Backyard glaciers on the wane in Alaska

On late winter nights in the Goldstream Valley north of Fairbanks this past winter, a woman named Hilary went for walks on the snow-covered trail outside her house. During a time of year when silence dominates, she heard something strange—the sound of running water.

Water was percolating up through the ice of nearby Goldstream Creek, and flowing in fan-like channels over the ice. Not long after it hit the surface, the water froze. Ice accumulated over the days until it created a small glacier that crept to within a few feet of a woodpile on Hilary’s porch. At about the same time, water began seeping into the first story of her house.

“I’m someone who appreciates nature, but there’s a certain line where what’s beautiful and awesome becomes a threat,” Hilary said.

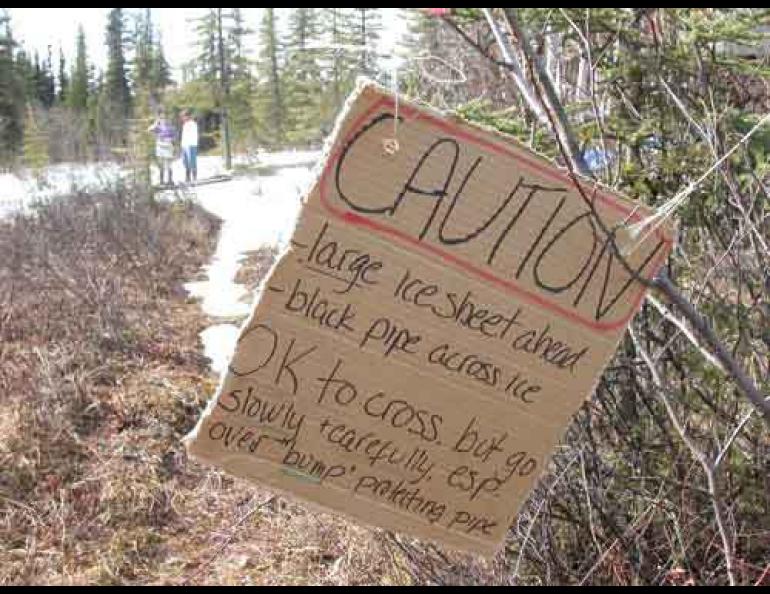

Hilary and her landlord installed a plastic pipeline to divert the water from her house. It flowed like a river back to the frozen creek and eventually slowed to a trickle. Her little glacier continued to grow until the warmth of spring finally began shrinking it. The change of seasons saved her woodpile from the ice.

Overflow ice, also known as aufeis (German for “on ice”) formed on many small creeks this winter, according to National Weather Service hydrologist Ed Plumb. He visited Hilary recently to see her glacier and interpret the scene. He said the recent winter was a prime season for creating aufeis in the Interior.

“We didn’t get much snow this year and it was cold early,” he said. “November was the fourth coldest on record, we got about an inch of snow, and it really drove the frost line down. We saw a lot of icing this year.”

Aufeis often shows up on Interior roadways where roadcuts intersect the water table. Groundwater seeps out and covers the road, freezing into small glaciers before crews with graders can scrape it away. Overflow ice occurs anywhere in Alaska, and is more prevalent in colder temperatures and in years of low snowfall where ice freezes thicker and pinches off normal channels, forcing water to the surface.

“It’s common on the North Slope,” said Larry Rundquist of the Alaska-Pacific River Forecast Center in Anchorage. “Springs that flow up there can cause sheets of aufeis that are tens of feet thick.”

On a larger scale, river and lake ice in Alaska is breaking up gently so far this year. Because of Alaska’s warm spring, the recent trend of easy river breakups looks like it may continue, Rundquist said.

“The Yukon has a pretty deep snowpack in its headwaters in Canada,” Rundquist said. “If it sends snowmelt down before the ice rots out, it could be a concern for the upper river. But most of Alaska at this point is looking pretty good. If the temperature stays above average, we could have a really easy breakup, but it’s still a little too early to say for sure.”

For the most current forecast of the spring flood potential in Alaska, go to http://aprfc.arh.noaa.gov.

***

After he read last week’s column on the decline of Alaska’s tamaracks, Bob Wheeler, a forestry specialist with the Cooperative Extension Service in Fairbanks, called to say that tamaracks and other larch trees in people’s yards have fared better than wild trees against the larch sawfly and larch beetle.

“Natural populations have been hit much harder than trees in a cultured landscape setting,” he said. “Site has a lot to do with a tree’s resistance (to insects) and (tamarack) often seek out poorer sites.”