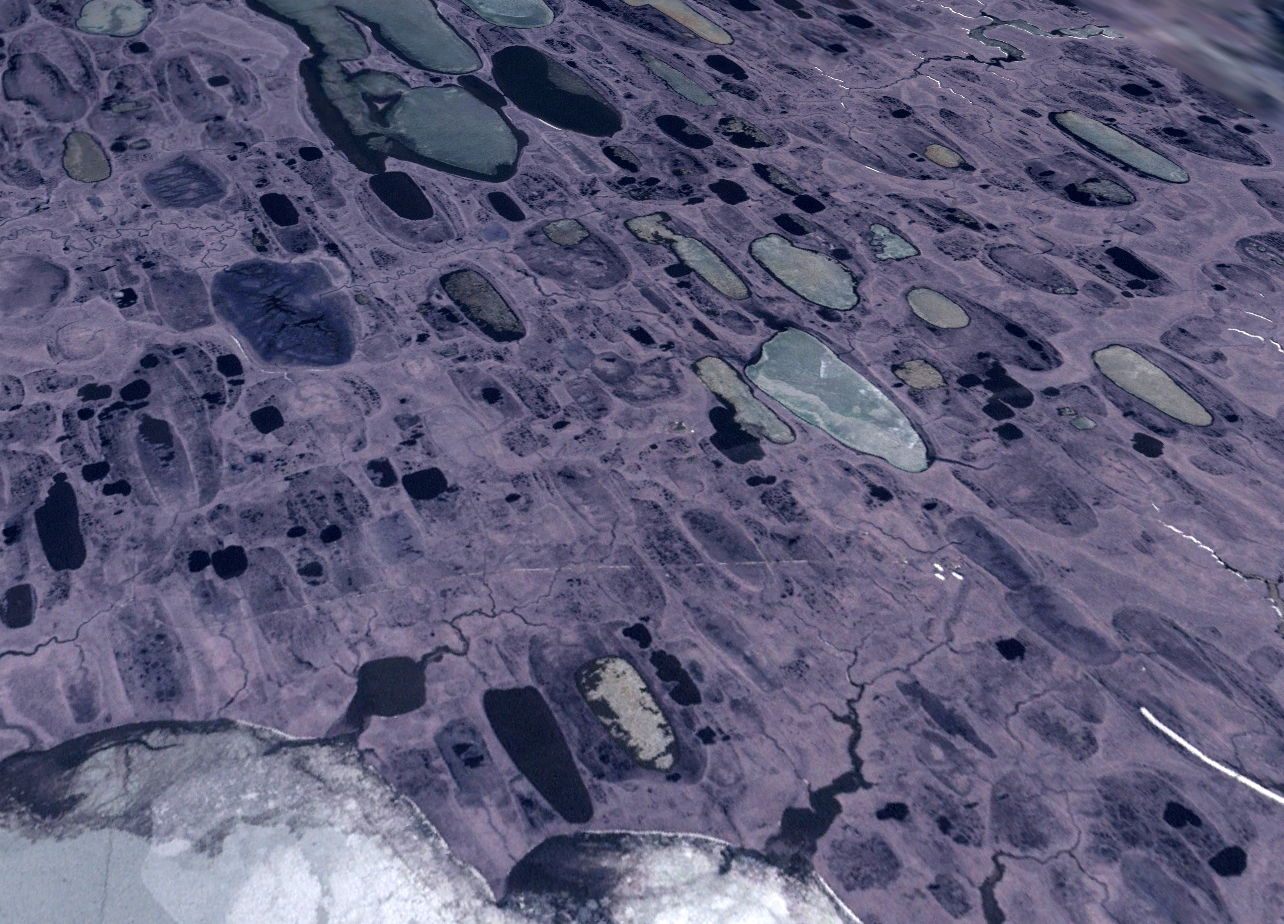

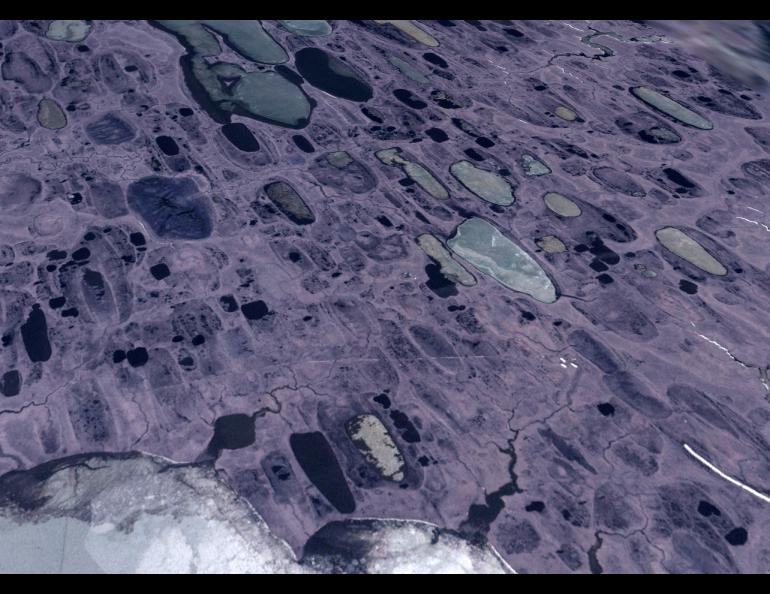

Minnesota is the Land of 10,000 Lakes, but Alaska has more than that in the great expanse of flatlands north of the Brooks Range. These ubiquitous far-north bodies of water — most of them formed by the disappearance of ancient, buried ice that dimples the landscape as it thaws — make the maps of Alaska’s coastal plain look like Swiss cheese.

A large group of scientists are now taking a closer look at Alaska’s “thermokarst” lakes, some of the fastest-changing landforms on the planet.

Guido Grosse just got back from a spring trip to a few dozen frozen lakes of the north. A permafrost scientist with the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Grosse and three partners covered 800 miles of northern Alaska on snowmachines, stopping at groups of frozen lakes in still-wintry April weather and installing instruments that will remain for years.

While Grosse’s group was breaking trail over the blown snow of the central arctic plain, another group of scientists was putting down tracks farther west, doing the same things with other bodies of water somewhat hidden under a blanket of white. The result is a large network of arctic lakes that now have weather stations on their shores, temperature-sensing and lake-level buoys that will float on the lakes once the ice goes out, and other equipment. The study will help define the character of water bodies that take up more space on the northern part of the globe than New Zealand does in the South Pacific.

The lakes range in depth from three to about 50 feet. Some freeze to the bottom, some don’t. A few have fish in them. Some of the lakes are lined up together like salmon swimming upstream. Some are round as craters.

