Fingerprinting the waterways of Alaska

CRIPPLE CREEK—With the blackened forest exploding in dust with every step, four scientists hiked to the muskeg bank of this clear-running stream off the Steese Highway with a goal of finding its personality and how fire might have altered it.

Was the stream rich with wriggling larvae that fish prefer, or was it home to fewer insects, possibly a sign of human disturbance? Was the creek flowing cold from the chilled groundwater that fed it, or had the charred tundra warmed it? How much nitrogen and other dissolved nutrients did the water hold?

After a few weeks of hard work in hip boots and time in the lab, the scientists would know a lot more about Cripple Creek, one of 11 Cripple Creeks in Alaska. This one, flowing into the Chatanika River, is part of a larger study on the Tanana River watershed, where scientists are trying to take the chemical, biological, and physical fingerprint of 50 streams to use in future comparisons.

The project is part of a national program of stream monitoring in the western United States. Doug Dasher of the Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation’s Water Quality Division was supervising the sampling of the Tanana watershed streams, hoping to check out 50 of 200 potential waterways in the summers of 2004 and 2005. An active fire season in the Interior had added chaos to Dasher’s schedule, but his stream specialists had by mid-August visited creeks from Manley to the Alaska Range and sampled 28 by the time they reached Cripple Creek. Active fires and dried-up creek beds added to the challenge of the sampling teams, which included students from UAA and UAF.

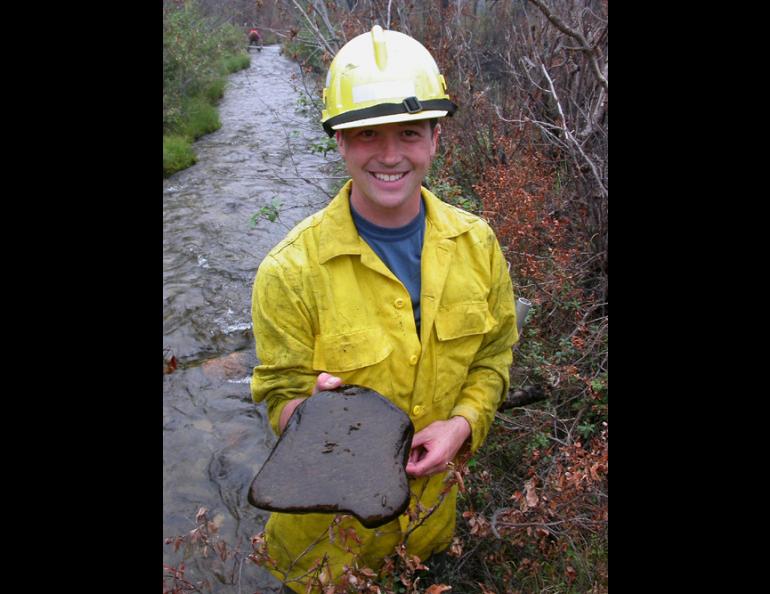

Once they reached Cripple Creek, about 70 miles north of Fairbanks, the four researchers pulled on hip boots and two—Dan Bogan and Mike Booz of the University of Alaska Anchorage’s Environment and Natural Resources Institute— stepped into Cripple Creek and began to find out what sort of waterway it was.

Bogan measured the stream width, the angles of its banks, the percentage of greenery leaning over the creek, the deepest part of the channel, and many more variables. Booz pushed a fine-mesh net to the bottom of the calf-deep creek and kicked at the streambed with his boots, releasing sediment and tiny creatures that he scooped up.

“These guys—stone flies, caddis flies, and mayflies—can be used as indicator species of stream health,” Booz said. “A productive stream will have lots of different species, while less healthy streams might have just midges.”

Why learn all these minute details about a random creek that’s shorter than a 10-K running race? Dasher, the DEC environmental engineer who contracted the UAA scientists to sample the Tanana watershed streams, said the survey of wadeable streams will allow researchers to compare streams’ health now with whatever tomorrow will bring.

“If there was a mine here in the future for example, you would know the background water quality,” Dasher said. “Actual data from Alaska waters can be used to help set the state’s water quality standards.”

Once Cripple Creek has been sampled, researchers can compare its chemistry, biology, and physical characteristics to other creeks of similar size. The program is part of a larger Environmental Protection Agency program designed to “assess the status and trends of national ecological resources.”

The project that included Cripple Creek was a small portion of EPA’s plans for finding out the makeup of Alaska waters. In the next few years, the Alaska DEC hopes to sample the coastal waterways of Southeast, the Aleutians, the Alaska Peninsula, areas that drain into the Bering, Chukchi, and Beaufort seas, the upper Yukon River, and the National Petroleum Reserve on the North Slope.