The experiment that never ends

Some experiments never end. Especially ones involving plastic objects released in the far north.

In late July 2011, Paul Boots, a supervisor at an oilfield on Alaska’s North Slope, found a small, yellow plastic disc on a creekbed. Scientists 30 years ago tossed the disc into the sea as part of a study on arctic oil spills.

Boots, who works at the large gravel pad that hosts the Badami oil field, was with his coworkers on an annual cleanup day along a nameless creek just west of the gravel pad.

“I was enjoying a beautiful day and strayed a bit farther than most in my search for ‘fugitive emissions’ (everything we pick up has been blown off of our pad),” he wrote in an email. “I found the disc about 50 yards from the saltwater.”

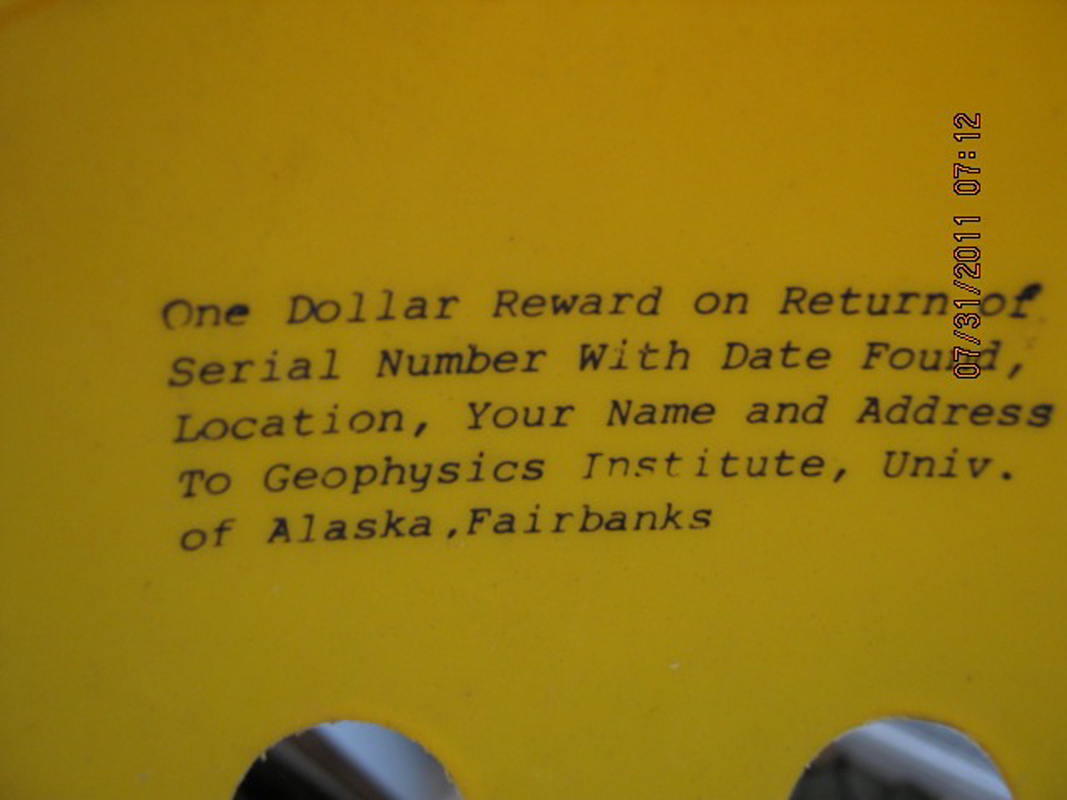

Boots at first thought the saucer was part of a weather balloon. Then he saw a typewritten message: “One Dollar Reward on Return of Serial Number With Date Found, Location, Your Name and Address to Geophysics Institute, Univ. of Alaska, Fairbanks.”

More interested in finding the history of the disc than making a buck, Boots sent a to-whom-it-may-concern message to Blake Moore at the Alaska Climate Research Center at the Geophysical Institute. Knowing I’ve been around here for many moons, Blake forwarded the message to me.

The discs have been subjects of these weekly columns a few times, the first by Larry Gedney in 1982. Gedney wrote of how researcher Brian Matthews and his coworkers released 6,800 of the yellow discs, called drifters, into lagoons and the open sea along the coastline near Prudhoe Bay from 1977 until 1981.

Gedney, one of my favorite writers of this column (which has existed since 1976), described the disc as resembling “a yellow freshman beanie with a two-foot-long flexible stem extending downward from its center.” There were two types of drifter — one that floated on the surface and one with a small brass weight attached to the stem that made it float just below the water’s surface. The stems seem to be the only part of the disc that has disappeared.

People living and working on the North Slope recovered and sent in about 900 of the discs by the time of Gedney’s story, but most of the originals endure somewhere out there. Official monitoring of the experiment ended when Matthews departed from Alaska in the early 1980s, but thanks to the infinite endurance of plastic and the ink message somehow still emblazed on the discs, a few have found their way back to the Geophysical Institute.

In 1998, two brothers beachcombing in northern Scotland found one of the discs and returned it. The disc made it to Scotland after spinning in an ocean current by the North Pole for about a decade before it was spit through Fram Strait, UAF oceanographer Tom Weingartner said at the time. In 2007, a UAF graduate student studying birds on the tundra near Barrow found another one about 60 feet from a lagoon.

At a time when environmental groups are challenging oil companies to prove they can clean up oil spills in the Arctic, a task that is difficult even in settings where oil booms and skimmer boats are on-site, the drifter experiment also points out the remarkable resilience of plastic, a substance that even in its flimsiest form will outlive us all.

This column is provided as a public service by the Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska Fairbanks, in cooperation with the UAF research community. Ned Rozell is a science writer at the institute.