Fairbanks scientists wired into erupting Augustine

A snow-capped mountain 418 miles away has busied up the new year for some Fairbanks scientists.

After working the Martin Luther King Jr. Day weekend, Jon Dehn hurried back into the office Tuesday morning when a seismologist called him to say Augustine Volcano was again rumbling. Dehn drove into work at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The institute is home of the Fairbanks branch of the Alaska Volcano Observatory, a joint program of the United States Geological Survey, the Alaska Division of Geological and Geophysical Surveys and the Geophysical Institute. On his computer, Dehn called up a NOAA weather satellite image that showed a hotspot at the 4,000-foot summit of the cone-shaped volcano. Dehn, a remote-sensing specialist at the volcano observatory, called his AVO colleagues in Anchorage and told them that the satellite, orbiting Earth about 850 miles above the mountain and sending information to a satellite dish at the Geophysical Institute, had confirmed the eruption.

In a different office about 100 yards away, volcano seismologist Steve McNutt spoke to a reporter for CBS news who wanted an image of the volcano, which had just erupted for the ninth time in less than a week. McNutt had driven into work at 4 a.m. twice in the past week because of Augustine. Augustine and many other Alaska volcanoes have seismometers cemented into them that send instantaneous data back to Anchorage and Fairbanks offices of the Alaska Volcano Observatory.

Just down the hall from McNutt, Guy Tytgat looked at his computer and saw that the pressure sensor he had installed on Augustine Island in early January 2006 had endured to record that morning’s eruption. The sensor recorded the drastic change in air pressure from Tuesday morning’s explosive eruption.

Four floors above Tytgat in the Geophysical Institute, Buck Wilson saw the same signal, which took about 40 minutes to travel through the air from Augustine to the UAF campus, where a network of infrasound microphones are spread in the woods. Infrasound waves—generated by explosions, extreme storms, and even the aurora—travel across the globe at frequencies too low for people to hear.

A few floors down from Wilson, another scientist was looking Tuesday to see if Augustine had puffed up. Jeff Freymueller of the Geophysical Institute checked precise GPS receivers installed on the mountain for signs that magma (molten rock within the mountain) was building up within the volcano, causing it to inflate.

The volcano destroyed two GPS stations near its summit, but Freymueller checked the three surviving instruments on Augustine about 10 times on Tuesday, starting when he got out of bed, continuing until he left work, and then once more before he went to bed. He saw no changes; increases of several centimeters in the elevation of the volcano could indicate a big pulse of magma that might precede another large eruption.

Later on Tuesday afternoon, Jon Dehn sipped a Diet Coke after he and colleague Ken Dean sent a map of predicted ash cloud movement to the Air Force Weather Agency in Omaha, Nebraska. On Friday and Saturday, they had tracked six different ash clouds from Augustine.

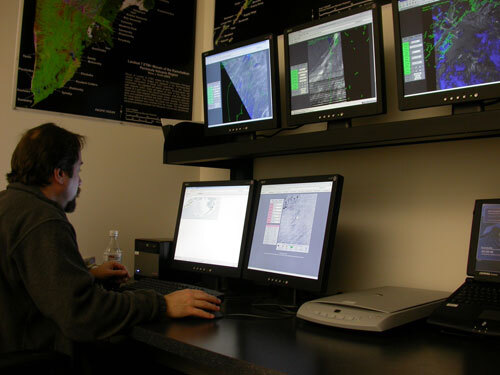

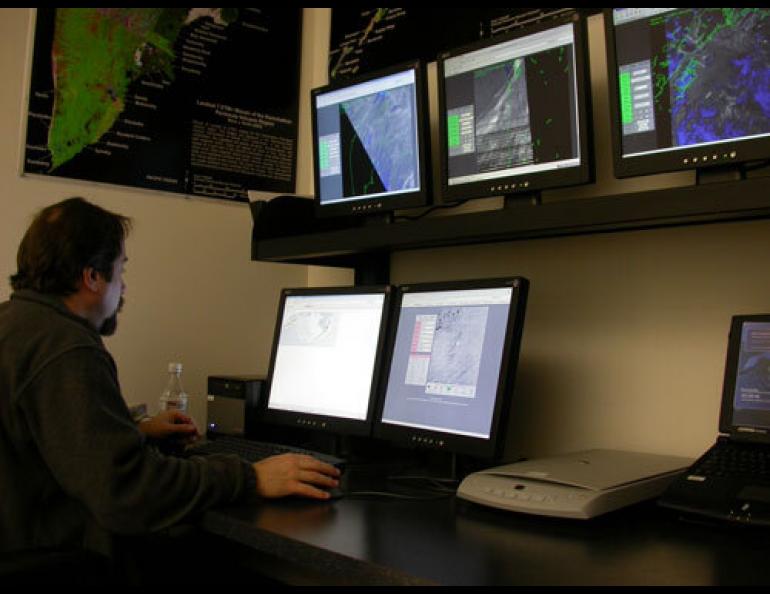

Bleary-eyed after a string of 12-hour days, Dehn walked into a room with 11 full-size computer screens, most with views of the volcano from orbiting satellites. One screen showed icons of planes coming in and out of Anchorage. Earlier Tuesday, Dehn and his colleagues watched that screen as pilots reacted to their predictions of ash cloud movement.

“It’s rewarding when you come in here and watch jets change their course,” he said. “We are the world leader when it comes to this (detailed volcano monitoring). We have to be, because we have so many volcanoes that planes fly over.”