Bird havens on a trans-continental journey

Right about now, songbirds in Brazil are shifting on their perches, feeling mysterious impulses that will soon make them leap off their branches and head toward Alaska.

One of these birds is the olive-sided flycatcher, about as tall as your hand, with a blocky body and head. With good fortune, these birds will in a few months be fluttering into a forest swamp in Alaska, Canada or the Rocky Mountains, with a mission of replicating.

Julie Hagelin has pulled on her Xtratufs to visit spruce wetlands in Alaska in search of the olive-sided flycatcher. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game biologist is co-author of a recent paper in which she and her colleagues have identified important areas that flycatchers from Alaska use when they leave each fall.

The olive-sided flycatcher has a memorable song, the males singing “quick, three beers!” to attract a mate. They have one of the longest migrations of any North American breeding songbird — up to 7,000 miles one-way each spring and fall. Mated pairs of the birds don’t produce very many chicks (from two to four), and the birds live a long time (a tagged bird reached 11 years old).

And — if you are a child of the 1970s — about eight out of every 10 birds in the population have disappeared since you rode the bus to elementary school. The loss of olive-sided flycatchers is part of the 3 billion songbirds scientists estimate the world has lost since then.

That steep decline is one of the reasons Hagelin wanted to study olive-sided flycatchers. From 2013 to 2018, she and her intrepid field team tromped into fragrant Alaska swamps of Labrador tea and black spruce trees to capture birds and fit them with geolocator tags. A geolocator weighs as much as a dollar bill, fitted on a bird as light as a stack of 13 pennies.

Because olive-sided flycatchers are so shy around people, Hagelin had to invent ways to capture them. It took much trial and error, including attaching to the spruce tops a 3-D printed decoy of a mock intruder. That plastic male flycatcher was created with the help of Greg Shipman at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute’s machine shop.

Hiding quietly, Hagelin played a recording of “quick, three beers.”

Often, dominant males of the bog would swoop in to oust the trespassing bird, only to be caught in mist nets Hagelin and her helpers had strung in forests near Fairbanks, Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge and Anchorage.

With a good candidate in her hands, Hagelin fit it with a tiny backpack that included a geolocator instrument. That enabled her — upon recapturing the bird the next summer — to determine roughly where it had been during its months away from Alaska.

To her surprise, Alaska birds wintered in Columbia, Ecuador, Peru and western Brazil.

“I knew they flew a long way, but we actually got to quantify how far they go,” Hagelin said. “This is such a big, diverse journey. So many things have to go right. It’s amazing any bird is able to do it.”

She and her coauthors identified 13 “important stopovers,” places where individual birds spent more than a week. In those areas, the birds were probably resting and refueling.

Woodlands of Guatemala and southern Mexico were a favorite of the birds during fall migration. A swath of national forest in northeastern California is important to the birds each spring as they wing their way back to Alaska. The birds also paused in three regions of Central America both when they were leaving Alaska in fall and coming back in spring.

A few other fun discoveries: A male and female mated pair Hagelin captured southeast of Fairbanks returned to the same small patch of Alaska woods again every spring. But the male spent its winter in South America 1,000 miles north of the female.

Once on the wintering grounds in South America, flycatchers do not seem to flit around much.

“One of the birds we monitored didn’t move more than 100 meters for four months of winter,” Hagelin said.

While the Alaska spruce swamps remain safe and ultra-rich in insects — enabling olive-sided flycatchers to breed and hatch nestlings each northern summer — the other stretches of their journey through the Americas are not as dependable.

Deforestation and other degradation of bird habitat along the way have probably decreased the number of olive-sided flycatchers able to make the epic journey back to Alaska and elsewhere in North America.

Hagelin hopes the important migratory spots she and her co-authors identified in their recent paper will help managers along the way protect habitat critical to flycatchers and other declining songbirds.

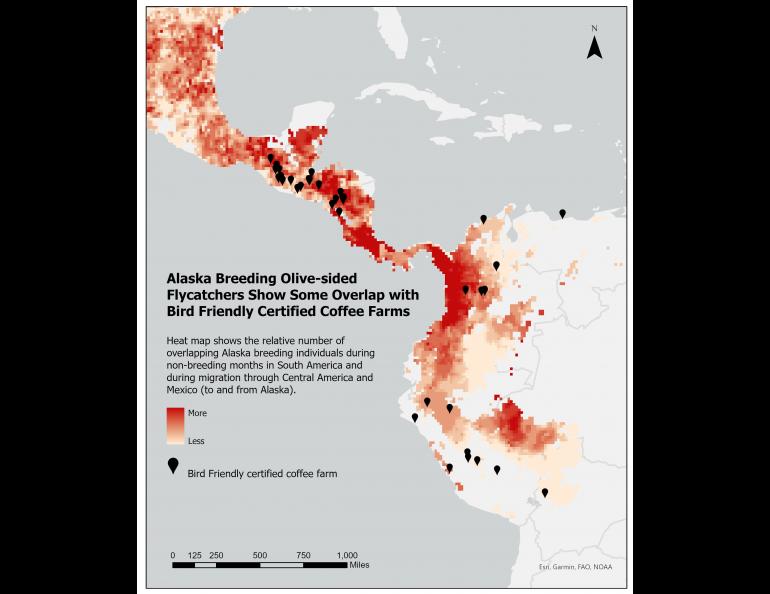

For those who feel a bit helpless but want to help songbirds return to Alaska, Hagelin suggests buying “Bird Friendly Coffee.”

Based on the work of scientists at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, the bird-friendly certification guarantees that coffee comes from farms that provide decent habitat for birds. Farms are required to have at least 40 percent tree-canopy cover and at least 11 tree species, among other requirements.

According to scientists with the Alaska Songbird Institute, three-quarters of the world’s coffee farms are in full sunshine, with producers having cleared out the trees. When the forests disappear, so do migratory songbirds.

Bird-friendly coffee farms feature shady, diverse landscapes preferred by olive-sided flycatchers and many other songbird species that are poised to make the leap toward Alaska soon. Supporting those farms and the companies that roast their beans is a small way to perhaps make a difference, Hagelin said.

“You may be benefiting a bird that passes through your backyard.”