A better look at Greenland glaciers on the go

Using some of the great datasets available today, Mark Fahnestock figured the average winter temperatures of the Arctic from the time he was born until he was 10 years old. He compared that data to the same period in his son’s life, finding the Arctic has warmed about five degrees since Fahnestock was his son’s age. All that warmth affects things, the scientist said at a recent meeting in Fairbanks.

“The glaciers are getting the message,” Fahnestock said.

As a glaciologist with the University of Alaska Fairbanks’ Geophysical Institute, Fahnestock has witnessed some of the world’s great glaciers purge colossal amounts of ice out to the sea. He showed a video clip of a massive Greenland glacier calving off half a billion tons of ice in a few minutes as he and his coworkers looked on. The transfer of ice to the sea was so dramatic it made the ground move, just a hair, in South Dakota, Fahnestock said.

Fahnestock and his colleagues have been camping near ice-choked fiords in Greenland the past few years to study the world’s fastest-moving glacier. Jakobshavn Isbrae spills about 100 feet per day into the ocean, losing more than 40 billion tons of glacial ice every year. This summer, Fahnestock and fellow GI glaciologists Martin Truffer and Roman Motyka also continued a study on a smaller Greenland glacier that is racing to the sea.

Researchers call the glacier on Greenland’s southwest coast “KNS,” because it’s easier to say than Kangiata Nunata Sermia. They wanted to study KNS because another institute in Greenland has more than 10 years of data of the fiord into which KNS calves. And, in their experience with studying Alaska tidewater glaciers, they have found that the ocean calls the shots on how much ice flows into the sea.

“Tidewater glaciers are hard to access, and all the glacier change happens right at the ocean,” Truffer said. “It’s the most interesting area, but the hardest to measure. We want to solve what happens out in the ocean to glaciers, and having a decade of information in the fiord helps with that interpretation.”

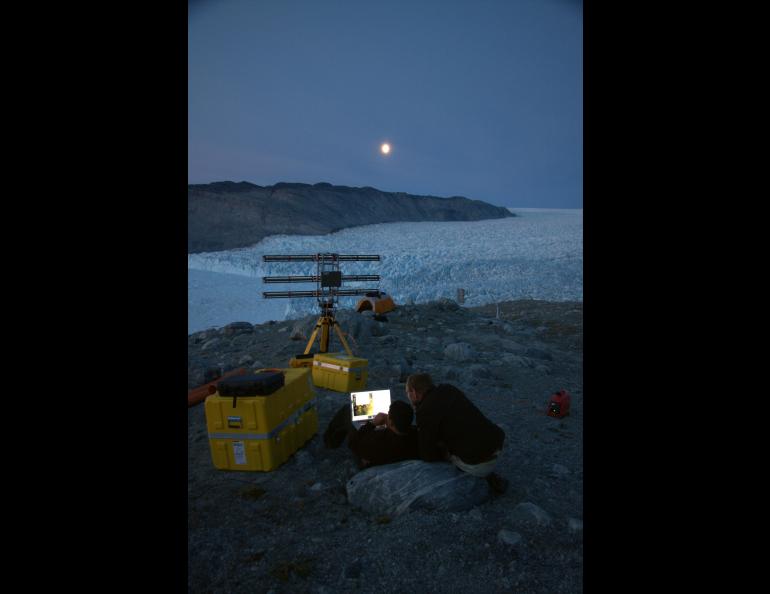

The scientists have a new tool for measuring the vast area where ice splashes into the ocean. They have deployed a ground-based radar system that sits on a tripod and is about as tall as a glaciologist. The radar sweeps back and forth out to as far as six miles away, allowing them to see changes of the glacier as well as the ice in the fiord at the same time. With the radar, the scientists can make detailed images that look like video of the moving glacier and the ice in the fiord.

“It’s really phenomenal,” Truffer said of the radar, which inventors developed for a better look at slow-moving landslides. The radar uses what’s called an “interferometer” to find changes between antenna rotations. Satellites carrying similar instruments have been orbiting Earth and sending down images useful to glaciologists for quite a while now, but satellites with that technology don’t repeat a pass over an area for several days; the ground-based radar system gives the glaciologists images as often as every two minutes.

“You can measure what you want rather than wait for satellites,” Truffer said.

Next summer, the team will bring their new radar system to Jakobshavn Isbrae for a better look at the world’s speediest glacier. Closer to home, they will also use the radar in collaboration with a permafrost researcher to gain a better look at a mountain of rock, ice and trees that is flowing toward the Dalton Highway north of Coldfoot.

This column is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.