Many of the lakes don’t lose the last crystals of winter ice until summer solstice. Helped by the summer sun, some lakes are growing by the length of a caribou each year. Others are drying up and disappearing. As they change, the lakes affect birds that nest around them, villagers who use them for drinking water and oilfield workers who use their water for ice roads. And the lakes have potential to affect much more, with the gases they are leaking.

Most of the thermokarst lakes of the north have been around for 10,000 years or more, when ground ice from a colder period of Earth’s existence thawed and left behind a depression in the tundra to gather water. Scientists were first attracted to them for their orderly appearance near Barrow (maybe caused by prevailing winds or the angle of the sun or both), but they have in recent years found the lakes to be belching measurable amounts of greenhouse gases as the permafrost thaws around and beneath them.

“There’s a significant amount of methane and carbon dioxide coming out of some the lakes; some seem to emit almost nothing,” Grosse said.

Grosse and his partners — Chris Arp and Ben Gaglioti of UAF and Benjamin Jones of the USGS — in early April began a journey from Toolik Field Station off the Dalton Highway. On snowmachines, they drove a long loop from Toolik to Umiat, Inigok, Teshekpuk Lake and to Fish Creek on the lower Colville River. Along the way, they stayed in small, established camps and installed lots of instruments on and around the lakes, all the better to discover the character of one of the most dynamic but understudied features of the Alaska landscape.

The project team, which includes scientists from as far away as the University of Cincinnati, Clark University in Massachusetts and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, will spend the next four years looking at the lakes. They hope to someday expand the network to the many arctic lakes outside Alaska, and they want to do it soon.

“These lakes change pretty rapidly even on a human timescale,” Grosse said.

The Alaska Science Forum has been provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a writer at the institute. Posted by Ned Rozell on May 24, 2012